No Exit to Brooklynby Ryan Wu

By Yasmina Tawil

In the opening scene of Westminster, Trinh, a Vietnamese shopgirl, tells her boss that she’s moving to California to work at a nail salon. She explains that her prospects in Vietnam are bleak, and that however despondent she is to leave her beloved mom and sister behind, she has their blessing to seek a better life. Then, after enduring an arduous journey across the Pacific aboard a container ship, she settles in a cramped boarding house above the nail salon. She makes fitful efforts to befriend the vicious gossips who perform mani-pedis alongside her, but mostly she feels alienated and alone. Then, while in line at a boba shop, Trinh meets Joon, an earnest Korean-American dental student. In the midst of their cross-ethnic courtship, Trinh is summoned back to Vietnam…

Westminster, of course, doesn’t exist. However, the Irish version of the same story, Brooklyn, found purchase with critics and arthouse audiences alike, grossing $61 million in North America (on an $11 million budget) and nabbing three Oscar nominations. If success begets imitators in the movie business, why does a 200-screen release of Westminster—or Pico-Union, another hypothetic feature but about an El Salvadorian naïf’s struggles in urban America—seem so improbable?

And what does it say about America in Annus Trumpilis that the only migrant story widely screened over the past year features a blonde Irish lass? After all, only 11% of American emigres in 2014 hail from Europe. A far greater number of new immigrants, representing 30% of the total in 2014, come from Asia, with another 24% from Central and South America. If the upcoming election supposedly pits an emerging diverse America against the “Make America Great Again” crowd of white nostalgia, Hollywood—or maybe the moviegoing public—wears a red cap.

For all the noise of #oscarsowhite, the discordant note struck by feting Brooklyn slipped completely under identity activists’ radar. To be sure, we shouldn’t expect (or want) art to speak directly to the topic du jour, no matter how hotly debated. It would be churlish to begrudge the existence of a lovely, if imperfect, film like Brooklyn that graced us with Saoirse Ronan’s radiant Eilis. But it’s striking that Eilis’s core dilemma—the agonizing choice between a young, confident America of infinite possibility and the comfort and joy of the old country—speaks primarily to contemporary viewers who look nothing like her. As a child of immigrants, it’s hard not to conclude that the yearning and struggles of my parents only make it on screen when they’re embodied by a young blonde.

But what I found most disappointing about Brooklyn, at least on a first viewing, isn’t so much its whiteness as its conventionality. Aside from Eilis’s bracing opacity—she seems at once precisely drawn and fundamental unknowable—the film had the feel of a prestige product by the numbers.

On a subsequent viewing, the tropes look more like a strategy to pare the film to its irreducible core. Brooklyn creates a familiar world out of half-remembered images of old movies: the ship’s approach into Lower New York Bay shown in a thousand movies, the rural Irish landscapes of Housekeeping, the white ethnic cornucopia of post-war Brooklyn in Sophie’s Choice, the grittiness of Angela’s Ashes. Even the characters fit into familiar types, as Eilis falls in love with an earnest Italian-American Brando and then with an Irish-Irish Jimmy Stewart. Brooklyn’s inheritance of this rich iconography relieves the filmmakers from having to laboriously walk viewers through Eilis’s culture shock, or providing a beginner’s guide to the Italian-Irish tension in New York.

Another recent period piece, James Gray’s The Immigrant, is likewise steeped in the iconography of the émigré tale, opening with a view of the Statute of Liberty through gauzy mist. Set in 1921, The Immigrant takes Marion Cotillard’s dignified Eva through a tour of iconic locales like Ellis Island and the Lower East Side, where she could’ve crossed paths with the young Vito Corleone. Where Brooklyn portrays an America of song and myth, the America in The Immigrant is menacing and pitiless. Gray dives into the country’s seedy underbelly, chronicling the death of the American Dream in the crowded bathhouses and at the Bandit’s Roost, where a rag-tag band of strippers, magicians and pimps gather.

Building on the iconography of 20th Century émigré film, both Brooklyn and The Immigrant are free to burrow into little odd corners. They’re able to tell stories in a minor key, without needing to march the viewer through a ham-fisted account of the representative European-American experience. (The maturity of this subgenre frees up filmmakers to take bold experiments, as Lars von Trier did in Dancer in the Dark and Dogville, rendering the immigrant story into pure abstraction.)

Asian and Latino stories, deprived of this shared body of films, have to create their own mythology and shorthand. With that comes growing pains. If we haven’t yet seen a termite artist making an Asian-American The Immigrant, it might be because these filmmakers too often lapse into the habit of translating rather than portraying.

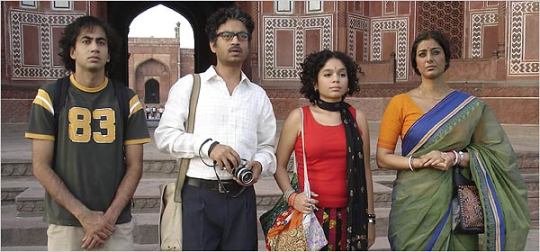

Consider The Namesake, perhaps the closest thing to an Asian-American Brooklyn. Like Brooklyn, The Namesake is an adaptation of a beloved, prize-winning novel. And with Indian-American star Kal Penn in front of the camera and the Oscar-nominated Mira Nair behind it, it appeared to be a can’t-miss.

The early scenes set in India are fine, particularly a “meet cute” where the gorgeous Ashama (Tabu) tries on a pair of American-welded brogues belonging to her suitor, Ashoke Ganguli (Irrfan Khan), a bookish grad student living in New York. The catch is that this is an arranged marriage, and as the young couple make their way to New York, Ashama fumbles through a strange world, grasping to what she knows (like adding nuts to Rice Krispies). In these lyrical passages, Nair’s expressionism is married to a storytelling economy that promises something genuinely exciting.

But the focus soon shifts to their American-born son Gogol (Penn), who’s able to glide effortlessly into WASP society. The film painstakingly sets up a dichotomy between Gogol’s aspiration to erase his ethnic difference and his Bengali roots. But Gogol’s dilemma takes on an increasingly melodramatic tone as he oscillates between his insensitive WASP girlfriend Maxine (a laughable caricature) and his now sanctified parents. Like other failed stories of assimilation like The Joy Luck Club, The Namesake becomes too eager to serve as a white viewer’s emissary to a foreign culture, abandoning observational detail and nuance in the process.

Too many of these pictures bear the hallmarks of the pioneer’s burden. Like the first black baseball player, or the first Latino Supreme Court Justice, filmmakers aspiring to tell the (nonwhite) immigrant’s story—at least on a sizable budget— perceive a special responsibility to carry the torch for the group while losing their own voice. Thus far, too many have erred on the side of the former, crafting picture menus of exotic items for white patrons.

It’s a tough dilemma. To break through commercially, Asian-American filmmakers often perceive that any cultural differences must be strenuously Wiki’d and footnoted so as to not alienate the older white audiences that make up the vast majority of arthouse patrons. Yet in that path lies artistic mediocrity. I saw these pressures exerted on filmmakers as one of programmers of the Los Angeles Asian Pacific American Film Festival. Over the past year, I encountered dozens of micro-budget indies where filmmakers take chances with genre and subject matter, making schlocky vampire movies or Coen Brothers-inspired dark comedies. But I also saw dozens of higher-budgeted (mid-six figure) pics, aspiring to commercial distribution, that suffer from ponderous over-contextualizing.

Ultimately, the lack of a vibrant, commercially viable Asian-American cinema can’t just be attributed to Hollywood’s perfidy and biases. The problem is more ingrained and systemic. But I think change is coming, spearheaded by the diversity explosion on television. With shows like Master of None, Fresh Off the Boat, and Crazy Ex-Girlfriend penetrating mainstream culture, Asian-American settings and character types are no longer so alien. In time, minority filmmakers will also reap the benefits. After all, why aspire to make a garden-variety Tamil immigrant movie when the story of Dev’s parents has already been told? Why not take a chance? So maybe in 2022, we will see a character-focused, atmospheric Westminster, playing on 200 screens.