Truly Inconvenient Truths: ‘The Island President’ and “Issue Doc” Aesthetics By Andrew Lapin

By Yasmina Tawil

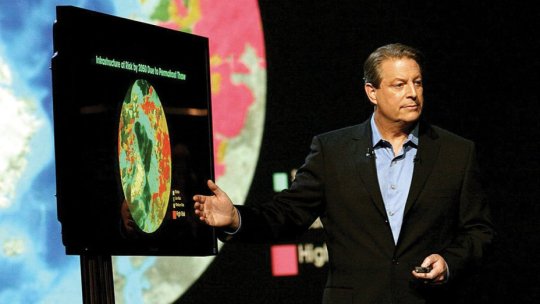

We like to say that documentaries can change the world. But the manner in which they change it matters. Ten years ago, when Davis Guggenheim’s An Inconvenient Truth sounded the alarm bells on man-made climate change, its aesthetic mission was clear: Al Gore, on a stage, flipping through slides.

An Inconvenient Truth wasn’t trying to be a movie, at least not in the way we were used to seeing one. This was information, delivered in as no-frills a manner as possible, and distributed via movie theater. But it was valuable information, and that made the film culturally significant, a world-changer. An Inconvenient Truth grossed nearly $50 million worldwide, won two Oscars, and was instrumental in convincing millions of people around the globe of the urgent threat to our planet. It spawned dozens of imitators, “issue docs” that used a lot of charts and graphs to get a point across.

“We have everything that we need to reduce carbon emissions, everything except political will,” Gore says at the film’s conclusion. In what would become standard procedure for all documentaries distributed by Participant Media, the end credits came packaged with a list of things you, the viewer, can do to help: recycle, drive hybrids, and, of course, get other people to watch An Inconvenient Truth.

But is this style really the best way to communicate pertinent issues to the masses? I’m talking about cinematic value here, but I’m also talking about the way humans absorb information. Our very human-ness compels us to crave more than facts on a screen. We need narrative, characters, scope, stakes, and indelible images, laced with a touch of humor and a whole lot of pathos. We need, in short, cinema.

Jon Shenk’s 2011 documentary The Island President is the climate change movie we need right now, and from a stylistic viewpoint, it’s the “issue doc” other filmmakers should cherish. On the surface, it carries a similar structure to Guggenheim’s film, in that it gives us an intimate portrait of an idealistic politician trying to warn the world about the dangers of fossil fuel consumption. The difference is in its operatic tone and execution, and in the underlying, pervasive sense of futility. The titular island president lives on both a physical and figurative island, as he’s woefully overmatched against both the natural and human forces that will ultimately destroy his home.

Our hero is Mohamed Nasheed, who, once upon a time, was president of the Maldives. While he was in power from 2008-12, Nasheed made climate change his top priority, due to the fact that his low-lying country of 26 atolls is literally being washed away by rising sea levels. (Research differs on whether the islands themselves can adapt to higher tides, but not on whether developed, industrialized land can survive. It can’t.)

The genius of the film is that it’s not solely concerned with environmental alarmism. How Nasheed ascended to power, how he became a leading global voice from such a relatively tiny platform, how squabbling with much bigger countries over fossil fuels nearly broke him, and how he was eventually ousted from his position is the stuff of a great narrative arc. It’s the story Shenk embraces, via a mix of documentary techniques that keep the audience from growing too comfortable.

In fact, for a good chunk of the film’s early third, we barely hear about climate change at all. We instead move through recent Maldivian history at a briskly edited clip, a style familiar to fans of recent no-nonsense biographical docs like Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry. We see how Nasheed was drawn to political activism from an early age and how the government imprisoned him for writing opposition articles. We see how he journeyed in and out of jail for years, building outcry from the international community, and left the country briefly in exile, until he had finally amassed enough populist support to power his way into top office in the country’s first democratically held elections: a small victory over human conflicts that would foreshadow a much tougher losing battle against the forces of nature.

Even as we are moved by the Island West Wing optimism of Nasheed’s ascent, how it seems to affirm the strength of the democratic process for even the smallest of nations, Shenk gives us hints that not all is well. On Malé, the country’s heavily industrialized capital city, buildings teeter like Jenga blocks on a land mass only a few feet from the water. Waves crash onto the rocks at the shoreline with jarring, violent force, and Shenk places the camera right there, on the edge of the world, so close we hold our collective breath when the water comes rolling in.

After the first act has unspooled, documentary veterans would expect to stick to the same format for the duration of the film. The problem is that a tripod-and-talking-head approach implies there’s a safety net, that the story unfolding is a complete one, that everything that needed to happen has already happened, and that the director now has the luxury of assembling the best moments in the editing room. But Nasheed’s story is not complete, and when Shenk began shadowing him in the lead-up to the 2009 Copenhagen Climate Summit, the events were too urgent to pair with distant expert reflection.

So once Nasheed is in power, Shenk frees himself from the tripod, because there’s no longer any assured way to tell this story. Instead, there are quiet sequences where the camera follows Nasheed walking through a variety of situations. He meets with officials on the edge of Malé where they point out 300 feet of eroded land, wanders ghost-like through his own house before dinner, even suits up in his hotel room before major public appearances.

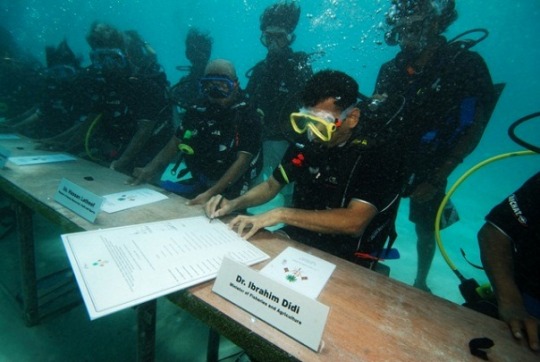

It’s worth noting that we’re not dealing with a Weiner here. Nasheed granted Shenk such access because he’s a master of publicity, just as he staged the world’s first “underwater press conference” because he knew the absurdity of such an image would resonate with the global media. Though we cannot know for sure, there’s probably never a moment in the film when he’s genuinely unguarded. Yet this doesn’t change the fact that such a level of physical intimacy is astounding and, to my knowledge, unprecedented for any documentary about a sitting head of state. When we overhear Nasheed gripe to his staff, frustrated by inaction after a gathering of small island nations, we understand with full hearts the uncertainty of what he is doing: how little power he wields relative to the truly powerful, and how desperate he is to attract attention to a doomed cause.

We only realize the grand tragedy of Nasheed’s efforts in the second half, when Shenk follows him on an epic global jaunt to raise awareness of his country’s imminent end. There are stops in New York, London, and New Delhi before the climactic negotiations at Copenhagen, during which we witness the world opening up to Nasheed, in a poignant and painful way. Many scientists agree that a carbon emissions cap of 350 parts per million is the absolute maximum threshold that can halt further catastrophic damage to the planet, yet intransigent representatives from China and India refuse to commit to the number. We glimpse the truly powerful figures, like President Obama, only from a distance, and even once an agreement is reached, a postscript reminds us that global emissions levels still hover far above the target. The footage of Nasheed being dwarfed by this challenge is like a splash of saltwater in the eyes: Trying to wean the world superpowers off carbon emissions is as fruitless as trying to stop the ocean waves from lapping ashore the Maldives.

For Nasheed, pushing his own country toward representative democracy was the easy part. And, as a brief title card during the epilogue confirms, even that wasn’t so easy. The president was ousted from his position under very coup-like circumstances and re-imprisoned shortly after filming wrapped, only recently escaping to exile in the U.K., with help from none other than Amal Clooney. “What’s the point of having a conflict when we’re all going to die anyway?” Nasheed muses in the film, before history repeats itself.

It’s unfortunate that all this happened after filming wrapped, as it means The Island President wasn’t able to capture the totality of Nasheed’s arc. This leaves the movie marooned on the Island Of Documentaries That Didn’t Get The Whole Story—alongside such company as Being Elmo, the 2011 film about Kevin Clash made before public airing of the sex abuse allegations that would end his career, and the aforementioned Never Sorry, which ended before key developments in Ai Weiwei’s ongoing battle with the Chinese government could unfold.

But Shenk’s film, despite the regrettable omissions, is not a footnote. It captures a moment in the world of high-stakes climate negotiations that demonstrates, through intelligent filmmaking decisions, just how hard it is to actually affect change in the world. Turns out it’s a far more inconvenient process than simply telling friends about a movie. A closing montage pairs aerial footage of the Maldives, lush and green and naked before the world, with Radiohead’s “How to Disappear Completely.” It should be too obvious to work, and yet the lyrics (“I’m not here/ This isn’t happening”) perfectly underscore the theme of collective denial in the face of a tiny country’s mammoth struggle.

The film’s greatest irony is that, by giving us less world-changing goodness to latch onto, it communicates the need to change far more urgently than any other documentary before or since. If anything is going to save the world in our dark and uncertain times, it just might be the power of narrative.