The Counselor: No Movie for Most Men (or Women)by Mike DAngelo

By Yasmina Tawil

[This month, Musings pays homage to Produced and Abandoned: The Best Films You’ve Never Seen, a review anthology from the National Society of Film Critics that championed studio orphans from the ‘70s and ‘80s. In the days before the Internet, young cinephiles like myself relied on reference books and anthologies to lead us to film we might not have discovered otherwise. Released in 1990, Produced and Abandoned was a foundational piece of work, introducing me to such wonders as Cutter’s Way, Lost in America, High Tide, Choose Me, Housekeeping, and Fat City. (You can find the full list of entries here.) Over the next four weeks, Musings will offer its own selection of tarnished gems, in the hope they’ll get a second look. Or, more likely, a first. —Scott Tobias, editor.]

Most people prefer movies to be affirming, in some way. Life-affirming, love-affirming, norm-affirming—just so long as something we believe (or want to believe) gets reinforced, everybody’s happy. Declining to satisfy that desire is step one en route to making an art film, or what publicists who are nervous about the word “art” like to call a specialty release. These, too, cater to viewers’ preconceived notions about the world (good luck finding something that doesn’t), but they target notions that are less commonly held, which makes them less commercially viable. Deriving enjoyment from genuinely despairing or pessimistic movies is a taste that must be acquired, and only a small subset of the population has the time or the inclination. These are the folks who’ll go see a Moonlight, say, or a Manchester By The Sea. They’re game.

It’s possible to alienate these adventurous, open-minded viewers, too, though, by making a movie that’s not just challenging or upsetting, but flat-out nihilistic. A movie that assumes the worst about human nature, with few (if any) mollifying grace notes. A movie that, at least to some extent, glorifies venality and ugliness. “Alienate” is too mild a word for the common reaction, actually. They will be pissed off.

Such was the reception that greeted The Counselor back in 2013. Expectations for the film were sky high: It features a superb cast (Michael Fassbender, Pénélope Cruz, Javier Bardem, Cameron Diaz, and Brad Pitt); was directed by Ridley Scott (a decidedly erratic talent, but still capable of greatness); and, most exciting of all, boasts a screenplay from Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Cormac McCarthy. McCarthy’s books had been adapted several times—most notably by the Coen Brothers, whose version of No Country for Old Men won multiple Oscars—but he’d never before written an original story expressly for the big screen. Had The Counselor been made available intravenously, many would have mainlined it without hesitation.

Cue the adrenaline-shot scene from Pulp Fiction. Not all of the Counselor reviews were negative, by any means, but the critics who hated it really, really hated it. “Meet the Worst Movie Ever Made” ran the headline on Andrew O’Hehir’s savage takedown at Salon, and that wasn’t some editor’s hype; in the actual piece, O’Hehir expands his assessment to “the worst movie in the history of the universe,” thereby dismissing the possibility that alien life forms in faraway galaxies may possibly have committed an even greater sin against cinema. Other reviews in major publications deemed the film “lethally pretentious,” “a jaw-dropping misfire,” and “unforgivably phony, talky and dull.” (Characters do indeed talky on the phony sometimes.) Audiences were similarly repulsed: The Counselor got a dismal D in Cinemascore’s survey, which generally skews so positive that you can currently find an A- assigned to the likes of Assassin’s Creed (Metacritic score: 36/100) and Collateral Beauty (Metacritic score: 23/100). It’s not a popular title.

Here are a few reasons why many people seem to hate it:

- The narrative is ludicrously convoluted.

- All of the characters speak primarily in lengthy philosophical monologues.

- It’s just a catalogue of horrible things happening to people who mostly deserve them.

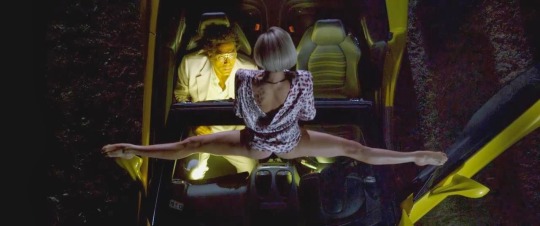

- Cameron Diaz fucks a car.

We’ll come back to that last one. Let’s start at the beginning, with the basic story McCarthy wants to tell. The Counselor is about a drug deal that goes horrifically wrong, mostly because the title character (played by Fassbender; we never learn the guy’s name), who’s never done this before and just wants to make some quick cash, has not the slightest clue what he’s doing. That’s essentially all you need to know, as far as making sense of events is concerned. McCarthy lays out some essential details—how the drugs are transported, and by whom, and who’s looking for a way to intercept the shipment—but only in the service of making it clear that what befalls the counselor is to some degree just very bad luck. What matters is that he was completely unprepared for the possibility that some random misfortune could cost multiple people their lives. Indeed, even the characters, like Brad Pitt’s Westray, who consider themselves prepared, and keep warning the counselor that he’s unprepared, are not themselves really prepared.

Think for a moment about Jurassic Park. In the grand scheme of things, it doesn’t much matter exactly why the dinosaurs get loose—that Wayne Knight’s programmer was planning to steal embryos, and that he got killed by a dinosaur in the attempt, and that his death left the fences unelectrified, and etc. It could just as easily have been some other series of seemingly random deviations from expected outcomes. (Indeed, Ian Malcolm, the chaos theory-obsessed mathematician played by Jeff Goldblum, would argue that it surely would have been.) Jurassic Park is a simple tale of hubris: Various smart people foolishly imagine that they can control the uncontrollable, but something utterly unforeseen occurs, and all hell breaks loose. Nobody complains that the chain of events leading to disaster is overly complicated, because it’s all just a means of providing the exciting sequences of people being menaced by dinosaurs that we want to see.

The Counselor is basically the same movie, aimed at a different sensibility—one that doesn’t necessarily require some of the threatened characters to be sympathetic, and that appreciates a more detached approach to carnage. About halfway through the movie, a man about whom we know nothing shows up at a motorcycle dealership, waves off the salesperson, and proceeds to measure the height of a particular bike. For those on the right wavelength, curiosity about this anonymous character’s purpose is its own reward, and the gruesome payoff constitutes just as much “fun” as does watching a dude cowering on a toilet get chomped by a Tyrannosaurus rex. It’s not even wholly clear to me why the latter is almost universally perceived as entertainment, while the former got widely dismissed as empty grotesquerie. Both involve a benignly sadistic voyeurism that’s always been at the core of the moviegoing experience.

Granted, The Counselor’s nihilism might be less off-putting to many if the characters didn’t keep openly discussing it, often in speeches that occupy several minutes of screen time. (And that’s after they’ve been trimmed—the unrated extended cut of the film, available on the Blu-ray release, runs an extra 21 minutes, with most of that consisting of additional monologue.) This is a natural reaction, as most screenwriters would hesitate to include even one such blatant exegesis in a screenplay, much less a baker’s dozen of ‘em. There’s something strangely liberating, though, about seeing this dramaturgical rule violated with such gleeful excess. Almost every character in The Counselor, including those who drop in for just a scene or two, is ludicrously verbose, prone to bloviating. The first couple of times, it’s a weird distraction; by the end, it’s become an even weirder form of gallows humor. How many different ways can this movie’s pitiless thesis be openly analyzed by the very people who are doomed to be spared its pity?

If McCarthy were Joe Eszterhas, sure, it’d be a problem. But the speeches are beautifully written and performed, and the ordinary give-and-take dialogue is even better. There are admittedly some howlers, like Malkina, the femme fatale, being asked if she’s really that cold (emotionally) and replying “Truth has no temperature.” (Though even that line might have worked with a different actor; I’ll get to Diaz shortly.) The stuff that makes me cringe is handily outweighed, however, by the stuff that makes me chortle.

“Is this place secure?”

“Who knows? I don’t speak in arraignable phrases anywhere.”“I want to give her a diamond so big she’ll be afraid to wear it.”

“She’s probably more courageous than you imagine.”“Cheers.”

“A plague of pustulent boils upon all their scurvid asses.”

“Is that your normal toast?”

“Increasingly.”

As far as I can determine, McCarthy invented the adjective “scurvid,” but it sounds suitably noxious. In any case, the notion that a movie chock-full of pungent exchanges like these offers nothing of value is absurd. Certainly the actors relish them. Pitt, who’s usually at his best when he goes over the top (Twelve Monkeys, Burn After Reading), finds just the right degree of languid sangfroid for his cautious middleman, and Bardem turns in a performance as amusingly eccentric as the wardrobe his character sports. The one weak link is Diaz, for whom Malkina’s predatory nature proves just too much of a stretch. (It doesn’t help that she reportedly performed the role with a Bajan accent, then was asked to overdub it.) The infamous scene in which Malkina intimidates Bardem’s Reiner by rubbing herself against the windshield of his Ferrari was always meant to be ludicrous—although McCarthy’s screenplay conceived it entirely as a story that Reiner tells the counselor, not something that we’re meant to actually see. With Diaz visibly straining to look depraved, it comes across even sillier than was intended; imagine Charlize Theron in her place, and see if it doesn’t suddenly shift into focus, along with the rest of Malkina’s presence in the movie.

Even with these undeniable flaws, McCarthy’s offbeat vision for the movie survives mostly intact. Scott wisely stays out of his way, choosing to serve the text, though he declines to indulge some of the screenplay’s most experimental ideas. The opening scene, for example, depicting the counselor and his girlfriend (Cruz) in bed, begins with the two of them hidden entirely beneath white sheets, suggesting two corpses. As scripted, they were supposed to remain hidden from view the entire time, for what was originally going to be six or seven minutes. What’s more, McCarthy specifies that all their dialogue should be subtitled, despite being spoken in English, as it’ll be too muffled to hear. (Said dialogue is also considerably more blue in its original form.) The decision to shoot the scene more conventionally seems perfectly defensible, but I do wonder whether the more extreme version McCarthy intended might have at least helped to signal that The Counselor doesn’t operate like a traditional thriller. Its subsequent discursiveness and single-mindedness wouldn’t have seemed so thoroughly out of character.

Ultimately, what made this film an object of ridicule—see also everything from Ishtar to Drive—is the enormous gap between the size of the audience it courted and the size of the audience predisposed to appreciate it. Not many people would salivate at a description like “what you might get if you gene-spliced a slow-motion multi-car accident with a freshman comparative philosophy seminar.” (That’s not from a negative review—it’s my own best précis.) But not every movie needs to appeal to every taste. And a movie that makes a lot of folks mad is always more interesting than a movie that makes everyone shrug.