Too Big a Fail: Cannes Insta-Flops and the Festival Economyby Mike DAngelo

By Yasmina Tawil

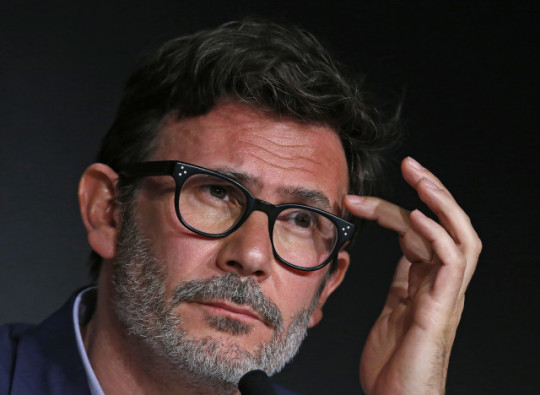

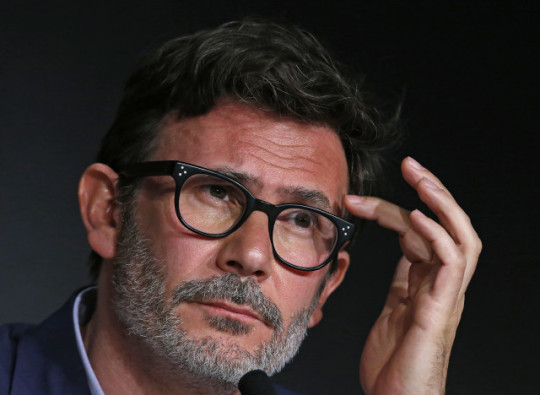

Cannes Film Festival, 2014. Among the films competing for the Palme dOr is The Search, Michel Hazanavicius highly anticipated followup to The Artist, which had won the Best Picture Oscar three years earlier (after itself debuting at Cannes). Its pedigree is flawless: based on an Oscar-winning (Best Story) 1948 drama of the same title, which had starred Montgomery Clift; a cast featuring former Oscar nominees Brnice Bejo and Annette Bening; weighty subject matter involving the Second Chechen War. When the press sees The Search, however, they rip it to shreds. A grueling, lumbering two-and-a-half hour humanitarian tract that all but collapses under the weight of its own moral indignation, Variety calls it, in one of the kinder reviews. Hazanavicius recuts the film slightly for its tour of the fall fest circuit, but it’s largely ignored, thanks to the toxic word out of Cannes. Today, over two years later, there is still no indication that The Searchwhich, lets just note again for the record, is the successor to a major box-office hit that won Best Picture, Director, and Actor at the 2012 Oscarswill get any sort of U.S. release.

Cannes Film Festival, 2015. Among the films competing for the Palme dOr is The Sea of Trees, a drama about an American man who flies to Japan with the intention of killing himself in Aokigahara, the infamous forest (see: The Forest; nah, dont see that) where locals commit suicide in alarming numbers. The film stars Matthew McConaughey, who had won the Academy Award for Best Actor just two years earlier (for Dallas Buyers Club); its director is Gus Van Sant, a previous Palme dOr winner (Elephant, 2003). Expectations are highuntil critics just about hoot The Sea of Trees off of the screen. One review accurately deems it “sub-Nicholas Sparks tripe,” a phrase that one wouldn’t generally anticipate when skimming the buzz from the world’s most prestigious film festival. Roadside Attractions, in conjunction with Lionsgate, had picked up the U.S. distribution rights in advance of the world premiere, but wound up sitting on the movie for over a year before finally selling it to adventurous new distributor A24. The U.S. trailer, released just this week, mentions the Cannes selection, but features no critical blurbs at allan almost unprecedented circumstance for an art film that premiered at a festival. (A24s trailer for The Lobster, which they picked up from financially troubled Alchemy, includes six blurbs from major critics.) Evidently, theyre hoping nobody will notice.