We Used to Believe: Fantasies of Institutional Democracy in 1960s Hollywood by Steven Goldman

By Yasmina Tawil

During the last months of his life, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt ordered that the mantelpiece in the White Houses state dining room be inscribed with John Adams prayer: I pray Heaven to bestow the best of Blessings on this House and on all that shall hereafter inhabit it. May none but honest and wise Men ever rule under this roof.

Adams, the second president but the first to inhabit the Executive Mansion, as the White House was more often called in those days, couldnt have known how much urgency we might attach to such a prayer in an age of terrorism, global warming, and nuclear weapons. Nor could he have anticipated the way that the passage of time might alter and sometimes outright distort our perception of presidential honesty and wisdom; our definitions of both might be radically different from his. Our films on presidential politics are a snapshot of our hopes and fears, a way to work out our anxieties through fiction. Two films that emerged in reaction to the election of 1960, Advise & Consent directed by Otto Preminger, and The Best Man, written by Gore Vidal, reflect those anxieties as acutely as any ever made.

Like Freuds cigar, sometimes a film is just a film, of course, and not every presidential portrayal on celluloid betrays a hidden wish or worrymaybe Bill Pullmans fighter-flying Thomas Whitmore in Independence Day (1996) or Harrison Fords combat-veteran James Marshall in Air Force One (1997)both chief executives who take matters into their own handshave a subtext in partisan gridlock during the Clinton years, but more likely theyre just action heroes going with the flow in outlandish films. Sometimes, though, the relationship is on the nose, such as in the 1933 fascist fantasy Gabriel Over the White House, which appeared at roughly the nadir of the Great Depression. Walter Huston plays a lackadaisical playboy president who suffers a near-fatal accident and is reborn as a Mussolini-like figure who solves the countrys problems through sheer force of will (and guns). At about the same time, there was also The Phantom President, a Rodgers and Hart musical, in which no less than the Yankee Doodle Dandy himself, George M. Cohan, reminds convention delegates about to nominate him for president:

My friends, this land is sad today,

It faces want and dearth.

But government of the people,

By the people, for the people,

Shall not perish from the earth.

The chorus answers, Hey, hey, heythats a new thought.

On the calmer end of the spectrum, at a time when Roosevelt was saying he was less concerned with being a great president than with not being the last president, the years 1930-1940 brought no less than three major films about Abraham Lincoln (D.W. Griffiths Abraham Lincoln, starring Walter Huston; John Fords Young Mr. Lincoln, with Henry Fonda portraying Lincoln as lawyer; and John Cromwells Abe Lincoln in Illinois, with Raymond Massey as the titular character) each bearing the reassuring message that when the Republic was last under threat, a hero arose to restore order.

The United States was a far more stable and prosperous proposition during the 1960 presidential campaign season, but the choice between Democratic Senator John F. Kennedy and incumbent Vice-President Richard M. Nixon made it a change election nonetheless. The previous three presidents had been born between 1882 and 1890. Kennedy, 43 years old, or Nixon, 47, would be the first president in United States history born in the 20th century. Whether one agreed or disagreed with the policies of Roosevelt, Harry Truman, or Dwight Eisenhower, in a very real sense the reassuring grandpas who had steered America through the frightening progression of the Depression, World War II, and the Cold War were going away for good.

There were good reasons to doubt both men. If Kennedy won, he would be the youngest elected president in history. While his panache made an appealing contrast with the dowdy Eisenhower, it was also a reminder that he was inexperienced, with an indifferent record in the Senate. Old New Deal Democrats, including Eleanor Roosevelt, doubted Kennedys bona fides. As Arthur Schlesinger Jr. put it, Kennedy seemed too cool and ambitious, too bored by the conditional reflexes of stereotyped liberalism, too much a young man in a hurry. He did not respond in anticipated ways and phrases and wore no liberal heart on his leave. In particular, the Kennedys had failed to repudiate the Red-baiting demagoguery of Senator Joe McCarthy and had, in fact, supported him.

Kennedy was also burdened by inherited doubts. He was a Catholic, and anti-Catholic prejudice was still strong in the country; it had helped defeat Democrat Al Smith in the election of 1928. There was also the looming presence of his father, Joseph Kennedy, a wealthy, unscrupulous climber who had sunk his own presidential ambitions by advising appeasement of Hitler while serving as ambassador to Great Britain at the outset of World War II.

As a Congressman, Senator, and Vice-President who had successfully debated Nikita Khrushchev and stepped in as pinch-president when Eisenhower was ill, Nixon had experience in spades, not that the old general acknowledged it. (Asked at a press conference to name an example of a major idea of [Nixons] that you had adopted, the president replied, If you give me a week, I might think of one. I dont remember.) That experience, though, contained a fair share of disqualifiers. He had pioneered McCarthys tactics, first in his campaigns for the House and Senate, then in the divisive Alger Hiss affair. Due to the revelation of a campaign slush fund, which he combated with the infamous Checkers speech, he seemed to many not just an unscrupulous careerist, but also an example of tawdry, down-market venality. No class, was Kennedys two-word dismissal, an assessment that was echoed in campaign signs that asked, Would you buy a used car from this man? Anticipating Donald Trump, Nixon had tried to rebrand himself so often that one commentator said the question was not if there was a new Nixon or an old Nixon, but whether there is anything that be called the real Nixon, new or old. (James T. Patterson, Grand Expectations, 435.)

Tensions around the election were unsurprisingly stoked by the candidates. Kennedys major theme was the anodyne, Its time for America to get moving again, but in his first televised debate with Nixon, he began by questioning, Lincoln-style, whether the world could continue to exist half slave and half free, asking, Can freedom be maintained under the most severe attack it has ever known? It was as if the Russians were about to march down Pennsylvania Avenue and paint the White House red.

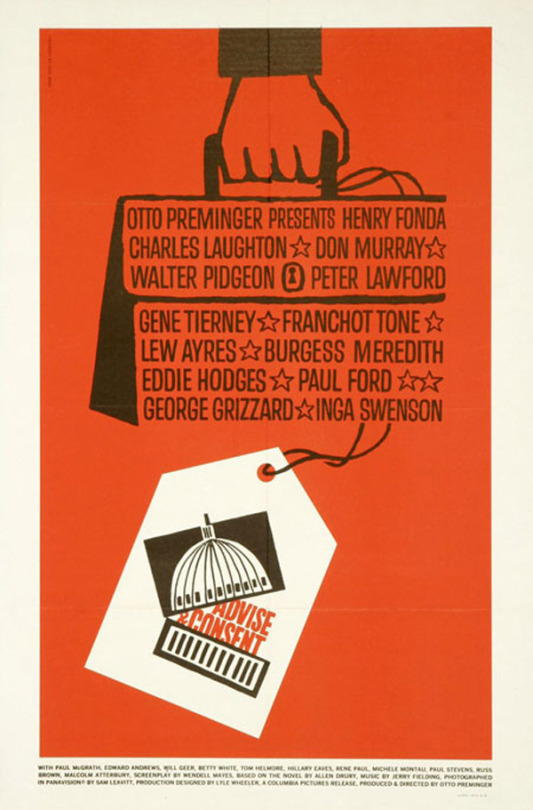

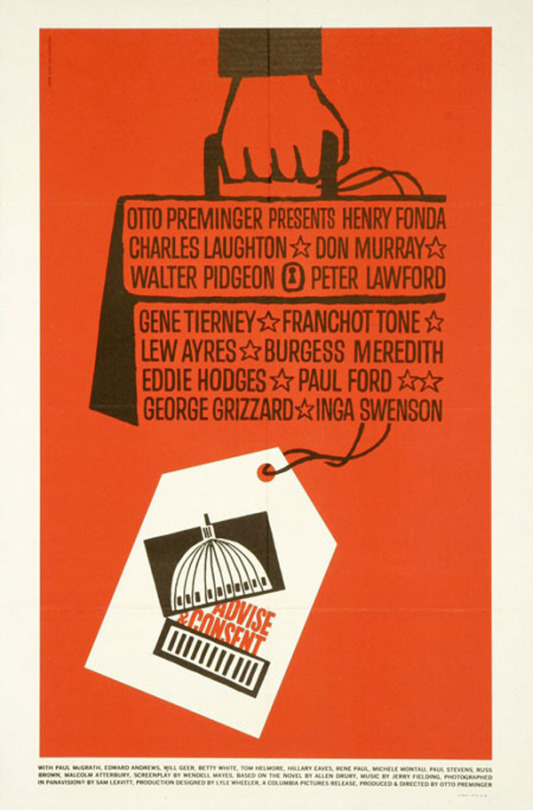

Unsurprisingly, with the old guard fading away and the new guard doing what it could to shatter any sense of serenity, public uncertainty about the election expressed itself in polemical art that asked tough questions about the integrity of the American political system and the quality of men that system produces. Among the first was the novel Advise and Consent by Allen Drury, appearing in 1959. A huge bestseller and inexplicable winner of the Pulitzer Prize, it became a Broadway play the next year, with the film version, directed by Preminger, finished in time for Oscar season in 1961 but held back for contractual reasons until June 1962. Vidals play The Best Man premiered on Broadway on March 31, 1960. The film adaptation, directed by Franklin Schaffner (who had directed the Broadway version of Advise) appeared on April 5, 1964. Significantly, both struggle to find an ending that does not duck the questions the stories pose, and both fail. Over 50 years later, with a presidential election of our own in the offing, we are still asking the questions.

*

In Advise & Consent, an unnamed, ailing president (Franchot Tone) nominates controversial candidate Robert Leffingwell (Henry Fonda) to succeed the recently deceased Secretary of State. Leffingwell is an intellectual who disdains kneejerk anti-Soviet policies. The former head of two federal agencies, he has made powerful enemies among the senators who must confirm his appointment, chief among them senior senator from South Carolina Seab Cooley (Charles Laughton, visibly ailing in his final role). Leffingwell also has an obsessive advocate in the sneering, peace-at-any-price junior senator from Wyoming, Fred Van Ackerman (George Grizzard). Caught between them is Brigham Anderson (Don Murray), senior senator from Utah, who will chair the subcommittee assigned to conduct the confirmation hearings. A family man with a pretty wife and a young daughter, Anderson is hiding a secret that could influence his vote if one side or the other was to get ahold of it.