From ‘An Early Frost’ to ‘The Normal Heart’: The Shifting Sands of the AIDS Narrative on Film by Craig J. Clark

By Yasmina Tawil

“People are dying so fast that it’s like what I imagine being in a war would be like.”

–volunteer nurse Hedy Straus in the 1987 documentary short Living With AIDS

By the time Ronald Reagan deigned to mention AIDS publicly for the first time in a press conference on September 17, 1985, it was known in some circles that the virus that causes it had been ravaging the gay community for more than four years. In the interim, while the medical and scientific communities scrambled to get a grip on the epidemic and fought for the government funding needed to do so properly, gay writers and filmmakers responded to the health crisis in their own way—by creating plays and films that humanized its victims and had the potential to educate the American public about the need for compassion and swift action.

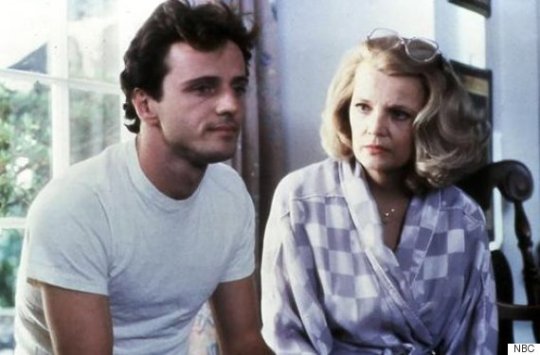

One of the most immediate of these responses was Larry Kramer’s play The Normal Heart, which the outspoken writer/activist—a founding member of Gay Men’s Health Crisis in 1982, when the disease was still known as GRID, or Gay-Related Immunity Disease—started writing in 1983 and saw staged to great acclaim at New York City’s Public Theater in the spring of 1985. Another project with a similar gestation period was the pioneering TV movie An Early Frost, broadcast by NBC that fall after co-writers and partners Ron Cowen and Daniel Lipman—who later went to develop Queer As Folk for Showtime—went through 15 drafts with the network over a year and a half. And first-time filmmaker Bill Sherwood’s low-budget indie Parting Glances was shot in 1984—as evidenced by the new releases lining the wall in one scene set at a trendy record store—but didn’t get released until early 1986. Snapshots of a time when there was a great deal of misinformation about AIDS and the people it affected, all three remain urgent dispatches from the front lines of the struggle. But to keep them straight, it’s helpful to take them in the order they reached the screen, touching on a few other milestones along the way.

“I’m sure you’ve heard of Acquired Immunity Deficiency Syndrome.”

For all its good intentions, An Early Frost wasn’t the first feature film about AIDS. In his seminal text, The Celluloid Closet: Homosexuality In The Movies, Vito Russo gives that distinction to Arthur J. Bressan, Jr.’s Buddies, and he’s supported by Raymond Murray’s Images in the Dark: An Encyclopedia Of Gay And Lesbian Film And Video. According to Murray’s book, however, Buddies was never released on video and it continues to be unavailable to stream or purchase, which has rendered it as invisible today as AIDS sufferers were to the general public three decades ago. By contrast, An Early Frost was put out on DVD in 2006, complete with a commentary by Cowen, Lipman, and lead actor Aidan Quinn, plus the documentary short Living With AIDS, which was filmed by producer/director/editor Tina DeFeliciantonio in 1985 and broadcast on PBS a couple years later. A huge ratings-getter, An Early Frost beat out Monday Night Football to be the top-rated show of the night, capturing one-third of the total viewing audience when it premiered. Today, it takes viewers back to a time when AIDS was a death sentence for nearly everyone who contracted it and effectively outed those who were still in the closet.