A series examining the output of a single studio in a single calendar year.

PROLOGUE

For RKO Pictures, 1952 really began on March 23, 1951. That was the day U.S. Marshal Charles W. Ross went to the home of screenwriter Paul Jarrico to deliver a subpoena ordering him to appear before the House Committee on Un-American Activities. The most important events at RKO in 1952—a year in which the studio released films from Nicholas Ray, Josef von Sternberg, Howard Hawks, Fritz Lang, and Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger—had nothing to do with cinema. Instead, studio chief Howard Hughes spent that year of the blacklist transforming RKO into a club to swing at Communists, before selling the entire company to capitalists so pure they crossed the line into organized crime. By year’s end, the studio had played an integral part in ceding Hollywood power to Washington, with consequences that would define the next decade in film. RKO’s films were almost an afterthought. And it all began with that knock on Jarrico’s door.

Paul Jarrico’s subpoena was one of a group of eight issued by the House Committee early in March 1951, which opened Congress’s second round of hearings with Hollywood. The initial hearings in 1947 had led to contempt of Congress convictions and jail time for the Hollywood Ten, the original group of screenwriters and directors who’d refused to answer questions about their membership in the Communist Party. But although right-wing publications like Red Channels had pursued the idea that Hollywood had been infiltrated by subversive agents, Congress hadn’t re-addressed the issue. Jarrico, along with several of his compatriots, managed to initially avoid the subpoena servers; the Communist Party was testing various approaches to dealing with HUAC and disappearing was one of them. But they did find Larry Parks, an actor in Jarrico’s batch of subpoenas. On March 21, in a closed-to-the-public “executive session,” Parks gave the names of other party members. Details of the closed session were immediately leaked; when the news broke, Jarrico resurfaced and issued a public statement that left no doubt where he stood on the issue of naming names:

“If I have to choose between crawling in the mud with Larry Parks or going to jail like my courageous friends of the Hollywood 10, I shall certainly choose the latter.”

“Crawling in the mud” was actually Parks’s term for his own testimony, not Jarrico’s, but it wasn’t a good year for nuance. Jarrico’s stand had long-reaching consequences for his career, and for RKO, where he’d been revising a film called The Las Vegas Story. Howard Hughes, running the studio at the time, was a hardline anti-Communist who had no patience for Jarrico’s public scorn toward informers. The day the subpoena was delivered, he had Jarrico turned away at the studio gate without so much as a chance to clean out his office.

For whatever it’s worth, Paul Jarrico was a member of the Communist Party—in fact, in the mid-1950s, he was the head of the Hollywood section. (“I presided over its liquidation,” he’d later tell Patrick McGilligan for his great oral history of the blacklist Tender Comrades.) But the idea that Communist screenwriters were working to overthrow the United States government was nonsense. Jarrico described the Party for most of the time he was a member as “the tail to the liberal-Democratic kite,” and didn’t see any contradiction between his political beliefs and his patriotism.

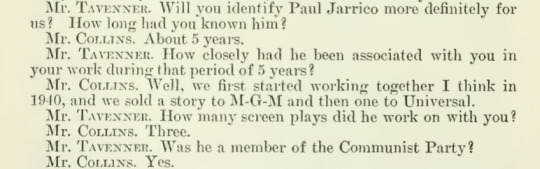

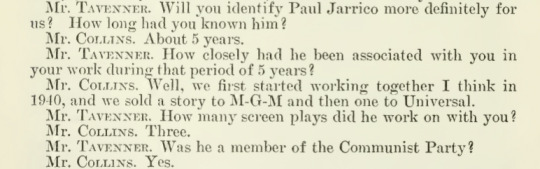

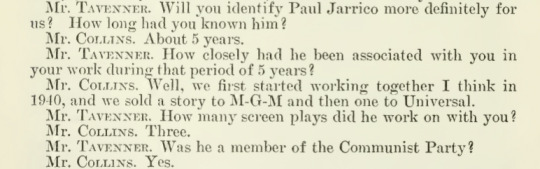

Jarrico faced the committee in Washington on Friday, April 13, 1951, and struck something of a conciliatory tone, at least toward RKO. Asked what he’d been working on, he replied, “…The Las Vegas Story, which is currently shooting in Hollywood. I urge you all to see it.” But the committee had learned from its mistakes in 1947, and the hearings were orchestrated to make it impossible for unfriendly witnesses to come out unruined. In Jarrico’s case, his one-time writing partner, Richard J. Collins, had been scheduled to name him as a member of the Communist Party—along with everyone else he could remember—in an open session the day before Jarrico testified.

Jarrico later chalked this up to professional jealousy: he and Collins had collaborated on Song of Russia, a pro-Soviet Union film made at MGM while the USA and USSR were World War II allies. In Jarrico’s recollection, Collins did very little of the work, and Jarrico broke up the partnership. Collins named him, Jarrico said, because “he wanted to stand on his own two knees.” But regardless of his motivations, by the time Jarrico was sworn in, there was hardly anything for him to do but react to Collins’s allegations. He showed up with a statement but the committee wouldn’t let him read it; he refused to answer any questions about his Communist Party membership on Fifth Amendment grounds (in 1947, the Hollywood Ten had refused to answer on First Amendment grounds, which left them open to contempt of Congress charges). Jarrio wasn’t entirely silent, however, and the Committee wasn’t able to control all of his testimony. When asked if he would help uncover anyone who was “subversive in their attitude toward the constitutional form of government in our Nation,” Jarrico replied that he considered the Committee on Un-American Activities to be one such subversive organization. And he had this rather remarkable exchange with Representative Clyde Doyle (D-CA), who asked if Jarrico had any suggestions for legislation to help the Committee be more effective in finding subversives. Jarrico told him he had one idea:

“You might revise your guide to subversive organizations and publications issued by this committee. It includes, for instance, the Hollywood Democratic Committee, and, without wishing to embarrass you, Congressman Doyle, perhaps you remember that that committee contributed to your campaign and wrote speeches for your campaign. It is listed here as a subversive organization.”

This moment didn’t make the newspapers—the New York Times, for example, focused on Jarrico’s refusal to talk, and ran a photo of him, arms crossed, looking petulant. But they did run part of the statement the committee wouldn’t let him read:

“I am proud of my beliefs. I am proud of my affiliations. I’ll be damned, though, if I’ll disclose them to my enemies to be used against my friends.”

It wasn’t a good season for standing on principle. Although Doyle told Jarrico, incredibly, “we are not interested in blacklisting anyone,” RKO had already fired him, and no further work was forthcoming. That left The Las Vegas Story, already in production. Hughes ordered immediate rewrites to throw out everything Jarrico had done, but writing credits, then as now, were assigned by the Screen Writers Guild (an ancestor of the Writer’s Guild of America). On September 19, 1951, after evaluating the work done by all writers, the Guild notified RKO that The Las Vegas Story’s screenplay should be credited to Earl Felton, Harry Essex, and Paul Jarrico. The collision course was set.

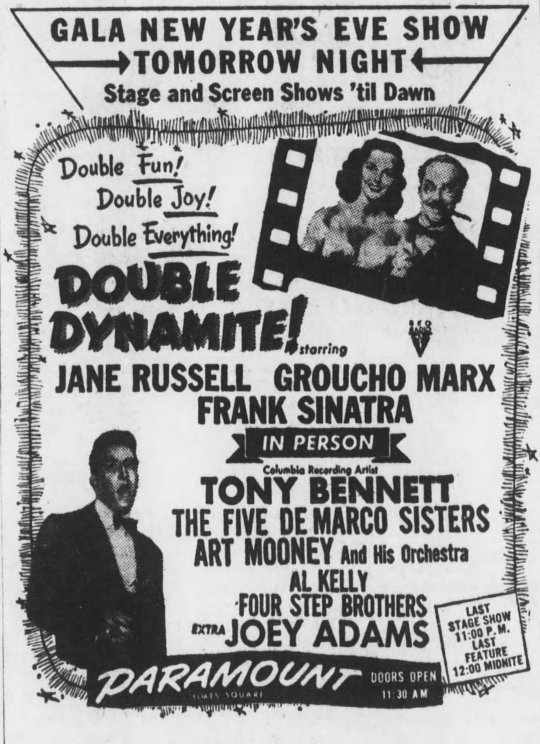

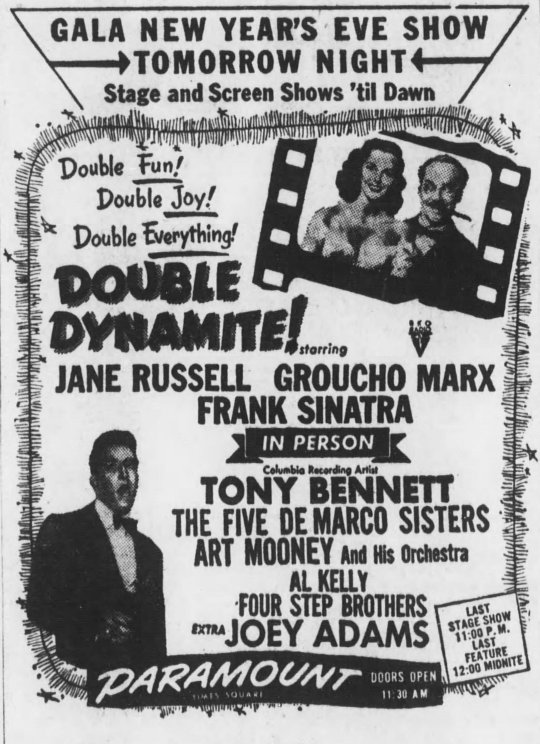

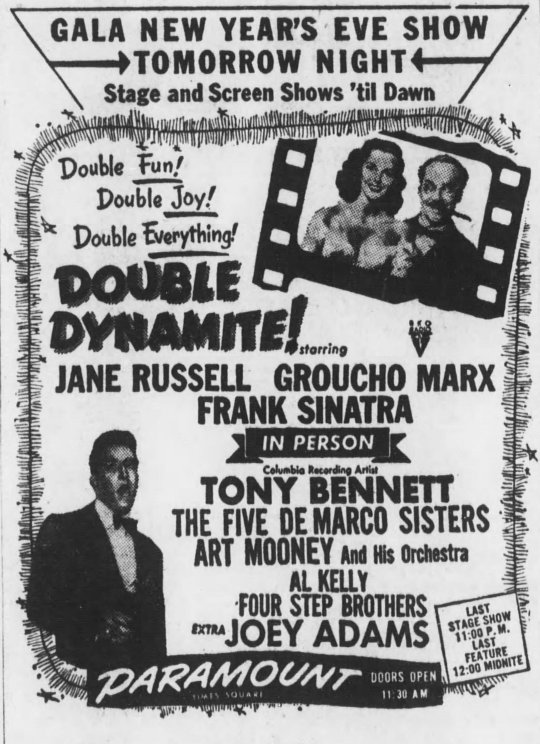

WINTER

Summer blockbuster season wasn’t a thing yet in 1952, but January was already a dumping ground. RKO had opened three films over Christmas, 1951, which were still making their way across the country throughout January (and, indeed, throughout the year) in those days before wide releases. In Boston, you could see On Dangerous Ground, a Nicholas Ray film starring Ida Lupino and Robert Ryan that swoons from noir to melodrama. In New York, the Little Carnegie Theater reopened after renovations with Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon, an RKO acquisition. The rest of the country had to make do with RKO’s wider release that season: Double Dynamite, a Jane Russell vehicle whose title, the advertising made clear, meant exactly what it sounded like. Of course, you could see Double Dynamite in New York or Boston, too—at New York’s Paramount Theater, the film, which featured Frank Sinatra, was accompanied by a live performance from Tony Bennett.