Cogs in the Machine: American Despair in Paul Schraders Blue Collar by Vikram Murthi

By Yasmina Tawil

Paul Schrader’s directorial debut Blue Collar was supposedly inspired by stories of “real-life disillusionment.” Though that feeling certainly pervades the film from its opening minutes, the more appropriate term would be “utter despair.” The story of three “hard worked, fucked over men” who take on The Man and lose badly, Blue Collar stands among the class of films that attack the American Dream, the laughable ideal that “life should be better and richer and fuller for everyone” when it’s only ever destined for some. However, Schrader doesn’t merely bask in half-baked cynicism or preach cheap platitudes. Instead, he pulls no punches and confronts capitalism’s ills at their foundation, examining the hollowness of that Dream through a corrupt union’s indifference to the plight and desperation of its workers. It should come as no surprise that it tanked at the box office, or that the similar, more uplifting film Norma released the following year was a commercial and awards success. Norma didn’t intend to leave the audience with a bitter aftertaste.

Blue Collar’s script, written by Schrader and his brother Leonard, wholly immerses the audience into the compromised lives of three desperate Detroit autoworkers—Zeke (Richard Pryor), Jerry (Harvey Keitel), and Smokey (Yaphet Kotto)—who decide to rob their union headquarters to alleviate their financial woes. Though they only find $600 in petty cash, the trio also discovers a notebook containing records of the union’s illegal loan operation, implying ties to organized crime. When the gang tries to blackmail the brass, the tables are inevitably turned in a most heartbreaking fashion—murder, assimilation, and betrayal. Their Robin Hood caper becomes a cautionary tale of defying a corrupt establishment. They didn’t know that the game was rigged from the start.

But before Schrader brings the proverbial hammer down on his subjects, he first paints a portrait of a noxious work environment, which trickles down to its hopeless employees. As the credits roll, the film tracks rows and rows of equipment tended by workers shrouded in the bright glow of metal sparks, neatly introducing the cogs in a machine that incidentally manufactures literal machines. The working conditions are generally unsafe. The slave-driving supervisor, widely known and hated by everyone as Dogshit Miller (Borah Silver), rules the floor, getting on the nerves of every menial employee with his persistent nagging and casually virulent racism (“You pick cotton this slow?” he sneers at a black worker, who promptly gives Miller the finger as soon as his back is turned). Even the vending machines are busted, driving one frustrated worker (George Memmoli) to take revenge and destroy it on company time, costing him two weeks pay but making him a hero amongst the guys. A young, naïve worker (Ed Begley Jr.) reads Catch-22 in his off time without registering the irony.

Meanwhile, the main trio is perpetually in dire straits with seemingly no way out. Zeke cheats on his taxes to raise the income for his family, but when the IRS man (Leonard Gaines) shows up at his door one night, he learns that he owes almost $3000 in back taxes for claiming more children than he has and not disclosing a part-time job. “If I had the Navy and Marines behind me, I’d be a motherfucker, too!” he screams through a cracked voice as the taxman quickly leaves his home, knowing that Uncle Sam owns him just as much as the plant. Jerry, on the other hand, works a second job pumping gas to provide for his family, but he’s still in debt from a prior strike and can’t afford to pay for his daughter’s braces, prompting her to dangerously try to fashion them with a wire. Finally, Smokey owns money to violent loan sharks, and yet despite this unfortunate choice, Schrader characterizes him as the light amidst the darkness, a man who supplies his friends with intermittent joy in their otherwise difficult lives.

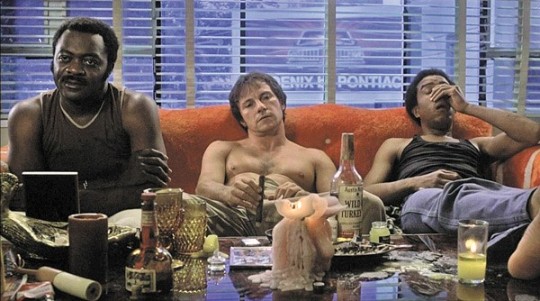

Schrader wholly sympathizes with the three men, even when Zeke and Jerry cheat on their wives and spend the little spare money they have on drugs. Despite their occasionally good spirits, the day-to-day drudgery of their lives perpetually threatens to crush whatever is left of their souls. Early in the film, Zeke, Jerry, and Smokey confess their anxieties after a coke-fueled night. Jerry takes out credit to pay for household appliances that he’ll likely never pay off. Zeke admits he’s terrible with money and that he knows he won’t be able to fulfill any of the promises he’s made his wife over the years. It’s a literal-minded scene, one that offers the audience a chance to merely sympathize with their plight instead of strenuously empathizing with their choices. Yet, Keitel and Pryor sell Schrader’s words with aplomb, filling them with equal parts rage and sadness. Though the scene technically preaches, it never scans as didactic, only honest.

While Blue Collar’s first half examines the reality of the workers’ lives, Schrader emphasizes the union brass’ abiding interest to maintain the status quo at all costs in the second half. Schrader initially characterizes the union as simply indifferent to the concerns of their workers, exemplified by Zeke’s broken locker that they don’t care to fix, but after the gang commits the robbery, he portrays the union’s actions as much more nefarious. Knowing that their corruption could be exposed, the union, led by boss Eddie Johnson (Harry Bellaver), sets out to silence or buy off the three men. They kill Smoky in a horrific paint-based accident on the factory floor and claim that it was an accident, as he’s the only one that they can’t control internally. They send mob guys after Jerry because he’ll buckle under any sort of violent pressure; after realizing he can’t outrun the mob, he becomes an informant for the FBI. Finally, Johnson promises Zeke a soft promotion to shop steward, knowing that the illusion of power will satiate his rage and allow them to keep him in their pocket for the foreseeable future.

Schrader’s script might be schematic insofar as after a certain point the film can really only end in “a very specific Marxist conclusion,” as he describes in a 1978 interview with Cinéaste, but this never registers on a moment-to-moment basis because the characters’ actions track logically and he mostly keeps the action on the ground floor. There’s recognition of evil deeds committed by the people upstairs, but they never arise above the dramatic level of sinister bigwigs who want to make money at the expense of people they swore to protect. We see the world through the lowlifes at the bottom who took a shot to challenge authority and ended up in an even deeper hole than they could possibly imagine. They’re pawns that always believe they’re in control right up until the moment they lose it.

Schrader swears in that same Cinéaste interview that he didn’t set out to make a left-wing film when he was writing Blue Collar. In fact, he bemoans leftist films that emphasize ideology over character, claiming that they don’t work dramatically and have no respect for their subjects.

“Aesthetically, you know, Che Guevara’s life is no more interesting than Rommel’s life. You could make a great, rich story about either one of them. As an artist, you have to hang your film on a character and let the character give you your strength, and if a critical feeling comes out of the character, all the better…That to me is the danger of so many left films—they know the thesis before they know the characters and the characters never live up to the thesis, and it has to work the other way around to have any dramatic sense. The left films I really like are the ones that love their characters.”

Schrader’s decision to privilege drama over ideology—essentially having the former lead the latter—ultimately strengthens the film’s politics. His demonstrable love for his characters makes their fates that much more devastating, and in turn emphasizes the political weight of the film’s thesis. In Blue Collar’s clumsiest moment, Smokey explains to Zeke and Jerry that the union only wants to keep them in check, and that they’ll pit workers against each other, primarily along racial or generational lines, to distract them from the real top-bottom malfeasance. While this brief explication needlessly points a large arrow towards the film’s potent subtext, it nevertheless lends a heavy melancholic overtone to the film’s final act, as we see how Zeke and Jerry eventually turn on each other and fall back on racial animosity to fuel their division.

Schrader’s idealized depiction of racial harmony between the trio breaks apart when Jerry and Zeke can no longer understand the compromises they’ve both made. In their final talk as friends, Zeke tells him that he took the promotion and returned the stolen notebook because he knows he’ll never receive the same opportunities as a white man. Jerry balks at his suggestion, since they both know the union’s involvement in Smokey’s death and that their corruption will remain the same, but Zeke calmly informs him that if he has to kiss ass, he wants to choose the ass he kisses. It’s a startlingly honest conversation about race between two men on opposite ends of the color divide, and how some will never be able to understand the compromises others make just to keep on moving forward. Even as Schrader breaks Zeke and Jerry apart for reasons they don’t (or can’t) understand in the moment, he never robs them of their own personal dignity or self-awareness.

Jerry walks away from Zeke’s house with an offer to take over as supervisor and with the knowledge that his last friend sold out their chance to expose a corrupt, violent union. Though he might have the moral high ground, he can’t empathize with Zeke’s perspective or his unique life experience in a crucial moment, and thus their relationship shatters.

The final scene culminates in blows and a messy freeze frame. Both Zeke and Jerry call each other out for being a sellout and an informer respectively. These once close friends, who shot the shit and partied and whose families went bowling together, are now exchanging racial epithets because of their interpersonal betrayal. In the process, they’ve completely forgotten that it was the union who sold them out to begin with, and that they wouldn’t be there in the first place if the institutions they trusted didn’t look out solely for themselves at the expense of their charges. Schrader repeats Smokey’s subtext explanation in voiceover, and though it’s a heavy-handed aesthetic move, it does provoke chills in spite of itself. It’s fairly impressive that a mainstream Hollywood film ends on this note, that those in power will exploit racial discord in order to keep desperate workers divided, because they instinctively know that if those workers joined forces, they could overthrow the whole damn system.