Truly Inconvenient Truths: The Island President and Issue Doc AestheticsBy Andrew Lapin

By Yasmina Tawil

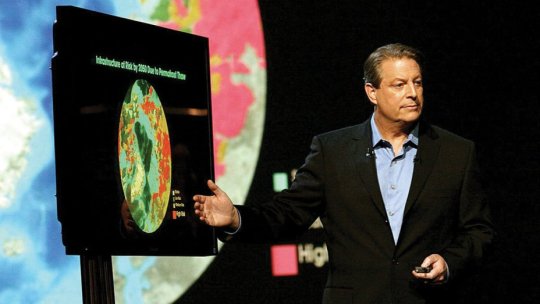

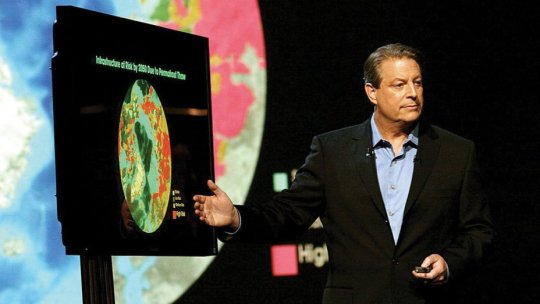

We like to say that documentaries can change the world. But the manner in which they change it matters. Ten years ago, when Davis Guggenheims An Inconvenient Truth sounded the alarm bells on man-made climate change, its aesthetic mission was clear: Al Gore, on a stage, flipping through slides.

An Inconvenient Truth wasnt trying to be a movie, at least not in the way we were used to seeing one. This was information, delivered in as no-frills a manner as possible, and distributed via movie theater. But it was valuable information, and that made the film culturally significant, a world-changer. An Inconvenient Truth grossed nearly $50 million worldwide, won two Oscars, and was instrumental in convincing millions of people around the globe of the urgent threat to our planet. It spawned dozens of imitators, issue docs that used a lot of charts and graphs to get a point across.

We have everything that we need to reduce carbon emissions, everything except political will, Gore says at the films conclusion. In what would become standard procedure for all documentaries distributed by Participant Media, the end credits came packaged with a list of things you, the viewer, can do to help: recycle, drive hybrids, and, of course, get other people to watch An Inconvenient Truth.

But is this style really the best way to communicate pertinent issues to the masses? Im talking about cinematic value here, but Im also talking about the way humans absorb information. Our very human-ness compels us to crave more than facts on a screen. We need narrative, characters, scope, stakes, and indelible images, laced with a touch of humor and a whole lot of pathos. We need, in short, cinema.