Cogs in the Machine: American Despair in Paul Schraders Blue Collar by Vikram Murthi

By Yasmina Tawil

Paul Schraders directorial debut Blue Collar was supposedly inspired by stories of real-life disillusionment. Though that feeling certainly pervades the film from its opening minutes, the more appropriate term would be utter despair. The story of three hard worked, fucked over men who take on The Man and lose badly, Blue Collar stands among the class of films that attack the American Dream, the laughable ideal that life should be better and richer and fuller for everyone when its only ever destined for some. However, Schrader doesnt merely bask in half-baked cynicism or preach cheap platitudes. Instead, he pulls no punches and confronts capitalisms ills at their foundation, examining the hollowness of that Dream through a corrupt unions indifference to the plight and desperation of its workers. It should come as no surprise that it tanked at the box office, or that the similar, more uplifting film Norma released the following year was a commercial and awards success. Norma didnt intend to leave the audience with a bitter aftertaste.

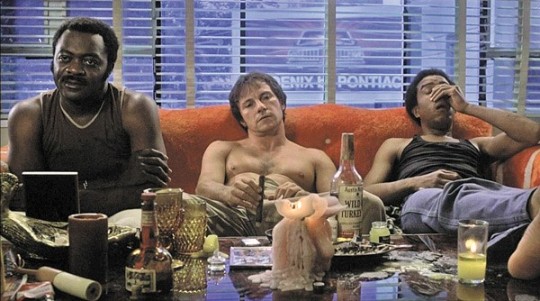

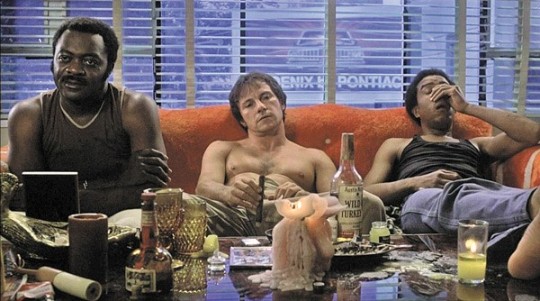

Blue Collars script, written by Schrader and his brother Leonard, wholly immerses the audience into the compromised lives of three desperate Detroit autoworkersZeke (Richard Pryor), Jerry (Harvey Keitel), and Smokey (Yaphet Kotto)who decide to rob their union headquarters to alleviate their financial woes. Though they only find $600 in petty cash, the trio also discovers a notebook containing records of the unions illegal loan operation, implying ties to organized crime. When the gang tries to blackmail the brass, the tables are inevitably turned in a most heartbreaking fashionmurder, assimilation, and betrayal. Their Robin Hood caper becomes a cautionary tale of defying a corrupt establishment. They didnt know that the game was rigged from the start.

But before Schrader brings the proverbial hammer down on his subjects, he first paints a portrait of a noxious work environment, which trickles down to its hopeless employees. As the credits roll, the film tracks rows and rows of equipment tended by workers shrouded in the bright glow of metal sparks, neatly introducing the cogs in a machine that incidentally manufactures literal machines. The working conditions are generally unsafe. The slave-driving supervisor, widely known and hated by everyone as Dogshit Miller (Borah Silver), rules the floor, getting on the nerves of every menial employee with his persistent nagging and casually virulent racism (You pick cotton this slow? he sneers at a black worker, who promptly gives Miller the finger as soon as his back is turned). Even the vending machines are busted, driving one frustrated worker (George Memmoli) to take revenge and destroy it on company time, costing him two weeks pay but making him a hero amongst the guys. A young, nave worker (Ed Begley Jr.) reads Catch-22 in his off time without registering the irony.

Meanwhile, the main trio is perpetually in dire straits with seemingly no way out. Zeke cheats on his taxes to raise the income for his family, but when the IRS man (Leonard Gaines) shows up at his door one night, he learns that he owes almost $3000 in back taxes for claiming more children than he has and not disclosing a part-time job. If I had the Navy and Marines behind me, Id be a motherfucker, too! he screams through a cracked voice as the taxman quickly leaves his home, knowing that Uncle Sam owns him just as much as the plant. Jerry, on the other hand, works a second job pumping gas to provide for his family, but hes still in debt from a prior strike and cant afford to pay for his daughters braces, prompting her to dangerously try to fashion them with a wire. Finally, Smokey owns money to violent loan sharks, and yet despite this unfortunate choice, Schrader characterizes him as the light amidst the darkness, a man who supplies his friends with intermittent joy in their otherwise difficult lives.