Dallas through the Looking Glass: Post-Truth and Kennedy Assassination Movies by Chris Evangelista

By Yasmina Tawil

Here’s an alarming statistic: a recent CBS News poll revealed 74% of Republican voters believe the conspiracy theory that the offices of Donald Trump were wiretapped during the 2016 presidential campaign, despite there being absolutely no evidence to support that claim. But conspiracy theories are easy to grasp onto. Another poll, this one by Fairleigh Dickinson University, says 63% percent of American voters believe in “at least one political conspiracy theory.” There’s a strange comfort in believing a conspiracy—a sense that you are in the know, while others are on the outside looking in; that you, and a select few others, have discovered the truth, while everyone else is still in the dark.

Conspiracy theories surrounding presidents are nothing new. The wiretapping conspiracy theory, however, had the unlikely distinction of being made popular by the president himself, via Mr. Trump’s serially inaccurate Twitter feed. Trump himself has made his entire political career about conspiracy theories: his current ascendance in the world of politics, for instance, owes something to his leadership of the “Birther” movement—the not-so-thinly veiled racist belief that President Barack Obama is not an American citizen. At the time, Trump and his hateful ilk were on the fringe. Now they’re running the country. Welcome to the post-truth era. Welcome to the world of “alternative facts.”

Shortly after the startling 2016 presidential election, the Oxford Dictionaries selected “post-truth” as the international word of the year. The term is defined as “relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief.” Yet this post-truth way of thinking is nothing new—rather, it has finally gone from existing somewhere on the fringes to playing a role in the mainstream. Perhaps the most overwhelming source of post-truth logic had been in plain sight for the last 53 years, in the conspiracy buff movement that has studied and dissected the November 22, 1963 assassination of President John F. Kennedy. And, as is the case with any event that shocks the world, it was only a matter of time before art attempted to make sense of reality.

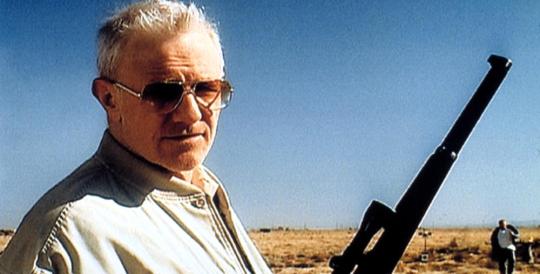

In 1973, ten years after JFK’s assassination, Executive Action found its way into theaters, starring Burt Lancaster, with a script by Dalton Trumbo. Imagine if in 2011 a film about 9/11 being an inside job written by Aaron Sorkin and starring Tom Hanks had been released, and you might have some concept of how startling Executive Action likely seemed. Here was a no-nonsense thriller, inter-spliced with actual newsreel footage of Kennedy, concerning a shadowy cabal of businessmen who make up their minds to murder the president. They have their reasons: Kennedy pulling out of Vietnam will be bad; Kennedy’s support of civil rights will lead to a “black revolution”; Kennedy is taking the country in a distressingly “liberal” direction. What are a group of businessmen, oil tycoons, and ex-US intelligence members to do but put together a very intricate, somewhat convoluted plot to kill JFK and frame a hapless patsy, Lee Harvey Oswald?

Executive Action was the brainchild of attorney and conspiracy buff Mark Lane, who wrote multiple books on the assassination. (Although rumor has it that it was actor Donald Sutherland who came up with the idea first, and tasked Lane with writing a script for him to star in.) Director David Miller’s approach to the script is workmanlike: lots of medium shots, lots of by-the-numbers blocking. No frills. But there is an undeniable effectiveness to the film, mostly in how calmly everything is handled. When you contrast this film with Oliver Stone’s JFK (more on that later), which tells almost the same story, it’s night and day. Stone’s film is frantic, unhinged, to the point that you can almost see the perforations as the film shakes off the reels. Executive Action is cold, businesslike, much like the men who nonchalantly plan to kill the most powerful man in the world. Lancaster, with his clipped cadence, has never been so chilling. He has a simple job—hire men to kill JFK—and he does it the way any everyman might approach a difficult but not impossible task. There’s no drama, no wringing of hands, no moral conundrum. It makes Executive Action all the more believable. Everyone is so calm and collected here that you can’t help but think, “Well, maybe this is how it happened.” (It’s not.)

On the heels of Executive Action came Alan J. Pakula’s darkness-drenched The Parallax View. Parallax isn’t a direct take on the Kennedy assassination, but the implications are unmistakable. Once again, we have a group of shadowy captains of industry pulling the strings behind the scenes. Once again, we have an unfortunate patsy set up to take the fall for a political assassination. Notice a thread here: a lone gunman is framed and blamed. An angry lone nut takes the fall while the real killers go unnoticed, or worse—remain in power, unstoppable. So disillusioned were the American people by both JFK’s death and Watergate that it was easy to believe the forces of darkness were calling the shots.

The bulk of narrative films that address the Kennedy assassination almost all revolve around the assumption that the official story—Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone—was bunk. After all, who was Oswald? A nobody. A scrawny runt with dyslexia. How could one insignificant man alter the course of history? At the same time, why isn’t it more believable that a man with an unstable personality carried out the Kennedy assassination, rather than a multi-tiered, far-reaching conspiracy of shadowy men in smoke-filled rooms? The real Lee Harvey Oswald was a controlling abuser—a man who beat his Russian wife and insisted she never learn English so that he would be her only point of contact in America; a man who resented any and all authority; and a man who, months before the assassination, in April, actually attempted to carry out another assassination of notorious John Birch Society member Major Edwin Walker (an event most conspiracy films never even mention).

If there is one film that conspiracy lore owes the most debt to, it’s Oliver Stone’s 1991 blockbuster JFK. A meticulously crafted, downright brilliant thriller, JFK blends fact and fiction so deftly that one could be forgiven for thinking the film was more of a history lesson than a piece of pop entertainment. Stone, for his part, did very little to clarify what his intentions were. He said in an interview with the New York Times that “every point, every argument, every detail in the movie…has been researched, can be documented, and is justified.” Stone also claimed the film was a “history lesson” and that he was “trying to reshape the world through movies.” Stone also dubbed himself a “cinematic historian” during promotion for the film. Years later, in Matt Zoller Seitz’s expansive The Oliver Stone Experience, Stone had changed his tune slightly: “I don’t call myself a historian. I call myself a dramatist.” In Seitz’s book, Stone seems to downplay the “every detail can be justified” claim and fall back on his speculative fiction angle, although he’s still clearly convinced of a conspiracy.

As a work of fiction, JFK is a masterpiece. Stone, a team of editors, and cinematographer Robert Richardson create an immersive trip through the wild world of JFK conspiracy lore. Stone needed a hero to center the film’s sweaty, paranoid ramblings, and he found it in New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison. As played by Kevin Costner, Stone’s Garrison is a Capra-esque hero, a truth seeker committed to doing the right thing, no matter what the cost. “Let justice be done though the heavens fall!” Garrison trumpets to a team of reporters. JFK has Garrison cracking open the Kennedy case by first looking into the time Lee Harvey Oswald (played with eerie chameleon-like fervor by Gary Oldman) spent in New Orleans, and then cracking open the whole can of worms. Oswald, Garrison learns, is just what he said he was—a patsy. The real killers of Kennedy were the military industrial complex, or maybe the FBI, or maybe the CIA, or maybe the mafia. Or maybe…. well, the list goes on. Despite Stone’s claims at the time of the film being a history lesson, he never presents an entirely concrete connection between any of these conspirators.

The first half of JFK sets up the pieces: here is who may have been involved with the assassination and we’re not sure how all these people fit together, but one thing we know for sure is that Oswald didn’t pull the trigger. The back end of the film turns into a courtroom melodrama, with Garrison bringing local New Orleans businessman Clay Shaw (played with a chilly sophistication by Tommy Lee Jones) to trial for being one of the lead instigators of the assassination plot. Eventually, Shaw is found innocent, and rightfully so—the film presents almost no real evidence to prove Shaw had anything to do with the alleged conspiracy, save for the testimony of a male prostitute, Willie O’Keefe (Kevin Bacon, having the time of his life). Here is where a moral conundrum arises: Clay Shaw was a real person, and really was brought to trial by Garrison. Willie O’Keefe is fictional, a character inspired by a man named Perry Russo. The problem: Russo was so undependable as a witness, his credibility so suspect, and his story so inconsistent, that Stone had to create a fictional character in order to get the story he wanted.

There are more problems with Stone’s approach. The real Jim Garrison was not the crusader for truth the film makes him out to be. The historical Garrison was actually a man who would’ve fit right in with the Trump administration. “Most of the time you marshal the facts, then deduce your theories,” said former First Assistant D.A. and Garrison associate Charles Ward. “But Garrison deduced a theory, then he marshaled his facts. And if the facts didn’t fit he’d say they had been altered by the CIA.” Garrison, for his part, even doubled down on this backwards logic, stating at one point, “The district attorney can make any statements he wishes,” truth be damned. Whatever evidence Garrison lacked, he seems to have fabricated. Most considered his bringing Shaw to trial a miscarriage of justice, and after Shaw was swiftly acquitted, Garrison mostly languished in obscurity. Even the conspiracy buffs distanced themselves from him. Then Stone, and Hollywood, came calling, and Garrison was back in the limelight.

If you’re able to remove the historical elements from JFK, you can easily enjoy it. But when you start to dissect the truth, or at least what’s known of the truth, the waters get murky. JFK’s Oswald is presented as an innocent bystander, unaware of the dark forces working behind the scenes to set him up for the biggest murder in American history. In one wisely deleted scene from the film, Stone even had the ghost of Oswald take the stand during the Shaw trial and flat-out proclaim, “I am innocent!” Vincent Bugliosi’s gargantuan Reclaiming History: The Assassination of President John F. Kennedy is one of the most definitive books written on the Kennedy assassination, and Mr. Bugliosi lays out page after page of evidence that points to Oswald’s guilt—evidence that’s either never touched on or outright altered in Stone’s film. Stone completely ignores the incident where Oswald, using the same gun that was proven to have killed Kennedy, attempted to kill Major Edwin Walker. The film also casually omits the fact that the morning of the assassination, Oswald received a ride to work from a coworker who claimed Oswald had a long, wrapped package with him. Oswald claimed the package was just “some curtain rods”—though why he was bringing curtain rods to work was a mystery. Also a mystery: after Oswald was arrested, he denied bringing any curtain rods. Later, the brown wrapping paper the “curtain rods” were wrapped in was found on the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository, where the shooting allegedly took place. So either Oswald really did bring curtain rods to work, unwrapped them, and then they mysterious vanished, or what he actually had was his rifle. Or perhaps the coworker was lying and in on the conspiracy.

Other casually omitted or altered facts from Stone’s film: during the assassination, a man named Howard Brennan looked up and saw Oswald in a window of the book depository, rifle in hand. Later, as Oswald fled the crime scene, he was believed to have shot and killed Officer J.D. Tippet. Stone’s film presents a scenario in which no one was able to identify Oswald as the shooter of Tippet, when in fact there were ten separate eyewitnesses who placed Oswald at the scene. The list goes on and on. The argument could be made that art has no obligation to the truth. Dramatic license is the bedrock of most biopics and “true story” films. But this is a gray area when it comes to JFK, a film with weighted dialogue like “Fundamentally, people are suckers for the truth. And the truth is on your side.” On top of this, JFK has the distinction of bringing about legislative changes. So popular was Stone’s film that Congress passed the President John F. Kennedy Assassination Records Collection Act of 1992, which established the collection of all U.S. records regarding the Kennedy assassination to be housed in the National Archives. All of this, coupled with the film’s newsreel opening, lends an air of legitimacy to JFK. It turns speculation into perceived truth, intentional or not.

The year following JFK saw the release of Ruby, a film so far removed from historical fact that you’d be hard pressed to find anything true within its plot. Danny Aiello gives Oswald’s killer Jack Ruby a dignity the real Ruby never had, and turns him into something of a folk hero—a man who, like Stone’s Garrison, is committed to doing the right thing. Ruby borders on spy-thriller territory, with Ruby being drafted as a mafia hitman who gets wrapped up in a conspiracy spinning out of control. It’s mostly forgotten, and for good reason. Aside from Aiello’s soulful take on the Dallas nightclub owner, the film is unremarkable. 1993 gave audiences In the Line of Fire, where the Kennedy assassination haunts an aging Secret Service agent (played by Clint Eastwood) who was there that day in Dallas and failed to save Kennedy’s life. In the Line of Fire eschews conspiracy trappings but once again delegates Oswald to a footnote, an afterthought. In the film, a lone nut (played memorably by John Malkovich as something of an inhuman trickster) taunts Eastwood’s Secret Service agent with his plot against the current president via threatening phone calls. “Call me Booth,” Malkovich instructs Eastwood. “Why not Oswald?” Eastwood asks. “Because Booth had flair, panache,” replies Malkovich. “A leap to the stage after he shot Lincoln.” Oswald just isn’t dramatic enough for this assassin to emulate—and then again, maybe he was innocent?

2002’s Interview With the Assassin is an unjustly overlooked, highly creative take on conspiracy lore. Told in faux documentary style, the film follows an amateur filmmaker (Dylan Haggerty) approached by his elderly next door neighbor (a creepy yet hilarious Raymond J. Barry). The neighbor has a story to tell: it was he, not Lee Harvey Oswald, who delivered the fatal JFK head shot. As the filmmaker follows the alleged assassin, he first comes to believe the man’s story, then begins to have his doubts, convinced that the neighbor is just a deranged nut, before coming back around to belief for the film’s conclusion, all while the specters of shadowy government agents lurk in the background. Again, just as Executive Action and JFK deployed documentary-style footage to lend an air of legitimacy to their narratives, Interview with the Assassin is deceptively plausible. In fact, if you were unfamiliar with Raymond J. Barry, a great character actor with 114 screen credits to his name, you might actually fall into the Blair Witch Project trap and believe this really is a documentary, so believable and convincing is Barry’s performance.

As the 21st century progressed, the filmic approach to the Kennedy assassination shifted. Conspiracy began to take a back seat to attempts at “setting the record straight.” Perhaps in the specter of 9/11, with its “inside job” nuts coming out of the woodwork to proclaim, “Jet fuel doesn’t melt steel beams!”, or in light of the deplorable “Sandy Hook truthers,” who have the unmitigated gall to claim the murder of 20 children was a “false flag,” Hollywood has lost its taste for propping up conspiracies. 2013’s Parkland told a Short Cuts-like story of the minutes and hours following the assassination: From the team of doctors who valiantly but fruitlessly tried to save JFK’s life to a befuddled Abraham Zapruder (Paul Giamatti) coming to terms with the fact that by filming the head shot he’s now in possession of the most important “home movie” in history to Robert Oswald (James Badge Dale), whose entire life is suddenly upended by his estranged brother Lee (Jeremy Strong). Parkland doesn’t delve into the investigation, but makes it clear it believes Oswald is the sole killer. The film is curiously flat, failing to hit any of the big emotional beats it strives for. Where it succeeds is in taking the time to show the blood and confusion inside the Parkland hospital emergency room, and it does highlight the surreal occurrence of Oswald being wheeled into the same hospital with his own fatal wound so soon after the assassination.

Oddly, the most historically accurate portrayal of the assassination, and the events leading up to it, can be found in a work of science fiction. The Hulu mini-series adaptation of Stephen King’s 11.22.63 draws on King’s meticulous research into Oswald, and shows Oswald’s tumultuous, abusive marriage as well as his failed assassination attempt on Edwin Walker. It also shows him pulling the trigger. The twist in this whole narrative is that this is a time travel story, about a 21st century English teacher (James Franco) who goes back in time to try to stop Oswald. Franco’s character can only travel to 1960, and thus has to wait it out till 1963. He can’t just outright kill Oswald, though, because the doubt remains: what if Oswald really is innocent? As a result, 11.22.63 becomes a detective story, with Franco’s time traveller trying to piece together evidence to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Oswald really is going to kill JFK, and then stop him. Of all the JFK films, 11.22.63 is the first to truly represent how unpleasant and abusive Lee Harvey Oswald was. As played by Daniel Webber, Oswald is a cruel jerk with delusions of grandeur, convinced he’s destined for greater things if only everyone would just get out of his way. This is closest to the real Oswald, based on the testimony of those who knew him, including his wife Marina. At one point, the real Oswald even boasted that one day he’d obtain the non-existent office of “Prime Minister of America.” The Oswald in 11.22.63 is an entirely different species than the sainted black-and-white ghost who takes the stand in JFK and proclaims his innocence.

Pablo Larraín’s recent Jackie took the assassination narrative further than any film before it by dealing directly with the effect it had on both the nation and Kennedy’s widow (Natalie Portman). Jackie is obsessed with myth making, and much like the myths and conspiracies that sprung up in the years following JFK’s death, the film is awash in events that bend the truth and stagger the mind. A numbing effect sets in, as grief gives way to acceptance and some attempt at understanding. As doctors perform an autopsy on her husband at Bethesda Naval Hospital, Jackie, her pink dress stained with blood and gore, paces around the emergency room in a fury. “It had to be some silly little communist,” she spits as word of Oswald’s arrest for the murder spreads. “If [Jack had] been killed for civil rights, at least then it would have meant something, you know?” This line of dialogue from Noah Oppenheim’s script gets to the heart of the conspiracy movement: perhaps if the reasoning behind Kennedy’s murder had been some grander scheme instead of the actions of a lone gunman grasping at fame, then maybe there would be more meaning behind all of this. Maybe then life wouldn’t be so arbitrary, so random.

Jackie plans her husband’s funeral as pageantry; it’s not just a somber service, it’s a Hollywood remake of Abraham Lincoln’s funeral, with a march through wintry streets as all the world is watching. Following the funeral, she tells her story to a reporter (Billy Crudup), but she dictates the direction the story goes. She wants final approval over his story, and forbids him from writing up certain elements—like the fact that she smokes. “I’m just trying to get to the truth,” Crudup’s reporter says. “The truth?” Jackie replies. “Well I’ve grown accustomed to a great divide between what people believe and what I know to be real.” “Fine,” says the reporter. “I’ll settle for a story that’s believable.”

So must we all, especially here in whatever post-truth reality we find ourselves stuck in. The problems begin when we decide to pick and choose what it is we consider “believable,” and who we believe. “People like to believe in fairytales,” Portman’s shell-shocked Jackie tells us. Before the 2016 presidential election, one could safely argue the case for eschewing truth for the sake of art. Now, things might not be so simple. A decisive lack of truth unquestionably contributed to our current situation, just as a decisive lack of truth is integral to the bulk of the films that attempt to dissect the JFK assassination. In these films, the truth is what we make of it. Some may find comfort in that, but these days, the implications are terrifying.