The Pixelated Splendor of Michael Manns Blackhatby Bilge Ebiri

By Yasmina Tawil

[Last year, Musings paid homage to Produced and Abandoned: The Best Films Youve Never Seen, a review anthology from the National Society of Film Critics that championed studio orphans from the 70s and 80s. In the days before the Internet, young cinephiles like myself relied on reference books and anthologies to lead us to films we might not have discovered otherwise. Released in 1990, Produced and Abandoned was a foundational piece of work, introducing me to such wonders as Cutters Way, Lost in America, High Tide, Choose Me, Housekeeping, and Fat City. (You can find the full list of entries here.) Our first round of Produced and Abandoned essays included Angelica Jade Bastin on By the Sea, Mike DAngelo on The Counselor, Judy Berman on Velvet Goldmine, and Keith Phipps on O.C. and Stiggs. Over the next four weeks, Musings will continue with another round of essays about tarnished gems, in the hope theyll get a second look. Or, more likely, a first. Scott Tobias, editor.]

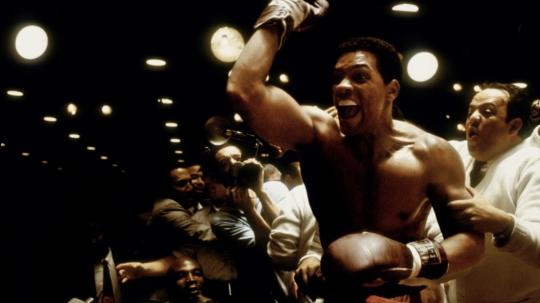

One of the most pivotal moments in Michael Manns career came in the year 2000, as he and cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki were location scouting for the directors long-gestating Muhammad Ali biopic Ali. After shooting digital video (DV) of potential settings at night, as reported in American Cinematographer magazine, both men began to fall in love with what they saw in their test footage. I was stunned by this one quality it had, which was not like moviemaking, Mann recalled years later, discussing his discovery of DV. There was a truth-telling style to the visuals, and the emotions were more powerful because it didnt feel theatrical. I analyzed afterwards what was going on to make me feel this way, and I realized it was because we had subtracted the theatrical lighting Everybody unconsciously sees it and knows that its something crafted, not something that feels real. That subtraction of the theatrical convention of how we light is very powerful.

From his earliest efforts, Mann had tried to find compelling ways to depict subjective experienceto get behind a characters eyes and find the emotional context of their actions. And digital photography gave him a tool that at once represented both the freedom and prison of subjectivity. On the one hand, as the director observed, it eliminated some of the artifice that so often mediates what were seeing onscreen; the video, especially when shot in low-light and natural conditions, had a jarring immediacy to it. At the same time, however, the pixellation lent everything an abstract quality, as if the images became more unstable the closer they got to reality.

Even as high-definition technology improved and the entire industry started shifting over to all-digital productions, Mann found ways to lean into the electric edge of video, highlighting its more otherworldly qualitiesqualities that would come to dominate the filmmakers later works. Instead of offering a more fluid, realistic experience, each new picture would prove to be even more fragmented, a canvas of competing perspectives, gestures, textures, and tones. This alienated audiences to some degree. Seemingly commercial, star-studded endeavors like Miami Vice (2006) and Public Enemies (2009), while they did have their share of vocal defenders, were relative disappointments at the box office, in part because viewers found the use of video to be awkward, disorienting, ugly.

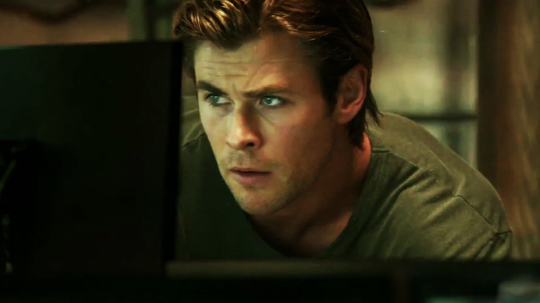

A similar sense of disappointment greeted Manns long-awaited cyber-thriller Blackhat when it was released in January of 2015. If anything, the backlash was even greater. While Miami Vice and Public Enemies had done some modest business, Blackhat proved to be an outright disaster. For Manns previous efforts, his studio, Universal, had stood behind him. “The key on looking at the profitability of Michael’s movies is that they’ve got a very long tail, well after the theatrical run,” the companys then-co-chairman Marc Shmuger said in 2006. [The films] do fantastically well in video, on all television outlets, overseas.“ But in the case of Blackhat, its expansion into several international territoriesincluding star Chris Hemsworths native Australiawas scrapped within a couple of weeks of the domestic release. (Frankly, were probably lucky we even got a Blu-ray.) It didnt fare much better critically. While some high-profile reviewers such as Manohla Dargis and Peter Travers praised the film, most were unimpressed and even annoyed.

A year after Blackhats release, at a Brooklyn Academy of Music retrospective of his work, Mann unveiled a directors cut that switched the order of certain major narrative developments, and brought a bit more focus to other characters besides Hemsworths. While this new version was an improvement, it did also delete certain important scenes from the film. Mann suggested at the time that he was still toying with the movie. Dont be surprised if yet another cut eventually emerges; even hes not entirely pleased with the picture, it seems.

Blackhat follows the efforts of a group of American and Chinese officials as they attempt to track down a mysterious hacker who has attacked a Chinese nuclear reactor and the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. To help them in this endeavor, the government allows convicted hacker Nicholas Hathaway (Hemsworth) to leave prison in exchange for his cooperation. Working together with an FBI agent (Viola Davis) and his old college roommate (Leehom Wang), now a captain in the Chinese army, Hathaway attempts to uncover not only the hackers identity, but also his motives and location.

Its a conventional crime movie set-up with a dose of ripped-from-the-headlines relevance. The run-up to the films release focused on the topicality of its premise, which was bolstered by the notorious Sony Pictures hack that resulted in millions of private emails from the movie studio being made public. Eventually determined to be a North Korean cyber-espionage operation designed to punish the studio for releasing the action-comedy The Interview, the Sony hack led to chaos and embarrassment for many in Hollywood and brought home to the rest of us the vulnerability of our online information. All of this seemed to feed interest in Manns latest project.