Lie To Me: The Multiple Personalities of Tom Waits Acting Career by Chris Evangelista

By Yasmina Tawil

I aint no extra baby, I’m a leading man.

Tom Waits, Goin Out West

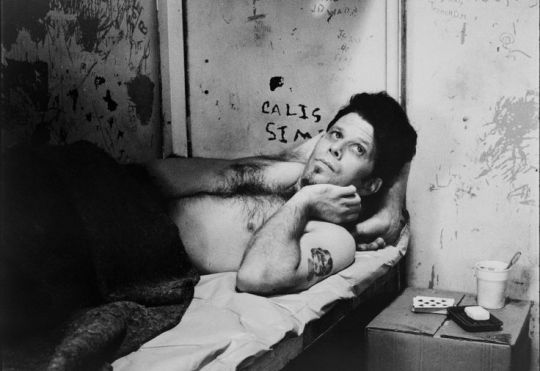

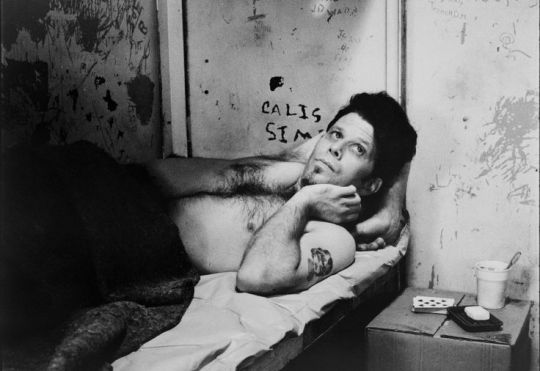

Tom Waits lights up the screen. The minute the singer appears in a film, he brings with him a sort of atmospheric baggagewe may not know what character hes playing, but we know him. We know that no matter what the film is, Waits will lend his own distinct, off-kilter brand of weirdness to it. Waits has been playing characters all through his musical career, the boozy troubadours and raspy-voiced noir loners who populate his songs are all engaging Waits creations.

Using his distinct, gravel-caked voice, Tom Waits conjures up boozy ballads designed to be played low at 3 a.m. and melodies that might echo off the broken-down rides of an abandoned, haunted carnival. His is an eclectic style, combining blues, jazz, cabaret, Spooky Sounds of Halloween sound effects tapes, and more. This distinct, unmistakable style goes beyond Waits musical accomplishments, finding its way into his acting in the two dozen or so film appearances the singer has made.

Waits doesnt consider himself foremost an actor. I do some acting, Waits tells Pitchfork. And theres a difference between I do some acting and I’m an actor. People dont really trust people to do two things well. If theyre going to spend money, they want to get the guy whos the best at what he does. Otherwise, its like getting one of those business cards that says about eight things on it. I do aromatherapy, yard work, hauling, acupressure. With acting, I usually get people who want to put me in for a short time. Or they have a really odd part that only has two pages of dialogue, if that.

Waits first film appearance was in Sylvester Stallones 1978 directorial debut Paradise Alley. Its a small part, with Waits essentially playing a version of himself, or at least the self he presents in many of his songs. The character, Mumbles, shows up at a piano, twitching and crooning. When was the last time you was with a woman? Stallones character asks him. Probably before the depression, Mumbles says. What are you saving it for? Stallone shoots back in that garbled manner of speaking Stallone has perfected. I dunno, Waits replies. Probably a big finish.

In the grand scheme of things, this is a nothing part; it was intended to be a bigger role, but Stallone cut it down to little more than a cameo. Yet what made it to the screen is distinct because Waits makes it so. Stallone is very still in the scene, leaning on Waits piano like dead weight. Waits is a study in contrast, never sitting still, his eyes half open. It might even be considered too much acting. When asked if acting came naturally to him, Waits replied, Its a lot of work to try and be natural, like trying to catch a bullet in your teeth.