Lie To Me: The Multiple Personalities of Tom Waits Acting Career by Chris Evangelista

By Yasmina Tawil

“I ain’t no extra baby, I’m a leading man.”

— Tom Waits, Goin’ Out West

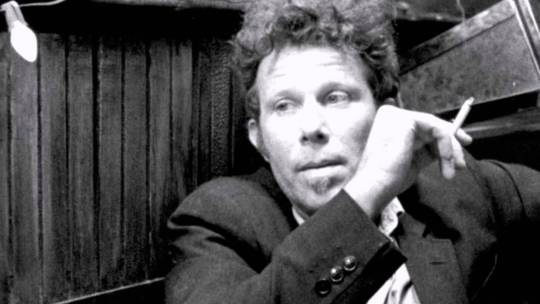

Tom Waits lights up the screen. The minute the singer appears in a film, he brings with him a sort of atmospheric baggage—we may not know what character he’s playing, but we know him. We know that no matter what the film is, Waits will lend his own distinct, off-kilter brand of weirdness to it. Waits has been playing characters all through his musical career, the boozy troubadours and raspy-voiced noir loners who populate his songs are all engaging Waits creations.

Using his distinct, gravel-caked voice, Tom Waits conjures up boozy ballads designed to be played low at 3 a.m. and melodies that might echo off the broken-down rides of an abandoned, haunted carnival. His is an eclectic style, combining blues, jazz, cabaret, Spooky Sounds of Halloween sound effects tapes, and more. This distinct, unmistakable style goes beyond Waits’ musical accomplishments, finding its way into his acting in the two dozen or so film appearances the singer has made.

Waits doesn’t consider himself foremost an actor. “I do some acting,” Waits tells Pitchfork. “And there’s a difference between ‘I do some acting’ and ‘I’m an actor.’ People don’t really trust people to do two things well. If they’re going to spend money, they want to get the guy who’s the best at what he does. Otherwise, it’s like getting one of those business cards that says about eight things on it. I do aromatherapy, yard work, hauling, acupressure. With acting, I usually get people who want to put me in for a short time. Or they have a really odd part that only has two pages of dialogue, if that.”

Waits’ first film appearance was in Sylvester Stallone’s 1978 directorial debut Paradise Alley. It’s a small part, with Waits essentially playing a version of himself, or at least the self he presents in many of his songs. The character, Mumbles, shows up at a piano, twitching and crooning. “When was the last time you was with a woman?” Stallone’s character asks him. “Probably before the depression,” Mumbles says. “What are you saving it for?” Stallone shoots back in that garbled manner of speaking Stallone has perfected. “I dunno,” Waits replies. “Probably a big finish.”

In the grand scheme of things, this is a nothing part; it was intended to be a bigger role, but Stallone cut it down to little more than a cameo. Yet what made it to the screen is distinct because Waits makes it so. Stallone is very still in the scene, leaning on Waits’ piano like dead weight. Waits is a study in contrast, never sitting still, his eyes half open. It might even be considered too much acting. When asked if acting came naturally to him, Waits replied, “It’s a lot of work to try and be natural, like trying to catch a bullet in your teeth.”

Waits’ career was at an all-time-low following 1978. He had grown tired of the music industry in general, having released six albums with very little commercial success. Battling depression and alcoholism, Waits left Los Angeles for New York and began a period of reinvention. “I just got totally disenchanted with the music business,” he would say. “I moved to New York and was seriously considering other possible career alternatives…the whole Modus Operandi of sitting down and writing, and making an album, going out on the road with a band. Away for three months, come back with high blood pressure, a drinking problem, tuberculosis, a warped sense of humor. It just became predictable.”

Waits’ music became more avant-garde, more eclectic. And his film career and personal life took a distinct turn in the 1980s. In 1982, Francis Ford Coppola hired Waits to write the music for One From the Heart, a romantic fable that Coppola wanted to make as a sort of palate cleanser following the troubled production of Apocalypse Now.

“I looked forward to the challenge,” Waits said. “I needed something to stimulate my growth and development. The sole process of making music that would adhere to film was still something new to me. So it was a little terrifying. But working with Francis seemed like a good opportunity.”

It was on the set of One From the Heart that Waits would begin his relationship with future wife and musical collaborator Kathleen Brennan, who worked as a script analyst for the film. The two had previously met at a New Year’s Eve Party, but it was during One From the Heart that the relationship blossomed. “She was a story analyst. Somebody told her to go down and knock on my door and she did and I opened the door and there she was and that was it,” Waits said. “That was it for me. Love at first sight. Love at second sight.“

One From the Heart would be a financial disaster for Coppola, but Waits and the filmmaker continued to collaborate. Coppola would cast Waits in small parts in his back-to-back S.E. Hinton adaptations The Outsiders (“I had one line: ‘What is it you boys want?’” Waits told Rolling Stone in 1988. “I still have it down if they need me to go back and re-create the scene for any reason.”) and Rumble Fish (“got a chance to pick out my own costume and write my own dialogue. Gotta nice scene with a clock.”)

Little by little, Waits was building a bit-part filmography, showing up in the background of films and stealing the show with little to no dialogue, catching the eye with his lanky frame and coiffed hair. Coppola would cast Waits again in 1984’s The Cotton Club. Waits plays the club’s MC, but most of his scenes were cut from a film that became more and more bloated during production.

Waits’ first big role would come courtesy of Jim Jarmusch’s 1986 Down by Law. Set in Louisiana, the film follows three convicts—John Lurie, Roberto Benigni and Waits—who escape into the bayou. Once again, Waits seems to be playing a variation of himself, or the self that he built through his musical career, although he insisted the character not be a musician. Instead, he’s a DJ. Waits’ inaugural scene kicks off with him creeping into his bedroom, trying hard not to wake up his sleeping girlfriend, played by Ellen Barkin. But Barkin’s character isn’t really asleep, and when we next see these two characters, she’s tossing Wait’s belongings out of their New Orleans apartment, disgusted with his philandering.

Waits spends the scene sitting on the bed, mostly silent as Barkin rages, tossing one vinyl record after another and hurling curses at Waits. Waits doesn’t fully spring into action until Barkin is about to toss his clunky, pointed, steel-tipped shoes. “Not the shoes!” he protests, sounding generally horrified. Later, he sits at the curb, his possessions scattered around him, slipping those shoes on. It is an overall commanding performance, illustrating that simple cameo appearances from the singer, while memorable, waste his natural hipster charisma. To put it simply, Waits is cool—the type of old-school cool that would likely come off as posturing if you caught someone trying it in public. Yet Waits makes it sing. His characters are perhaps never as cool as they think they are, yet the coolness is undeniable. These are the types of performances people want to emulate when young. You look at Waits’ ridiculous Frankenstein shoes in Down by Law and briefly think, “Where can I get a pair of those?”

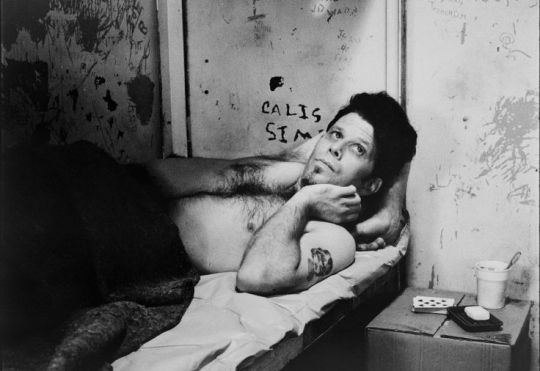

In the somber, autumnal Ironweed, Waits plays Rudy, the physical embodiment of every boozy balladeer Waits has ever sung about, particularly in “The Piano Has Been Drinking.” (“And you can’t find your waitress with a Geiger counter/ And she hates you and your friends and you just can’t get served without her.”)

“I have a red nose, and I had a toothbrush in one pocket, a sandwich in the other. I don’t know why I got it, but I’m glad I did,” Waits said. The part found him playing alongside acting giants Jack Nicholson and Meryl Streep. “Nicholson is really a diamond cutter,” Waits said. “He’s a bank president and a bronc rider. He has a million stories; all of them are true. He’s a very generous actor, and he’s responsive, like a good musician.” The pair play off each other beautifully, with Waits not just holding his own alongside Nicholson but occasionally outshining him.

“At rehearsals, Tom Waits looked like any moment he might break at the waist or his head might fall off his shoulders onto the floor,” Nicholson said. “I once saw a small-town idiot walking across the park, totally drunk, but he was holding an ice cream, staggering, but also concentrating on not allowing the ice cream to fall. I felt there was something similar in Tom.”

Waits, who eventually would go to AA and get sober, likely was able to draw on his own alcoholism for the role. “[O]ne is never completely certain when you drink and do drugs whether the spirits that are moving through you are the spirits from the bottle or your own,” he told The Guardian. “And, at a certain point, you become afraid of the answer. That’s one of the biggest things that keeps people from getting sober, they’re afraid to find out that it was the liquor talking all along…I was trying to prove something to myself, too. It was like, ‘Am I genuinely eccentric? Or am I just wearing a funny hat?’”

At this point, Waits began to become highly sought after for film work. He would continue to take on eclectic, eccentric parts, like as a rough-and-tumble bush pilot in the 1991 drama At Play In the Fields of The Lord and an uncredited role as a disabled veteran in Terry Gilliam’s The Fisher King. “He was a friend of Jeff Bridges, basically,” Gilliam said. “[Bridges] said, ‘You ought to meet Tom.’ It’s funny because when I met him and even in the course of making the film, I’d never heard a Tom Waits record. I’d never listened to them at all. I just met him and liked him immediately. So into the film he went, and he was great. The studio was trying to cut him out. They felt it wasn’t advancing the narrative in any significant way so they thought that was things that could go. They were totally wrong.”

In 1992, Francis Ford Coppola made a play to save his struggling American Zoetrope studio with a lush adaptation of Bram Stoker’s Dracula. The gothic costume drama gave Coppola and Waits an excuse to work together again, with Waits taking on the role of bug-eating madman Renfield. It was a distinctly un-cool part for Waits, yet he manages to steal almost every scene he’s in. He rants, he raves, he wears bizarre metal devices on his hands. Yet there’s a distinct humanity underneath the over-the-top madness, such as a scene where Waits’ Renfield disobeys his master Dracula to warn Winona Ryder’s Mina that she’s in danger. “Got to have a really meaningful scene with Winona Ryder. Not how I imagined it would be, though. Bug juice dripping from the corners of my mouth. Unshaven. Totally gray. Screaming behind bars. Not how I saw our scene together. But I tried to rise above it,” he told Image magazine.

At this point in his career, Waits was aging gracefully beyond his hipster youth into his 40s, in a sense turning into the older-seeming, more lived-in man his songs portrayed. In Robert Altman’s 1993 Short Cuts, adapted from the works of Raymond Carver, Waits plays a washed-up version of the younger, cooler individuals he had excelled at. He’s aging, alcoholic limo driver Earl, married to waitress Doreen (Lily Tomlin). “He seemed like someone I knew very well on a soul level,” Tomlin told The A.V. Club. “We did one thing I recall that would never read on camera: We ‘tattooed’ on our hands, at the base of the right thumb, the image of half a heart and when I’d pass him at the counter, we’d touch that part of each hand to the other and he’d say under his breath, ‘’Til the wheels come off.’” Waits also went method for the role, according to Tomlin: “Tom called me the first night after shooting, in his character of ‘Earl’ and spent maybe half an hour talking to me as ‘Doreen,’ as he supposedly drove around in the limo, which was Earl’s job. Tom did that for two or three more nights after work. Thinking he’d never do it again, I never was prepared to tape him and, each time he called, he was nothing if not filled with poetry as Earl.”

From there, Waits’ roles only grew more and more bizarre. He had wondered, “Am I genuinely eccentric? Or am I just wearing a funny hat?” around the time he quit drinking, but now he seemed to be firmly entering the “funny hat” zone of his acting career. In Mystery Men, he plays an inventor of non-lethal weapons who spends his free time trying to pick up women at nursing homes; in Domino, he appears as an exposition-dumping character known only as the Wanderer; Wristcutters: A Love Story finds him as commune leader in the afterlife; The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus reunited him with Terry Gilliam again to play the devil himself; and Seven Psychopaths had him playing a serial killer who loves rabbits.

The older Waits gets, the more he seems comfortable playing such wild weirdos. Perhaps he’s always been comfortable growing into that weirdness. Waits’ musical career was filled with sea change. He went from the lonely-heart, tears-in-my-beer crooning of his earlier albums to the banging-on-a-trashcan hullabaloo of 1983’s Swordfishtrombones. In 1999, Waits released Mule Variations, an album that, according to Rolling Stone, “rounded up his multiple personalities—barfly poet, avant-garde storyteller, family guy” into one place. Those multiple personalities spilled over into his acting career as well.

Waits is known for intriguing and eccentric choices as a musician —and that’s a recognition that should bleed over into his acting career. “I think most singers, when they start out, are doing really bad impersonations of other singers that they admire,” Waits once told NPR. “You kind of evolve into your voice. Or maybe your voice is out there, waiting for you to grow up.” For Waits, changing and evolving was like second nature. “The person that I saw changed every year,” said music producer and Waits friend Dayton “Bones” Howe. “His philosophy was, if I keep being a moving target, I can’t get hit. He never wanted to be the same again in any way.”