The Deepest Cut: The Hidden Emotion of Joel and Ethan Coen’s ‘The Man Who Wasn’t There’ by Mike D’Angelo

By Yasmina Tawil

Over the course of their three-decade career, Joel and Ethan Coen have buried a man alive, fed a body into a woodchipper, and shot a grinning Brad Pitt in the face at point-blank range. The most vicious act in their oeuvre, though, involves no physical violence whatsoever. It’s the blunt verdict issued by a famous French piano teacher, Jacques Carcanogues (Adam Alexi-Malle), after hearing a teenage girl’s audition. “Did she make mistakes?” asks the girl’s patron, who considers her a prodigy. “Mistake? No,” Carcanogues replies. “It say E flat, she play E flat. Bing, bing. She play the right note—always.” Nonetheless, he refuses to accept her as a pupil, insisting that her playing, while technically impressive, is emotionally sterile. “The music, monsieur, she come from l'intérieur. From inside. The music, she start here,” he explains, gesturing to his heart. Perhaps she might make a good typist, he suggests. “I cannot teach her to have the soul.”

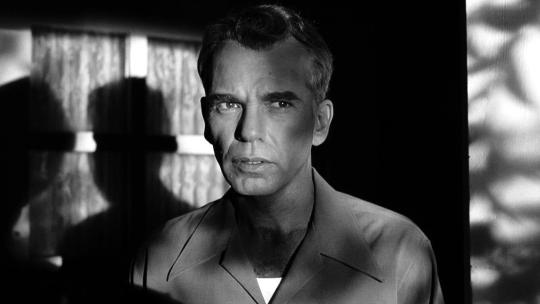

This exchange occurs late in The Man Who Wasn’t There, the Coens’ black-and-white film noir riff about a taciturn barber, Ed Crane (Billy Bob Thornton), whose spontaneous decision to invest in a dry-cleaning business (without having the necessary funds) leads to tragedy. At the time of the film’s release, in 2001, Carcanogues’ words pointedly echoed the most common criticism of the Coen brothers: that their films are superficially clever but fundamentally empty, little more than self-conscious genre riffs. That complaint doesn’t get lodged as frequently these days, in part because Joel and Ethan finally made an overtly personal movie, 2009’s A Serious Man, that reflects their own suburban Jewish upbringing. But The Man Who Wasn’t There remains their most wrenching cri de coeur, even if its heartfelt aspects are deliberately buried deep.

The film’s very first line, spoken by Ed in voiceover narration, insists that appearances don’t tell the whole story: “Yeah, I worked in a barber shop, but I never considered myself a barber.” Ed wants us to look past the surface—which is crucial, because the surface, when it comes to Ed, could hardly be more phlegmatic. Early on, he introduces us to his wife, Doris (Frances McDormand), and casually reveals that she’s having an affair with “Big Dave” Brewster (James Gandolfini), her boss at the department store where she works. Given the movie’s noir trappings, one might assume a crime of passion to be forthcoming…but Ed seems untroubled by the knowledge that Doris is stepping out on him, shrugging it off with the words “It’s a free country.” Nor does Ed and Doris’ marriage appear to be an especially happy one. They barely talk to each other—indeed, Ed barely talks at all, except in voiceover—and the relationship seems grounded in mutual tolerance. When Ed anonymously blackmails Big Dave about the affair, he explains the scheme strictly as an effort to get enough money to go into the dry-cleaning business. Passion doesn’t enter into it at all.

Or so the Jacques Carcanogues of the world would have you believe. But while Ed never comes out and states his feelings for Doris—that’s not his style—The Man Who Wasn’t There functions almost entirely as a stealth declaration of his love for her. It’s a film in which the motor driving every action purrs so softly that it’s barely audible. Stoicism, the Coens argue, isn’t necessarily the same thing as indifference, and things that look shallow (or frivolous, in the case of their work) may intentionally conceal hidden depths.