Monster In A Box: What ‘Wonder Boys’ Says About The Writing Process by Daniel Carlson

By Yasmina Tawil

“A picture used to be a sum of additions. In my case a picture is a sum of destructions. I do a picture—then I destroy it. In the end though, nothing is lost: the red I took away from one place turns up somewhere else.” — Pablo Picasso

///

Writing is boring. Not the act itself—actually doing it can be exhilarating, your head “vibrant with the static of unelaborated thought,” as Philip Roth once described the onset of the creative process. No, it’s watching someone write that’s boring. Next time you see someone in your office crafting an email, look at the way they just kind of stare at nothing for a while, then peck at keys, then shrug and repeat the whole thing before hitting Send and going to the bathroom. It’s always like that. Half of writing is just looking off into space, trying to get ideas to come to you, which is pretty challenging to dramatize on screen. You’re watching someone think, which means you’re trying to watch something invisible.

This is why most movies about writing are actually about typing: a character banging away at a keyboard, usually during a montage, with the finished work appearing as if wished into existence. The actual process of creating—the work of mentally panning through dirt and mud and silt to find jewels worth sharing—is an internal one, which means most films focus on the product, not the process.

Curtis Hanson’s Wonder Boys, though, manages to capture the feeling of the creative process in a way that most movies don’t, and it does so by ingeniously turning that process inside out: instead of a solitary mental experience, it’s an expressive, often public one. Instead of creating silently, we hear people thinking out loud. We get a chance to see people’s creativity fire up because we can actually hear them expressing their thoughts as they come, bouncing from one to another. “Writing” becomes “creating,” and as a result, we’re able to see new things being born, words and ideas breathed into life right in front of us.

///

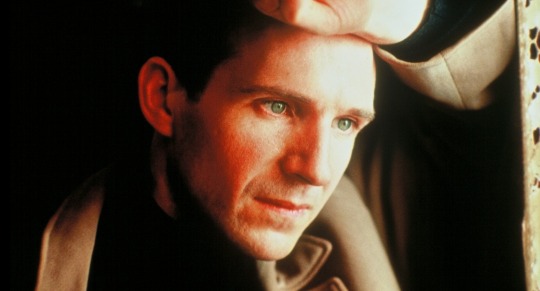

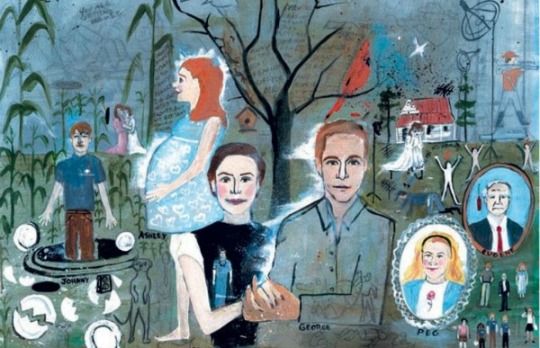

Wonder Boys, directed by Curtis Hanson and released to theaters in February 2000, is based on Michael Chabon’s 1995 novel, which was in turn inspired by the life of novelist Chuck Kinder. Kinder was a professor at the University of Pittsburgh, where Chabon was one of his students, and he was working on a manuscript for a novel that, at one point, stretched to three volumes of 1,000 pages each. That idea—of a writing professor pouring himself into a monster of a book with no end in sight—became the inspiration for Chabon’s character of Grady Tripp, a literature professor who hasn’t published a book in years but who’s working on a massive novel that he can’t seem to corral. Grady, played by Michael Douglas in the film, finds himself at a crossroads as he works on his bloated book, balances his relationship with a married colleague (Frances McDormand), nurtures a pair of students (Tobey Maguire and Katie Holmes), and fends off the predatory capitalistic advances of his agent (Robert Downey Jr.), all while navigating a weekend-long book festival hosted by his university.