John Waters: The Musings Interviewby Alison Nastasi

By Yasmina Tawil

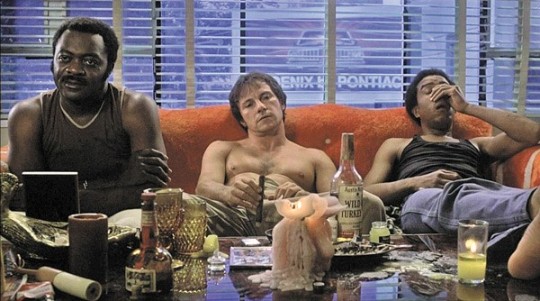

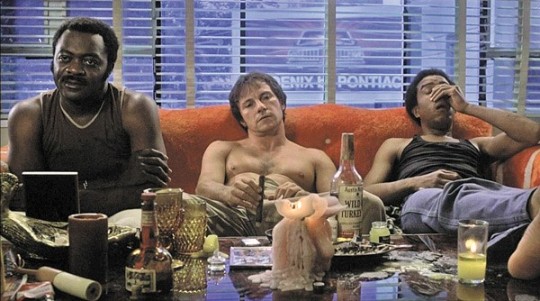

John Waters, the subversive auteur behind the cult films Pink Flamingos and Pecker, watched Ryan Murphys recent anthology TV series Feud every week. The show chronicles the rivalry between screen legends Bette Davis and Joan Crawford during the making of their 1962 film What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? Waters appeared in the shows first season as William Castle, the director of Crawfords B-grade horror movie Strait-Jacket. Decades before Murphy was championing women over 40 in his TV shows, Waters was doing the same for one of the biggest stars of the 1980s. His 1994 suburban-set black comedy Serial Mom cast former blockbuster darling Kathleen Turner in the role of a loving mother who maims and murders anyone who crosses her family. Serial Mom merges Waters trash film roots with Hollywood, poking fun at the middle-class, and the American obsession with true crimewell before the days of popular podcast Serial. Shout Factory recently released a special Blu-ray edition of the film.

Waters fans have been clamoring for a new film since the directors last major feature, 2004s A Dirty Shame. He spends a lot of time writing and reading (Ariel Levys book The Rules Do Not Apply, about her sad miscarriage and breakup of her marriage to a woman and The Son, currently), and hell be hosting an adult summer camp in September. Im writing two books, Im writing a Christmas show, Im promoting my new book, Make Trouble Ive got so many projects I can barely breathe, he told Musings by phone recently. And he doesnt discount the possibility of directing again. I have four development deals… . None of them happened, but who knows? Next time they say yes, Ill do one. Musings revisits Waters serial killer comedy and the Pope of Trashs career for a chat about sex, screenwriting, and suburban malaise.

Musings: Apart from being a great true-crime satire, Serial Mom is an interesting snapshot of the 90s. You reference things like Pee-Wee Hermanthis was during his adult movie theater arrest scandal. Serial Mom was released two months before the O. J. Simpson white Bronco chase. And then Matthew Lillard would star in Scream, the biggest horror movie of the decade, just two years later. This was also when reality TV, talk shows, and court TV were really starting to become popular.

John Waters: I was ahead of my time! I was The Amazing Kreskin!

How much of the movie was informed by that vibe? You dont strike me as a TV junkie.

I never watched any of that. I still dont. A reality show asks you to put people down and feel superior. I dont think Ive done that in any of my movies. I ask you to love my characters, even though others wouldnt.

Whats happened now is that every cable channel seems to be milking the true crime genre to the point that theres nothing new. These documentaries are not documentaries. Theyre just cut and paste jobs of the same thing over and over. They ruined the genre. Truman Capote started it with In Cold Blood, but now there arent many good hardback true crime books to come out that are well written. There are a lot of cheap paperbacks. The shows on TV are pretty bad, too. It seems like every cable station does another miniseries. The older ones were brilliantbut as we all know, whenever anything good happens, they do fifty bad imitations.

I didnt see the new Casey Anthony. I think the Enquirer was a producer. I wrote something once about why I loved the National Enquirer. Well, I hate it nowbecause its just Trump every week. I cant believe anyone is buying the National Enquirer anymore. The headlines arent funny or exciting. Even Trump supporters I cant imagine they would buy it.

Youve said many times that whenever you make a movie about one of your obsessions, like true crime, that its over for you. How do you engage in your obsessions?

Obsessed just means interest to me. I keep reading about it. I keep files about it. Generally, I write about it now. I do a spoken word show all year called This Filthy World. I have a Christmas show that I do in 18 cities in 20 days. I write books all the time. Everything Im interested in, I end up reading it and telling my own stories with it, using it for information in my own work. To me, the newspapers are my soap operas. I look at them every day. Theyre my stories.

I went to so many trials when I was young. I went to Patty Hearst. I went to [Charles] Manson. I went to Hillside Strangler. All those trials kinda showed up in [Serial Mom]. In Pink Flamingoes and Female Trouble theres a trial. Theres a mock trial in Desperate Living. I had those scenes in all my movies. I still think that a really good trial is theater.

Serial Mom and the true crime craze also make me think of how the Satanic Panic spread during the 1980s, and people became obsessed with the gory details of these made-up satanic rituals and abuses in the suburbs.

Oh, so many innocent people some innocent people are still in jail! The Satanic Temple, who I am a supporter ofthough Im certainly not a Satanist they go around the country crashing these conventions of doctors that believe in that stuff and exposing them. It all started with the McMartin case. I went to that trial a lot. They were innocent! Their entire lives were ruined, because of that panic. Im not saying there were never any child molesters in daycare centers, but there were many, many, many who were not.

What was the atmosphere of the McMartin preschool trial?

I went a lot. I had lunch. I sat with the McMartins at the table. I said, Why arent you so angry? They said, Because the lawyer wont let us! They were all found not guilty. The trial lasted forever. People burned down their school. When they sued, I think they only got a dollar once it was over. That poor old lady, Mrs. McMartin they had pictures of her in leather S&M outfits in her wheelchair. They said children were taken away on airplanes. It was all bullshit! The children nicknamed the one accused man Ray Ray [Raymond Buckey, the grandson of school founder Virginia McMartin and son of administrator Peggy McMartin]. That was Johnny Knoxvilles name in A Dirty Shame.

Polyester and Hairspray were made during that time and poke fun at suburban life and the idealism of the 1960s. Does the theres something rotten in the suburbs theme still excite your imagination?

I always make fun of suburbia. Suburbans are always the villains in my movies. I grew up in suburbiaand it was the first thing I tried to escape, so I could go downtown and be a beatnik.

When I hitchhiked across the country, the people picking me up in Mid-America were lovely and great. I dont think its so cut and dry anymore. You can live in suburbia, you can live in the city. Everywhere is cooland there are assholes everywhere, too! You have to weave your way through society no matter where you live and pick and choose carefully.