The Arc Of Stanley Kubrick: From Killers Kiss to Eyes Wide Shutby Noel Murray

By Yasmina Tawil

Stanley Kubrick made just 13 feature films in his nearly 50-year career, and from the ‘60s through the ‘90s—the era in which “a Stanley Kubrick picture” had a meaning—each new project went through more or less the same press-cycle. During production, reports would leak out about the grueling shoot, and how the reclusive Kubrick was testing the boundaries of cinema and propriety. Then the film would come out, and the critical reaction would be mixed to muted, with some declaring the new work a masterpiece and others calling it a disappointment—or even a pretentious fraud. Years would pass, and with time to sink in, each movie would be extensively reevaluated, eventually landing on “best of the decade” or even “best of all time” lists. It was as though each picture had to re-teach the audience how to watch a Stanley Kubrick film.

Eyes Wide Shut is the best case-in-point. Shooting began in the November of 1996 in London, and ended in June of 1998. Throughout that year and a half, there was gossip galore about what Kubrick was up to. The press knew primarily that the film starred Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman—Hollywood’s most popular couple at the time—and that it was going to be sexually explicit. Once filming completed, Kubrick spent nine months working with editor Nigel Galt, fine-tuning. Less than a week after he completed a final cut and showed it to Warner Bros. and his stars, he died.

So when the movie came out that summer, for a good long while the conversation surrounding it was about everything but what Kubrick had actually made. Instead, the press was preoccupied by…

… the decision to digitally obscure the orgy scenes, to avoid an NC-17 rating.

… whether Cruise and Kidman had wasted a year of their careers making stilted softcore porn.

… how American audiences reacted to seeing two of the biggest movie stars in the world in a slow-paced art-film.

… whether the Pinewood Studios version of Manhattan looked real enough.

… whether Warner Bros. was going to make its money back.

… if this was the proper capper to a prestigious career.

By the end of 1999 though, a film that had generally been tagged as a “letdown” was being rehabilitated. Roger Ebert taped a special edition of his syndicated TV series, wherein prominent Chicago critics extensively unpacked Eyes Wide Shut—and thus subtly rebuked the large number of well-known New York critics who’d initially shrugged the movie off. The film made a healthy handful of best-of-‘99 lists (including in New York), and in the decades since it’s generally become regarded as one of the ‘90s supreme cinematic achievements, and indisputably worthy of its maker.

Most of the shift in conventional wisdom was due to Kubrick himself. When artists produce outstanding work throughout their careers, it’s easier to trust that they knows what they’re doing—and that if we don’t “get it” right away, we should look again. It’s also true that once a film is out of the multiplex marketplace, questions like, “Did you like it?” become less pressing. Opinion takes a backseat to analysis. And with Eyes Wide Shut, there’s as much to pick through and puzzle over as in any of Kubrick’s films—even though almost nothing that happens in the picture is left unexplained.

Based on Arthur Schnitzler’s Traumnovelle, the movie has Tom Cruise playing Dr. Bill Harford, a successful New York general practitioner who lives in a lavish apartment with wife Alice (Kidman) and their young daughter. The story begins with the couple going to a lavish Christmas party thrown by Bill’s patient Victor Ziegler (Sydney Pollack), where the pair flirts with other guests before the doctor’s called in by his host to attend to a nude, overdosing woman. The next night, Bill and Alice have a testy argument about sexual desire, during which Alice confesses that she’s recently lusted after another man. Still fuming, he leaves the apartment to go on a house call, and begins a winding two-day odyssey that sees him sexually tempted multiple times. A combination of desperate arousal and burning envy nearly puts him in mortal danger, after he crashes a bizarre masquerade party at a country estate.

For a long time, Bill’s journey into the night feels like an erotic dream that keeps threatening to become a nightmare. (In fact, Traumnovelle is sometimes translated in English as A Dream Novel or Dream Story.) But at the end, Bill meets again with Victor, who offers a different interpretation of the previous 48 hours. Bill’s anxious because the morning after he was ejected from the masquerade, one of his friends went missing and a woman who helped him turned up dead. Victor insists that the friend just left town, the woman was a junkie prostitute, and the masked men at the party weren’t really threatening Bill, they were maintaining the theatrical illusion of an event meant to resemble a decadent, dangerous gathering of some ancient clandestine tribunal.

Victor could be lying. Or more likely he’s acting as Kubrick’s surrogate, telling the audience not to think too hard about shadowy cabals and unsolved murders, because that’s not really what Eyes Wide Shut is about.

For those who prefer to focus only on plot, Eyes Wide Shut is the story of a couple who live comfortably, but only because they offer something of value to those even richer than themselves. Bill’s most embarrassing experience at the masquerade is his discovery that even when he knows the right people, he’s not really in their league. Alice, meanwhile, in one of her few big scenes, admits to a lecherous older man that she’s out of work, as he paws at her and makes promises to reintroduce her to the art world.

According to Kubrick’s closest confidantes though, the real reason he wanted to make Eyes Wide Shut wasn’t to explore class, but to scrutinize marriage. That may seem dubious, given how little screen-time Bill and Alice share. But as far back as the early ‘60s—when he was making his frustratingly neutered version of Nabokov’s Lolita—Kubrick reportedly talked about making a movie that dealt frankly with sex in the context of a committed relationship. The mysteries of married life are mostly covered in one scene, when Alice admits that she feels closest to Bill when she’s attracted to other guys. Her argument makes a perverse sense, but the thought that she lusts after strangers but comes home to him doesn’t comfort Bill, who’s so haunted by her confession that he immediately goes out and spends two days trying (and failing) to have sex with anyone, anywhere. He becomes every husband who’s ever been told “not tonight honey” and then spent the weekend acting really pissy about it.

Critics and audiences in the summer of 1999 didn’t miss any of Eyes Wide Shut’s underlying themes, because again, Kubrick made them pretty plain. The question instead was whether he needed to spend two-and-a-half hours on something so seemingly slight, with performances so… spacey. Whenever Kubrick gets tagged as “detached,” “chilly,” or even “misanthropic,” it’s usually because of his preferred style of acting. His characters tend either to over-emote (like Jack Nicholson in The Shining or R. Lee Ermey in Full Metal Jacket) or speak slowly and flatly (like everybody in 2001 and Barry Lyndon). Kubrick also likes to break up the lines of dialogue with long pauses, which slows the pace further and makes reactions seem less natural. Viewers who dislike Eyes Wide Shut—which included the large numbers of 1999 cinema-goers who lined up to see two movie stars get naked—often trash the performances as “bad.” But it takes a lot of skill to maintain poise and charisma while the director’s shouting, “Do it again, but slower.”

***

The discord between the affectless and the over-the-top in Kubrick’s films dates all the way back to his earliest work—though in the likes of Paths Of Glory, the artificiality was disguised by an overall swiftness of pace that Kubrick would later eschew. There was a gradual evolution to the director’s style. What unites Kubrick’s awkward early independent films and his later big-budget studio work is a sophistication and worldliness, far removed from the palliative approach of other movies from their era. As a young filmmaker he’d treat each shot and each scene as a unique creative exercise, in effort to make audiences say, “Well, that’s new.” Early on he wove his preferred stylized acting into images that were strikingly lit but otherwise steeped in photographic realism. Meanwhile, his scripts that make liberal use of narration and time-jumps, suggesting fresh, inventive ways of telling stories through cinema.

Kubrick became a filmmaker as an extension of his day job as a Look magazine photographer. He taught himself how to operate a cheap movie camera in his early 20s, so that he could make some money from a newsreel company that needed shutterbugs. Building off of that experience, Kubrick made the hourlong 1952 fiction feature Fear And Desire, with his family’s money. Though the ultra-low-budget war movie is so ponderous and clumsy that the director later disowned it, it showed enough promise to impress a few critics and get limited theatrical distribution in 1953—rare for an indie. So Kubrick reunited with his Fear And Desire screenwriter, future Pulitzer Prize winner Howard Sackler, to make 1955’s Killer’s Kiss. Kubrick’s second feature film is less of a grand statement on human existence and more of an attempt to show off his eye.

Killer’s Kiss has barely any story. Jamie Smith plays Davey Gordon, a boxer on his last legs, while Irene Kane is Gloria Price, a dancer-for-hire who lives in the apartment across from his window. Like Robert Wise’s classic 1949 noir The Set-Up, Kubrick and Sackler’s peek at urban squalor uses the fighter and the hoofer’s separate preparations for their jobs as an way of exposing city life at its most sweaty, exhausting, and lurid. Then Gloria gets harassed by a mob-connected thug, and when Davey intervenes, Killer’s Kiss turns into a minor-key romance, broken up by long chase scenes. Almost the entire last 20 minutes consists of shots of people on the run, strikingly framed atop and betwixt towering skyscrapers.

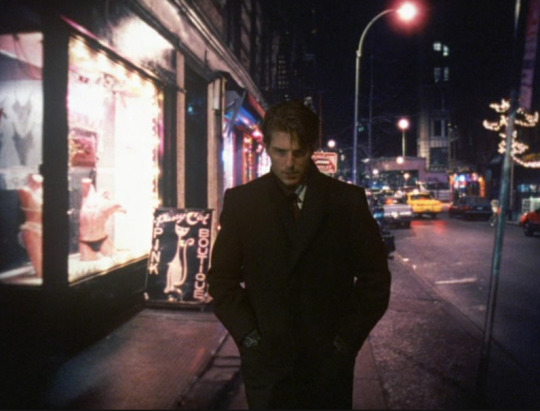

On the Criterion Collection Blu-ray of the 1956 thriller The Killing (which contains the entirety of Killer’s Kiss as a bonus feature), critic Geoffrey O’Brien narrates a video-essay about Kubrick’s second film, praising its “tremendous sense of possibility” and its “made up as it goes along quality.” What he’s mainly referring to is how much of the 67-minute running time is dedicated to simple, docu-style New York street scenes. Unlike the studio-shot artificiality of Eyes Wide Shut’s NYC—which was so phony that residents of the city, critics included, griped about all the geographic and architectural inaccuracies—the New York of Killer’s Kiss is almost frighteningly real, depicting a metropolis always teetering on the edge of mayhem. O’Brien and other critics have compared Kubrick’s cinematography to the stark crime-scene photographs of Arthur “Weegee” Fellig.

That shouldn’t be surprising, given Kubrick’s past. He started filing photo essays for Look as a teenager, after catching the magazine’s attention with a staged photograph of a New York news vendor reacting to Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s death. As a photographer, he specialized in mocked-up scenes of city life, from paddy wagons to college campuses, all viewed from skewed and cynical perspectives. He frequently arranged his subjects in series of shots to create a narrative—often steeped in irony—but because he couldn’t control the environment, the snaps contain a lot of spontaneity.

Kubrick brings those gifts to Killer’s Kiss, particularly in the scenes that take place in Davey’s apartment, where he peers into a tiny fishbowl while the tight spaces and big open windows behind him reveal him as his own kind of animal trapped behind glass. Killer’s Kiss features a number of standout visual experiments: a graceful ballet sequence; a boxing match playing out in quick cuts (with views from the canvas and the ropes); a nightmare sequence constructed from polarized footage; a special effect that makes the screen look cracked after someone throws a glass toward the camera; a fight in a mannequin warehouse; and an over-the-top corny “letter from home” from the rural northwest, heard in voiceover while the hero rides in a grubby subway car. But what’s most impressive is that—over three decades before Eyes Wide Shut—Kubrick tours through a New York where characters feel like they’re on display, and where they can’t disguise their base desires.

***

By the time Kubrick crossed over to the mainstream with the tough, taut genre pieces The Killing and Paths Of Glory, he’d acquired a distinctive style and tone: a sort of detached disgust. But in all the conversations about Kubrick’s technical mastery and bleak vision of humankind, what often gets missed is that the man had a mischievous wit. He was known to have late-night transatlantic phone calls with his American friends and colleagues where he’d gush enthusiastically about his favorite TV sitcoms and movie comedies. Dr. Strangelove is his most overtly comic picture, but there’s a strong element of wry humor in nearly all of his films, even if it’s just in the contrast between the pretensions of high society and its baser impulses. That’s evident throughout Barry Lyndon, for example, where all the powdered wigs and finery can’t cover up the characters’ greed and cowardice.

Tom Cruise has rarely gotten enough credit for how funny he is in Eyes Wide Shut as Dr. Bill: an earnest man accustomed to winning friends and clients with his skill for saying exactly the right bland, inoffensive thing at the right time. As he investigates the sexual underground of New York—flashing his medical certification like a police detective’s badge—he becomes increasingly pathetic, and comic. Eyes Wide Shut is especially perverse in the way Kubrick keeps undercutting the eroticism and elegance. The film opens with a shot of Alice’s bare backside, then a few minutes later shows her sitting on a toilet. Later, when Bill gets lured by what appears to be a high-class hooker, he steps into an apartment cluttered with dirty dishes and drying laundry. The women in Eyes Wide Shut are impeccably made up and coiffed, but Kubrick subverts the “painted doll” effect by adding a pair of glasses, or putting them in unflattering nude poses. If the movie has one keystone shot, it may be the seemingly random cut back to Alice sitting in her kitchen eating Snackwell cookies while Bill’s out testing his manhood.

That fascination with minutiae ultimately is the best rebuke to the notion that Kubrick sneers at humanity. Again and again in his films the characters are seen in small moments where their guard is down and they’re being endearingly human. Almost as much as its magnificently choreographed battlefield scenes and dark ironies, Paths Of Glory is a masterpiece because of scenes like the one where two French soldiers talk about how they’d prefer to die—sounding like a couple of caffeinated dudes in a dorm, not warriors on the frontline. In Eyes Wide Shut, while Kubrick’s orchestrated gliding camera moves through Bill and Alice’s apartment, he has the two of them talking about the name of the babysitter, and saying that they’ll hold their cab for her when they get home from Victor’s party.

It’d be wrong to say that characters in Kubrick films talk like regular people talk. But they are often preoccupied with the mundane in ways that are conspicuous, given how deep and heavy his movies are so much of the time. The filmmaker may have been short on faith in mankind, but he loved and understood his fellow homo sapiens in his own weird way.

So why did it always seem to take so long for even Kubrick fans to unpack everything his movies had to offer… including the humor, and the subtle empathy? Blame—or credit—his dense and imposing style, which was often the only thing critics could notice about his work on first viewing. It’s much easier to appreciate what’s happening in Killer’s Kiss, where Davey in voice-over openly admits to being turned on by how Gloria is “all smiles and yawns” when she invites him in for breakfast. The fumbling, the fawning, the fear… it’s all right there on the surface in Kubrick’s earliest films. His vision of the world didn’t change much between the early ‘50s and the late ‘90s. He just started wrapping it in layers.