The Amazing Adventures of Mel Gibson, Action Director By Noel Murray

By Yasmina Tawil

When Mel Gibson’s Braveheart won Academy Awards for Best Picture and Best Director in 1996, longtime Oscar historians registered the victories as easily explained and largely insignificant. They were partly the product of an organized and depressingly reactionary fan campaign, and partly due to Hollywood’s tendency to reward both expensive epics and actors who step behind the camera. In the two decades since, Gibson has suffered through personal scandals, and highly publicized controversies over his subsequent directorial efforts The Passion of the Christ and Apocalypto. Given all that, and given that 1996 was also the year of Toy Story, Before Sunrise, Exotica, 12 Monkeys, Apollo 13, Sense And Sensibility, Seven, Safe, Heat, Casino, Crumb, and Babe, the Braveheart triumph today looks all the more hollow.

Or does it? Compared to the more cutting-edge and culturally significant films released in the mid-‘90s, Braveheart does seem like a fluky anomaly: an entertaining throwback that was inexplicably elevated to “Greatest Of All Time” status. But the film is also fascinating in the context of the directorial career of Mel Gibson—a movie star who’s done some of his best work behind the camera, on films that have yet to get their critical due.

Let’s clarify one thing up front: Of the four movies Gibson’s directed, three are deeply flawed, and only one is a masterpiece. But because 2006’s brilliant Apocalypto is the most recent, it casts a long shadow back over a lot of what came before. In retrospect, it’s as though Gibson had been going through a process of trial and error, working his way toward making a classic.

It was never a straight road. Gibson’s 1993 directorial debut, The Man Without a Face, is a more typical actor-turned-director project: a clumsily earnest melodrama with minimal commercial appeal, which Gibson was allowed to helm only if he agreed to double as the star. He plays a small-town recluse with a charred face and body, who becomes the reluctant mentor to an awkward adolescent (played by Nick Stahl), and then gets accused by the community of being a pedophile. The story—based on an Isabelle Holland novel—is a simple “outsider versus the small-minded” morality play, with the added wrinkle that it’s set in 1968, and the villains are mostly hippie aesthetes and academics. The loner hero, meanwhile, favors discipline and old-fashioned values. (In the book, it’s suggested that he also may actually have had sex with his student, but Gibson and screenwriter Malcolm MacRury don’t take it that far.)

The Man Without a Face is mostly notable for introducing a motif that would dominate the director’s next three films: the image of an exceptional man suffering the abuse of angry mobs and cowardly elites. That’s certainly one of the big reasons for Braveheart’s enduring popularity. Reduced to its essence, Gibson’s Oscar-winning historical epic is just a combination war picture and underdog sports drama, in which an unconventional leader—real-life 13th century Scottish warrior William Wallace—trains an outmanned, overpowered squad to fight against a juggernaut. To that, Gibson adds the idea of Wallace as a Christ-like martyr, who gets betrayed by his own people and tortured by the English, suffering so nobly that he rallies others to his cause. The large-scale battle scenes are meant to be more than just thrilling; they’re pinned to the greater cause of “freedom.”

Braveheart’s subtext lies so close to the surface that at times it’s all that the viewer can see. Nevertheless, Gibson took an even blunter approach with 2004’s The Passion of the Christ, which offers a gruelingly brutal depiction of Jesus’ arrest, trial, torture, and crucifixion, lightened only slightly by occasional flashbacks to his life and ministry. Back in 1988, Martin Scorsese enraged some evangelical Christians with an adaptation of Nikos Kazantzakis’ novel The Last Temptation Of Christ that even one of Scorsese’s spiritual advisors referred to as “too much Good Friday, not enough Easter Sunday.” Gibson’s gory Passion Play, though, won the favor of fundamentalists, who pushed their congregations to see The Passion and helped drive its global box office take to a staggering $600 million—nearly triple that of Braveheart, with half the budget.

Gibson’s reputation as a filmmaker has been both boosted and hampered by the ferventness of his supporters. Entering awards season at the end of 1995, Braveheart was seen as a long-shot for anything but technical trophies, but a loud contingent of Braveheart-lovers took to the internet and to radio talk shows to argue that only in depraved, liberal Hollywood would an achievement as remarkable and populist as this film go unrecognized. So when the movie did win its Oscars, the victories were somewhat tainted by the perception that the industry had been bullied into proving its fair-mindedness—even though the more likely explanation was that the town’s old guard loved the picture’s classicism and emotional swells. The huge box office for The Passion was another case where what should’ve been a triumphant narrative had to compete with an alternate story: the one where right-wing Christians rallied around a difficult film in order to play their part in the culture wars.

Neither Braveheart nor The Passion Of The Christ is as accomplished as its devotees contend, or as mediocre as its detractors insist. At nearly three hours, Braveheart is needlessly long, extended by many sequences of the heroes riding and fighting in slow-motion. Passion is an hour shorter but feels longer, because Gibson uses slo-mo even more, and because there’s much, much less plot. Both films are far from subtle in their depiction of villainy, with Braveheart making its bad guys either thuggish or mincing (or both), and Passion emphasizing the ornate clothing and cynical attitudes of its Jewish leaders. When both films were released, Gibson was accused of being homophobic and antisemitic; and whatever his intent, what he put on the screen allows for the worst possible interpretation. Gibson’s history of making appalling statements about gays, Jews, and women—often while under the influence of alcohol—hasn’t made skeptics any more inclined to be forgiving, even now.

Still, there’s a clarity to Gibson’s storytelling that’s incredibly appealing. The Passion Of The Christ is grueling—and even boring at times—but there’s nothing muddled about it. The frequent shots of oppressive crowds and the close-ups of Romans casually manhandling their physically anguished prisoner keeps the audience focused on the suffering and public humiliation. Even when Jesus is locking eyes with strange demon-babies, there’s never any confusion about what’s happening and why. And while it doesn’t happen often enough, in the flashback sequences Gibson and his star Jim Caviezel do a fine job of making Jesus seem warm, generous, and good-humored.

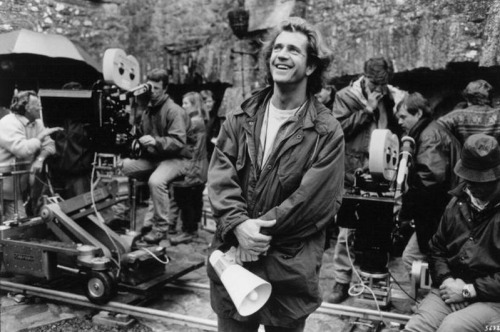

Braveheart’s even better at making an outsized heroic saga seem down-to-earth. In the DVD commentary track, Gibson talks about how he was drawn to Randall Wallace’s script because even during the battle scenes, there are moments of comic relief. He also describes how he could picture the movie as he was reading the screenplay, which is how he knew he should direct it. Taking his cues from his Australian friends and mentors George Miller and Peter Weir, Gibson took pains to make the action sequences kinetic, inventive, varied, and—above all—easy to follow. Whatever Braveheart’s weaknesses as history (which Gibson himself admits has been heavily fudged to make a better story) and as drama, it’s a master class in how to work on a large scale. Even with thousands of extras and hundreds of horses, the frame is never too cluttered to know where to look. The director—along with cinematographer John Toll and editor Steven Rosenblum—guide the eye to the ever-changing, cool-looking handmade weapons and traps that the heroes use.

It shouldn’t be overlooked how daring, distinctive, and clearly personal Gibson’s films have been. Braveheart may have seemed like a safe choice for the Academy by the time it won Best Picture, but at the time it was made, it was hardly a good bet to spend $70 million on a movie with the scope of Spartacus and the rawness of an early ‘80s Ozploitation picture. There were also much easier choices that Gibson could’ve made with The Passion Of The Christ besides having it be so slow-paced and bloody (and in a foreign language, no less). Gibson has crowd-pleasing instincts, but can’t seem to stop himself from lingering over pain and sacrifice until his audience starts to squirm.

Which brings us back to Apocalypto, the film where Gibson has made the best use of everything he’s learned. Much as The Passion Of The Christ is meant to feel intimate and immediate, Apocalypto aims to plunge the viewer into an intense scenario, in an exotic locale. Gibson and his co-screenwriter Farhad Safinia have said the film was inspired by two ideas they’d batted around together: to make a movie that was essentially one long foot-chase, and to tell a story in the ancient world where the real enemy is something that the chasers and the chased alike never see coming.

Apocalypto actually doesn’t get to its chase for almost an hour—which is the film’s one real flaw, that it dawdles in the early going. In the well-crafted opening, Gibson introduces a 16th century Meso-American tribesman named Jaguar Paw (played by Rudy Youngblood), and gives a little taste of the satisfyingly primal life of a hunter-gatherer and his family. Once again, Gibson interjects humor and playfulness, while establishing the dangers and parameters of the rainforest. Then Jaguar Paw’s village is raided, and his people enslaved—in a sequence that’s excessively violent and overlong, in Gibson’s usual way—leading to a long march in chains to a Mayan city. Gradually, the film picks up momentum as the new slaves work their way through swift shoulder-deep rivers, and past falling trees and pockets of pestilence.

When Jaguar Paw and his tribe arrive at a tall pyramid with steep stairs (an enormous practical set, built for the movie), they witness a spectacle of dance and human sacrifice that’s supposed to end in some of their deaths. But through a series of chance occurrences, the hero gets one last opportunity to run for his life—all while his pregnant wife and son are trying to figure out how to escape from a slowly flooding cave. Once Jaguar Paw gets deep enough into the wilderness, he uses his knowledge of the land and its many natural horrors to fight off the dozens of men coming after him.

There’s almost no dialogue in Apocalypto—and not much in the way of exposition, either. Here’s what the movie does have: a jungle cat eating a man’s face off; tumblers doing a choreographed dance that ends with them catching severed heads in a basket; a hail of arrows that impales one target through the back of his head and mouth; live ants being used to suture an open wound; a jump off a waterfall that ends with one jumper smashing his head against the rocks below; a beehive used as a makeshift bomb; an attacking monkey fended off with a stalactite; and more.

Gibson and Safinia load up on both the extreme gore and pageantry of The Passion of the Christ and the clever guerrilla warfare of Braveheart, in ways that they admit on the commentary track aren’t always historically accurate. Their intent was to dazzle, disgust, shock, and captivate, creating a visceral experience. Apocalypyto isn’t devoid of Gibson’s recurring “one savvy warrior against the mediocre masses” theme, but this film is more about pure visual dynamism: logistically tricky crane shots and dramatic low angles, for their own sake. When Jaguar Paw tumbles down a mountain of human corpses, it’s like something out of Jodorowsky or Pasolini film, but popped into the middle of a Mad Max pre-pre-prequel.

Post-Apocalypto, Gibson has reduced his workload significantly both in front of and behind the camera, in large part because 2006 was the year when some of his most embarrassing personal scandals flared up (and, arguably, kept his best movie from getting properly hailed). He’s acted in a half-dozen movies in the past 12 years, and he’s currently working on his next film as a director: the World War II picture Hacksaw Ridge, with a script partially written by Braveheart’s Wallace.

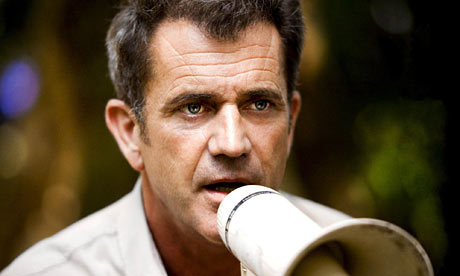

When Hacksaw Ridge comes out later this year, it’s highly likely that a lot of the old debates about Gibson will resurface. Does his messy personal life matter when it comes to assessing his work? Do his films shamelessly stoke the bloodlust and martyr complexes of some of his most steadfast defenders? Or is he a skilled craftsman with keen commercial instincts, whose critical reputation has been affected by bias and bad timing?

In the years since Apocalypto, more film buffs have been coming around to the latter view, so don’t be surprised if Gibson starts to experience a Clint Eastwood-like turnaround from cinephiles who are squeamish about the director’s politics but can’t deny his gifts. Time and perspective have a way of smoothing out the rockier patches of an artist’s biography—as anyone who’s ever read about the drunken debauchery of their favorite long-dead filmmaker or writer or musician can attest. The balance also shifts every time that artist creates something new. It’s hard to do much with a single piece of work, in isolation. Add to it though, and film by film, a body takes shape—strong enough to withstand any punishment.