The Murder Artist: Alfred Hitchcock At The End Of His Rope by Alice Stoehr

By Yasmina Tawil

“Rope was an interesting technical experiment that I was lucky and happy to be a part of, but I don’t think it was one of Hitchcock’s better films.” So wrote Farley Granger, one of its two stars, in his memoir Include Me Out. The actor was in his early twenties when the Master of Suspense plucked him from Samuel Goldwyn’s roster. He’d star in the first production from the director’s new Transatlantic Pictures as Phillip Morgan, a pianist and co-conspirator in murder. John Dall would play his partner, homicidal mastermind Brandon Shaw. Granger had the stiff pout to Dall’s trembling smirk.

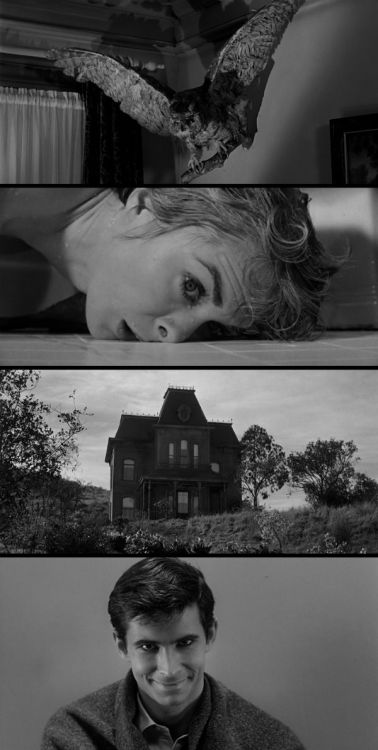

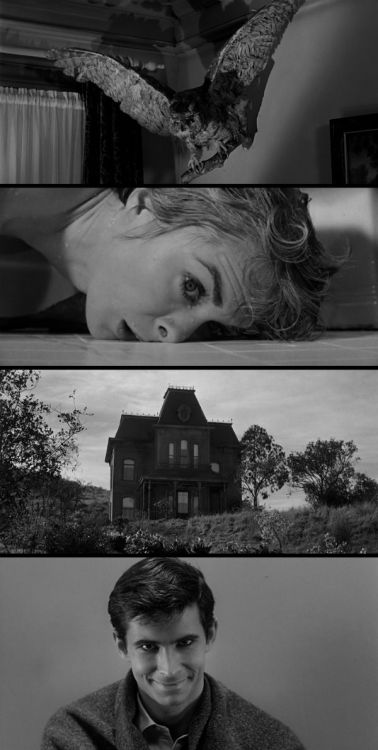

The “interesting technical experiment” was Hitchcock’s decision to shoot the film, adapted from a twenty-year-old English play, as a series of 10-minute shots stitched together into a simulated feature-length take. This allowed him to retain the stage’s spatial and temporal unities while guiding the audience with the camera’s eye. In the process, he’d embed a host of meta-textual and erotic nuances within the sinister mise-en-scène. Screenwriter Arthur Laurents (Granger’s boyfriend, for a time) updated the play’s fictionalized account of Chicagoan thrill killers Leopold and Loeb to a penthouse in late ‘40s Manhattan. There, Phillip strangles the duo’s friend David—his scream behind a curtain opens the film—immediately prior to a dinner party where they’ll serve pâté atop the box that serves as his coffin. It’s a morbid premise for a comedy of manners, and Brandon taunts his guests throughout the evening. (Asked if it’s someone’s birthday, he coyly replies, “It’s, uh, really almost the opposite.”)

Granger deemed the film lesser Hitchcock due to two limitations. One was the sheer repetition and exact blocking demanded by its formal conceit, the other the Production Code’s blanket ban on “sex perversion,” which meant tiptoeing around the fact that Brandon and Phillip—like their real-life inspirations and, to some degree, Rope’s leading men—were gay. That stringent homophobia forced Hitchcock and Laurents to convey their sexuality through ambiguity and implication; the director would use similar tactics to adapt queer writers like Daphne du Maurier and Patricia Highsmith. (“Hitchcock confessed that he actually enjoyed his negotiations with [Code honcho Joseph] Breen,” notes Thomas Doherty in the book Hollywood’s Censor. “The spirited give-and-take, said Hitchcock, possessed all the thrill of competitive horse trading.”) The nature of the characters’ relationship is hardly subtext: Rope starts with their orgasmic shudder over David’s death, then labored panting after which Brandon pulls out a cigarette and lets in some light. A few minutes later, Brandon strokes the neck of a champagne bottle; Phillip asks how he felt during the act, and he gasps “tremendously exhilarated.”

Like Brandon’s hints about the murder, the homosexuality on display is surprisingly explicit if an audience can decode it. The whole film pivots around their partnership, both criminal and domestic. In an impish bit of conflation, their scheme even stands in for “the love that dare not speak its name,” with David’s body acting as a fetish object in a sexual game no one else can perceive. The guests, as Brandon puts it, are “a dull crew,” “those idiots” who include David’s father and aunt, played by London theater veterans Cedric Hardwicke and Constance Collier. Joan Chandler and Douglas Dick, both a couple years into what would be modest careers, play David’s fiancée Janet and her ex Kenneth. Character actress Edith Evanson appears as housekeeper Mrs. Wilson, a prototype for Thelma Ritter’s Stella in Rear Window, and a top-billed James Stewart is Rupert Cadell, who once mentored the murderers in arcane philosophy.