The Cat Who Won’t Cop Out: Shaft as the ‘70s Black Superhero

By Yasmina Tawil

(The following essay is excerpt from Jason’s new book, It’s Okay With Me: Hollywood, the 1970s, and the Return of the Private Eye.)

The first thing John Shaft (Richard Roundtree) does in Gordon Parks’ Shaft, after emerging from a Times Square subway station below the grindhouse movie theaters that would eventually and enthusiastically screen his adventures, is walk into New York City traffic (Shaft can’t be stopped, even by Eighth Avenue) and flip off the driver who gets too close to him. Meet your new action hero, Middle America; here is his message to you.

Shaft came early in the so-called “blaxpoitation” movement—a period, running roughly from 1970 to 1975, that saw an explosion of films made for, about, and often by African-Americans. This was an underserved audience; with the exception of independent “race picture” makers like Oscar Micheaux and Spencer Williams, their stories simply weren’t told onscreen, and they certainly weren’t told by mainstream studio films, which consigned black performers to subservient roles (or worse). The winds started to shift in the 1960s, when Sidney Poitier became a bankable name and Oscar-winning star, but he was the exception to the rule. It wasn’t until football star-turned-actor Jim Brown leveraged his supporting turn in the 1967 smash The Dirty Dozen into bona fide action hero status that this untapped swath of moviegoers, hungry for entertainment and representation, began to make itself known.

1970 saw the release of two very big (and very different) hits: Ossie Davis’ high-spirited crime comedy Cotton Comes to Harlem, and Melvin Van Peebles’ provocative, X-rated (“by an all-white jury!” boasted the ads) Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song. Peebles’ film was, essentially, the black Easy Rider, a rough-edged road movie with a decidedly European sensibility that grossed something like $15 million on a $150K budget, a return on investment so huge, the (flailing) studios couldn’t help but take notice.

Shaft was next down the chute. Adapted by Ernest Tidyman—who also wrote that year’s Best Picture winner The French Connection—from his 1970 novel, the film was helmed by Gordon Parks, the influential photographer who’d made his directorial debut in 1969 with the autobiographical The Learning Tree. MGM gave him a modest $1 million budget; model-turned-actor Roundtree was paid a mere $13,500 to play the title role. (Isaac Hayes was among the actors who auditioned, and though Parks passed on his acting, he hired Hayes to compose and perform the picture’s iconic funk score.)

“Shaft essentially was a standard white detective tale enlivened by a black sensibility,” wrote Donald Bogle, in his essential Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies, & Bucks. “As Roundtree’s John Shaft—mellow but assertive and unintimidated by whites—bopped through those hot mean streets dressed in his cool leather, he looked to black audiences like a brother they had all seen many times but never on screen.” He’s right on both scores. Shaft, who is smirkingly called a “black Spade detective,” is embroiled in a commonplace private eye narrative, engaged by a lying client (uptown gangster Bumpy Jonas, smoothly played by Moses Gunn) to find a missing girl—in this case, the client’s daughter. Shaft is a snappy dresser and sharp shooter; he uses the neighborhood bar as his second office.

But we’ve never seen a private eye who looks like this. Shaft leaves the shirts and ties to the cops and gangsters; he wears turtlenecks with his suits, along with that amazing leather coat. In the documentary Baadasssss Cinema, blaxploitation acolyte Quentin Tarantino is critical of the lack of action in Shaft’s opening credit sequence (“I’m semi-frustrated that [the theme] wasn’t utilized better,” he explains. “If I had the theme to Shaft to open up my movie, I’d open my damn movie”), but he’s underestimating the visual jolt of merely showing a man like Shaft strutting the streets of New York, and gazing upon him as he stakes his claim.

There’s something undeniably sensual about that gaze. Shaft was among the first major motion pictures to feature a black man of sexual potency—with the phallic overtones embedded right in his surname, and thus in the film’s title. He gets a full-on sex scene with his steady lady early in the film; later on, he shares a steamy shower with a white pick-up, a mere four years after the carefully sexless interracial romance of Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner.

But aside from that scene—and the iconographically loaded image, during the climax, of black militants turning fire hoses on white people—Shaft’s racial politics are surprisingly middle-of-the-road. Shaft may kid Lt. Vic Androzzi (Charles Cioffi) with lines like “It warms my black heart to see you so concerned for us minority folks,” but he humors the white cop, and mostly cooperates with him. The script is careful to disassociate its fictional black-power revolutionary group from real ones like the Black Panthers and the Young Lords, but it also shows them to be ineffectual, and Shaft is ultimately interested in their manpower, not their politics.

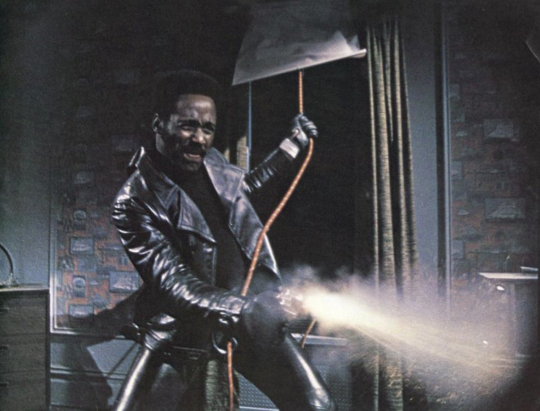

In other words, it’s a film that straddles its lines carefully, just as Shaft must code-switch between worlds: black and white, cop and crook, uptown and downtown (his black gangster client runs Harlem, but Shaft’s office is in midtown and he lives in the Village). Yet when it’s clutch time, Shaft is a full-on badass. In his first fight scene, the unarmed detective takes out two gun-wielding tough guys; in the climax, he swings in through a window like goddamn Batman, the black superhero rescuing the damsel in distress (stolen, not incidentally, by the white man).

Such elements became cornerstones of the blaxpoitation action template. Nelson George, who calls the film “a typical detective flick in blackface,” runs them down in his book Blackface: “black nationalists depicted as inept, if well meaning, supporting characters; young women, of all colors, are sexual pawns or playthings; white and black mobsters are in constant collaboration and conflict.” To that we can add a dash of respectability politics (Bumpy’s daughter is worth saving because she’s a “good girl” who’s “going to college”), righteous condemnation of drug dealing, and black characters working within the system while maintaining (though not without a struggle) their “blackness.”

Audiences ate it up. “Take a formula private-eye plot, update it with all-black environment, and lace with contemporary standards of on-and off-screen violence, and the result is Shaft,” opined Variety, predicting that “Strong B.O. [box office] prospects loom in urban black situations, elsewhere good.“ That was an understatement. Shaft’s $12 million gross helped save MGM, confirmed the audience that Cotton and Sweet Sweetback suggested, and prompted a flurry of imitators, including the following year’s quickie sequel Shaft’s Big Score!

Parks, Tidyman, and Roundtree all returned for the sequel—the latter with a healthy salary bump, to $50,000—though Isaac Hayes only contributed a single new song, turning over composer duties to Parks. Inexplicably, Hayes’ “Theme From Shaft,” which had won an Oscar in the intervening year, is nowhere to be heard, jettisoned in favor of a sequel song by O.C. Smith (and sequels, per usual, aren’t equal), a decision roughly akin to discarding the Bond theme after Dr. No.

It’s not the only questionable call. Instead of Lt. Vic, Shaft’s police foil is a smug black sell-out cop, whom Shaft calls a “black honky with big flat feet” and who is seen telling a black suspect, “Fuck your rights, go sue the city.” Shaft doesn’t really investigate a mystery this time around—the villain is revealed before our hero is, and the script stays that course—and no one actually hires him either. The script merely parachutes him into the middle of another war between Harlem gangs and the Italian mob. Parks was working with a larger budget, but you don’t see it until the third act’s tight car chase, followed by an ace boat/chopper sequence. The filmmakers clearly put their energies into a super-slick Hollywood ending—and it looks great. But they ended up sanding down what made the first film interesting; much of its uniqueness is in its rough edges.

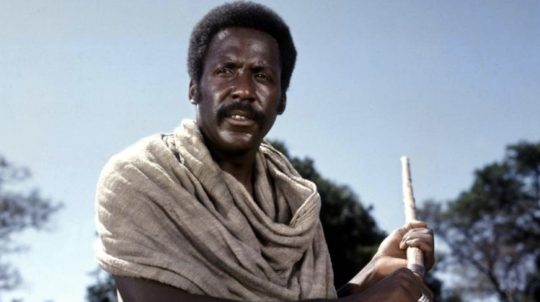

The same goes for Shaft in Africa, which appeared the following year and took that character to the logical conclusion of his savior-warrior construct. Shaft is hired this time to penetrate a modern African slavery ring, and though he is initially resistant to the mission—he says the case is “out of my turf,” since “I don’t know any Africans, brother”—he ends up training and studying to go undercover as a native. Gordon Parks demurred from participating in this third and final installment, and white director John Guillermin (who would next direct The Towering Inferno and the 1976 King Kong remake) is extra careful with his camera placement during Shaft’s nude “stick fight,” but the sexual implications aren’t exactly subtle, and that’s before our hero smirks, “Guy named Shaft ain’t gonna be bad with a stick.” (Finally, someone said it.)

Africa has the broadest and perhaps clumsiest sexual messaging of the trilogy (and that’s putting aside its weird female genital mutilation subplot—don’t ask). Late in the film, our hero is seduced by the arch-villain’s insatiable white mistress, who initially queries, “How long is your phallus, Mr. Shaft,” and later tells him, “You’re the first man who’s ever made love to me the way a man should.” Shaft is, indeed, the private dick, detective as both superhero and super-stud. That scene falls during Shaft and his fellow laborers’ crossing from Africa to Paris, a water journey that’s uncomfortably crowded and dehumanizing, explicitly echoing the Middle Passage—and thus positing Shaft as a racial avenger. He ends up leading what amounts to a slave revolt, an unexpected Shaft-as-Nat-Turner twist, full-on retroactive wish fulfillment.

But wish fulfillment was ultimately what blaxploitation in general, and these films in particular, were all about. Characters like Shaft and Trouble Man’s “Mr. T” don’t do a helluva lot of detecting, per se; they’re more like urban independent cops, allowing their creators to make what amounted to police movies for audiences who didn’t like and didn’t trust police. (When a complicated film like Across 110th Street dealt with those complexities, neither black nor white audiences showed up.)

But the further they got from their mean streets, the less they reflected their day-to-day reality. Reflecting on the power of Shaft in his review of its sequel, the New York Times’ Roger Greenspun noted, “After every sort of big-town white detective from Marlowe to Madigan had obviously lost the freedom of the city, John Shaft—cool, insolent, clever—seemed a fair choice to take their place. For the detective is nothing if not indigenous; the best hero we have to offer, once we know the misery around us and our own despair.” However, “the new Shaft follows a new and glossier and tidier image, an image that is much more James Bond than Bogart.”

The Shaft sequels pivoted from the urban gangster bad guys of the first film to smugly erudite super-villains; Big Score’s plays a clarinet, for God’s sake. By the time he hits Africa, Shaft has to explicitly insist that he’s not James Bond, but it’s an easy conclusion to jump to—the line comes during a gadget briefing sequence, from his own junior varsity Q.

Yet the inclination towards such a character, for filmmakers and audiences, is understandable. In his book More Than Night, James Naremore attributes Parks and Van Peebles’ “black supermen” as a response to “decades of emasculated or nearly invisible black people on the screen,” but there was more at play here than that. By the early 1970s, black heroes were at a premium; Martin was dead and so was Malcolm, Fred Hampton and George Jackson, too, and the black revolutionary movement was scarcely in better shape than in its portrayals in films like Shaft. Eldridge Cleaver and Huey P. Newton’s in-fighting split the Panthers in 1971, and by early ’72, Newton was shutting down chapters—the ones that hadn’t been raided by police. Cleaver was in Algerian exile, and Bobby Seale was in jail. The Panthers had been undone by COINTELPRO, heroin, and ego. “We had the revolution,” Richard Pryor joked in 1976. “Remember the revolution, brother? We lost!”

But on screen, they could win. If he was enough of an outsider—his own boss, beholden to no one—the black man could be a hero. He could mouth off to cops, he could protect the community, he could be irresistible to women. He could come out on top, and truth and justice could prevail; he could do all of the things that white private detectives did back in the 1940s, and didn’t do anymore. When those white counterparts first appeared in the ‘40s, they served a similar function for an audience coming out of a Great Depression, fighting a world war, and uncertain about their future. That audience needed tough, straightforward heroes with an unerring moral compass; so did this one.

The black private eyes didn’t have the luxury, in this tense and uncertain time, of flirting with the existentialism of Hickey and Boggs or The Long Goodbye’s Marlowe or Night Moves’ Harry Moseby. Isaac Hayes may have called Shaft “a complicated man,” but there was nothing complicated about him, or any of his brethren. What you saw was what you got. “He was everything we’d always wanted to be,” said Samuel L. Jackson, who would take over the role of Shaft in a 2000 remake. “He was cool, he talked tough, he looked great, and he was fearless. He was a hero.”

In the ‘70s, black audiences looked at their movie detectives and saw what they wanted to be. White audiences looked at theirs, and saw what they were.