The Cat Who Wont Cop Out: Shaft as the 70s Black Superheroby Jason Bailey

By Yasmina Tawil

(The following essay is excerpt from Jasons new book, Its Okay With Me: Hollywood, the 1970s, and the Return of the Private Eye.)

The first thing John Shaft (Richard Roundtree) does in Gordon Parks Shaft, after emerging from a Times Square subway station below the grindhouse movie theaters that would eventually and enthusiastically screen his adventures, is walk into New York City traffic (Shaft cant be stopped, even by Eighth Avenue) and flip off the driver who gets too close to him. Meet your new action hero, Middle America; here is his message to you.

Shaft came early in the so-called blaxpoitation movementa period, running roughly from 1970 to 1975, that saw an explosion of films made for, about, and often by African-Americans. This was an underserved audience; with the exception of independent race picture makers like Oscar Micheaux and Spencer Williams, their stories simply werent told onscreen, and they certainly werent told by mainstream studio films, which consigned black performers to subservient roles (or worse). The winds started to shift in the 1960s, when Sidney Poitier became a bankable name and Oscar-winning star, but he was the exception to the rule. It wasnt until football star-turned-actor Jim Brown leveraged his supporting turn in the 1967 smash The Dirty Dozen into bona fide action hero status that this untapped swath of moviegoers, hungry for entertainment and representation, began to make itself known.

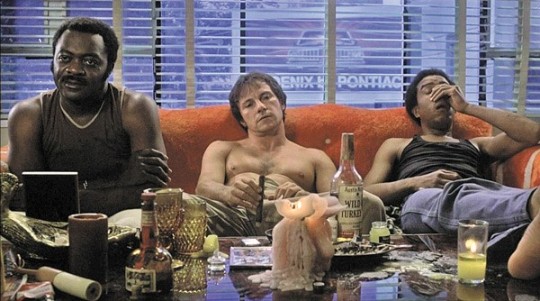

1970 saw the release of two very big (and very different) hits: Ossie Davis high-spirited crime comedy Cotton Comes to Harlem, and Melvin Van Peebles provocative, X-rated (by an all-white jury! boasted the ads) Sweet Sweetbacks Baadasssss Song. Peebles film was, essentially, the black Easy Rider, a rough-edged road movie with a decidedly European sensibility that grossed something like $15 million on a $150K budget, a return on investment so huge, the (flailing) studios couldnt help but take notice.

Shaft was next down the chute. Adapted by Ernest Tidymanwho also wrote that years Best Picture winner The French Connectionfrom his 1970 novel, the film was helmed by Gordon Parks, the influential photographer whod made his directorial debut in 1969 with the autobiographical The Learning Tree. MGM gave him a modest $1 million budget; model-turned-actor Roundtree was paid a mere $13,500 to play the title role. (Isaac Hayes was among the actors who auditioned, and though Parks passed on his acting, he hired Hayes to compose and perform the pictures iconic funk score.)

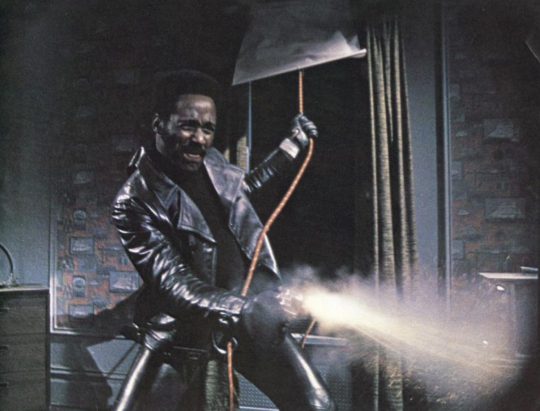

Shaft essentially was a standard white detective tale enlivened by a black sensibility, wrote Donald Bogle, in his essential Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies, & Bucks. As Roundtrees John Shaftmellow but assertive and unintimidated by whitesbopped through those hot mean streets dressed in his cool leather, he looked to black audiences like a brother they had all seen many times but never on screen. Hes right on both scores. Shaft, who is smirkingly called a black Spade detective, is embroiled in a commonplace private eye narrative, engaged by a lying client (uptown gangster Bumpy Jonas, smoothly played by Moses Gunn) to find a missing girlin this case, the clients daughter. Shaft is a snappy dresser and sharp shooter; he uses the neighborhood bar as his second office.

But weve never seen a private eye who looks like this. Shaft leaves the shirts and ties to the cops and gangsters; he wears turtlenecks with his suits, along with that amazing leather coat. In the documentary Baadasssss Cinema, blaxploitation acolyte Quentin Tarantino is critical of the lack of action in Shafts opening credit sequence (Im semi-frustrated that [the theme] wasnt utilized better, he explains. If I had the theme to Shaft to open up my movie, Id open my damn movie), but hes underestimating the visual jolt of merely showing a man like Shaft strutting the streets of New York, and gazing upon him as he stakes his claim.

Theres something undeniably sensual about that gaze. Shaft was among the first major motion pictures to feature a black man of sexual potencywith the phallic overtones embedded right in his surname, and thus in the films title. He gets a full-on sex scene with his steady lady early in the film; later on, he shares a steamy shower with a white pick-up, a mere four years after the carefully sexless interracial romance of Guess Whos Coming to Dinner.

But aside from that sceneand the iconographically loaded image, during the climax, of black militants turning fire hoses on white peopleShafts racial politics are surprisingly middle-of-the-road. Shaft may kid Lt. Vic Androzzi (Charles Cioffi) with lines like It warms my black heart to see you so concerned for us minority folks, but he humors the white cop, and mostly cooperates with him. The script is careful to disassociate its fictional black-power revolutionary group from real ones like the Black Panthers and the Young Lords, but it also shows them to be ineffectual, and Shaft is ultimately interested in their manpower, not their politics.