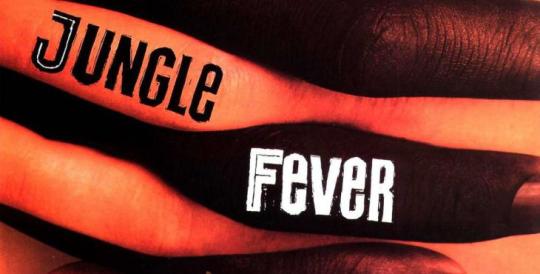

With Jungle Fever, Spike Lee Brought Cultural Taboos to A Theater Near YouBy Scott Tobias

By Yasmina Tawil

Agree or war has been our way of compromising/ Let live and love has become our greatest lie.

Stevie Wonder, Feeding Off the Love of the Land

Toward the middle of Spike Lees Jungle Fever, a group of black womena war counsel, as Lees character, Cyrus, jokingly refers to themgather together to drink wine and sift through the remains of a broken relationship. Their friend and host, Drew (Lonette McKee), has kicked her husband, Flipper (Wesley Snipes), out of their tony Harlem brownstone for having an affair with Angie (Annabella Sciorra), an Italian temp at his architectural firm. Drews friends dutifully decry the evils that men do (Theyre all dogs), but the conversation gradually shifts and expands, as conversations do, into more unexpected and compelling areas. Among the topics on the table: The finite number of good black men and the white bitches who throw themselves at them; the hang-ups men have with professional women; dating proclivities (Im not the rainbow-fucking kind); the twin stigmas of light and dark skin; and the difficulties of sustaining a committed relationship.

You know something, though? Drew sighs ruefully at the end of it. It doesnt matter what color she is. My man is gone.

Let us appreciate, for a moment, that 25 years ago, an American studio paid for this conversation and brought it to theaters nationwide. Having scored a hit with Lees galvanizing Do the Right Thing two years earlierand bankrolled the somewhat less sensational Mo Better Blues the year after thatUniversal Pictures recognized the directors value as a frugal provocateur at a time when studios were more inclined to make small gambles. Lees sensibility hasnt changed much in years since, but the landscape has shifted dramatically: His last two films, Da Sweet Blood of Jesus and Chi-Raq, have emerged from Internet pipelinesKickstarter and Amazon Studios, respectivelythat didnt exist until recently and would have been completely inconceivable in 1991. But along with what could euphemistically be called Lees return to his independent roots come the consequences of limited exposure. To varying degrees, Da Sweet Blood of Jesus and Chi-Raq got batted around in the press and in big-city arthouses; Jungle Fever was now-playing-at-a-theater-near-you.

Consider the implications: Its one thing to bring New Yorkers into Drews living room, where moviegoers are keenly aware of the cultural taboos and terrain, but its quite another to venture into the multiplexes of Missoula, Montana or Kennesaw, Georgia (where I saw the film) and be confronted by characters and problems of an uncommon complexion. In the suburbs and small towns, white Americans had spent the previous decade imagining the city as a war zone for Charles Bronson to bust up or the scary place the Griswalds drove through on their way to Walley World. With a film like Jungle Fever, Lee could upend assumptions simply by virtue of opening his mouth and describing the world as he understands it. A Romeo & Juliet affair between a black man from Harlem and a white woman from Bensonhurst? The varying burdens of skin pigmentation? The magisterial squalor of an inner-city crack den? For many, he was making foreign films without subtitles.