Sleuthing in the 70s: The Long Goodbye,Chinatown, and Night Moves bySteven Goldman

By Yasmina Tawil

Theres a body on the railing

That I cant identify

And Id like to reassure you

But Im not that kind of guy.

Robyn Hitchcock, Raymond Chandler Evening, 1986.

At the conclusion of John Hustons 1941 adaptation of Dashiell Hammetts novel, The Maltese Falcon, private investigator Sam Spade (Humphrey Bogart) turns the woman he has come to love (Mary Astor) over to the police for murdering his partner. She refuses to believe hell betray her, asking, How can you do this to me, Sam? He responds:

Youll never understand me, but Ill try once and give it up When a mans partner is killed, hes supposed to do something about it. It doesnt make any difference what you thought of him. He was your partner and youre supposed to do something about it. And it happens were in the detective business. Well, when one of your organization gets killed, its bad business to let the killer get away with it, bad all around, bad for every detective everywhere Ill have some rotten nights after Ive sent you over, but thatll pass I wont [let you go] because all of me wants to, regardless of consequences.

Spade is giving voice to the ethos of the hardboiled detective, the uncorrupted man who patrols the margins of a fallen world. The genre, which Hammett and Raymond Chandler helped found, would prove to be enduringly popular. They transformed the effete sleuths of Arthur Conan Doyle, Agatha Christie, and Dorothy Sayers drawing rooms into the tough shamuses of the alleyways. The crimes their characters investigated were not unrealistic locked-room murders but the basic, impulsive cruelties that human beings commit out of greed, anger, and corruption. In other words, they embraced realism in all its uncompromising sordidness. As Chandler, whose own signature detective Philip Marlowe would be embodied by Bogart in Howard Hawks The Big Sleep (1946), wrote in his 1950 exegesis of the detective story, The Simple Art of Murder,

The realist in murder writes of a world in which gangsters can rule nations and almost rule cities, in which hotels and apartment houses and celebrated restaurants are owned by men who made their money out of brothels, in which a screen star can be the fingerman for a mob, and the nice man down the hall is a boss of the numbers racket; a world where a judge with a cellar full of bootleg liquor can send a man to jail for having a pint in his pocket, where the mayor of your town may have condoned murder as an instrument of moneymaking, where no man can walk down a dark street in safety because law and order are things we talk about but refrain from practicing; a world where you may witness a hold-up in broad daylight and see who did it, but you will fade quickly back into the crowd rather than tell anyone, because the hold-up men may have friends with long guns, or the police may not like your testimony, and in any case the shyster for the defense will be allowed to abuse and vilify you in open court, before a jury of selected morons, without any but the most perfunctory interference from a political judge.

It is not a very fragrant world, but it is the world you live in, and certain writers with tough minds and a cool spirit of detachment can make very interesting and even amusing patterns out of it. It is not funny that a man should be killed, but it is sometimes funny that he should be killed for so little, and that his death should be the coin of what we call civilization.

The problem is that the definition of realismand sordidnessis always changing as we uncover new layers of perversity. Chandler wrote that the successful detective story did not merely surrender to reality:

In everything that can be called art there is a quality of redemption Down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid. The detective in this kind of story must be such a man. He is the hero, he is everything. He must be a complete man and a common man and yet an unusual man. He must be, to use a rather weathered phrase, a man of honor, by instinct, by inevitability, without thought of it, and certainly without saying it.

Within a quarter of a century of Chandler writing these words, this great cynic would seem nave. It wasnt his concept of the detective that dated, but the idea that the man of honor could defeat evil, or even contain it.

From the time of The Big Sleep, in which Marlowe not only solves the crime (mostly; neither Chandler nor the filmmakers knew who committed one of the murders) but gets the girl to the revision of the genre that came with The Long Goodbye (Robert Altman, 1973), Chinatown (Roman Polanski, 1974), and Night Moves (Arthur Penn, 1975), a great deal had changed. The American Century that had supposedly begun with the successful prosecution of the Second World War and the United States monopoly on the atomic bomb had quickly unraveled. It is difficult to overstate the nations confidence in the immediate postwar period, with the economy surging, the Baby Boom bringing a burst of youth and optimism, and pristine towns and cities when a good chunk of the world had been bombed into rubble. During a September 1945 conference with Secretary of State James F. Byrnes, Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov protested his opposite numbers inflexibility saying the American negotiated as if he had, an atomic bomb in his side pocket. Byrnes replied that that was indeed the case, and, If you dont cut out all this stalling and let us get down to work, Im going to pull an atomic bomb out of my hip pocket and let you have it.

By 1949, the Russians had the bomb, and the difficulties mounted with accelerating speed as the 1950s and 60s passed. By the 1970s, every confidence had been eroded. As the 60s closed, the most shattering items were the ongoing Vietnam War and the Kennedy and King assassinations, but the first years of the new decade offered little respite. In the years immediately preceding and including the release of the aforementioned trio of films, the national mood was tobogganing into the abyss. The war continued, joined by Watergate, the greatest Constitutional crisis since the Civil War. Mixed in were the Kent State massacre; the Attica uprising and resultant slaughter; the trials of Lt. William Calley and Charles Manson; the Boston bussing riots; serial bombings by the Weathermen and other domestic terrorists; the Pentagon Papers, which revealed the governments ongoing deceptions regarding the war; the revelation that the FBI and CIA had engaged in illegal surveillance of American citizens; the first OPEC oil embargo, producing shortages and long lines at gas stations; and runaway inflation and unemployment. Also, the Beatles broke up, Janis Joplin and Jim Morrison died, and disco rose to the top of the charts. This list is by no means inclusive of the misery that kicked off the Have a Nice Day! decade. In 1972, when the radical professor Angela Davis was acquitted of murdering a judge, she was asked if she felt she had received a fair trial. The very fact of an acquittal, she said, meant, there had been no fair trail, because a fair trial would have been no trial at all.

That was the 1970s: It would have been fairer to have skipped the whole thing.

Given the mood, its unsurprising that a certain atmosphere started to manifest itself at the movies. There was a great deal of nostalgia, whether for the 1930s, such as with Paper Moon (Peter Bogdanovich, 1973), The Sting (George Roy Hill, 1973), Dillinger (John Milius, 1973), and Thieves Like Us (Robert Altman, 1974), or the more innocent phase of the 1960s, as with American Graffiti (George Lucas, 1973). Simultaneously, there was the rise of the paranoid thriller with films like Executive Action (David Miller, 1973), The Parallax View (Alan J. Pakula, 1974), The Conversation (Francis Ford Coppola, 1974), and Three Days of the Condor (Sydney Pollack, 1975).

A handful of films tried to straddle the difference, creating the paranoid nostalgic detective film, and it is to this peculiar genre that The Long Goodbye, Chinatown, and Night Moves belong. They subvert Chandlers prerequisite for a successful story. These deeply cynical films say there is no possibility of redemption, the man who is neither mean nor afraid is a fool and honor has no value. The famous last line of Polanskis film (the ending he insisted upon over screenwriter Robert Townes ending, the ending of a Holocaust survivor), spoken to the hero after his journey of 130 minutes has ended in tragedy and disillusionment, is, Forget it, Jake. Its Chinatown. Chinatown here stands in for an open-ended list of other places. Forget it, Jake. Its Los Angeles or Forget it, Jake. Its everywhere.

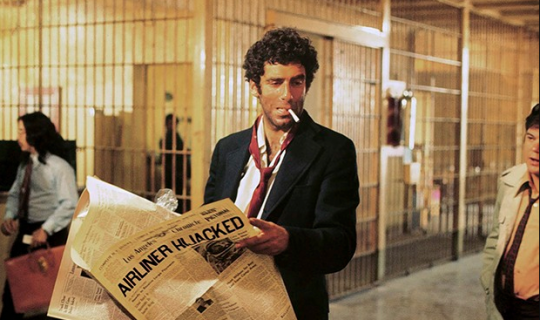

At first, the movie-going public wasnt quite ready to reconsider whether the mean streets might triumph over the man of honor. The Long Goodbye, an adaptation of Chandlers novel of the same name, was initially to be filmed by Peter Bogdanovich, who envisioned Marlowe portrayed by Lee Marvin or Robert Mitchumin other words, a traditional take. Altman preferred his MASH star Elliott Gould. He and scriptwriter Leigh Brackett, who had been one of the writers (along with William Faulkner and Jules Furthman) of Hawks Big Sleep, conceived of Marlowe as an anachronism, a Rip Van Winkle awakening into 70s Los Angeles. The offbeat casting of Gould added to the viewers sense of dislocation. As Gould later told Mitchell Zuckoff for his biography of Altman, I love Robert Mitchum and I love Lee Marvin, and I couldnt argue with them. But youve seen them and you havent seen me.

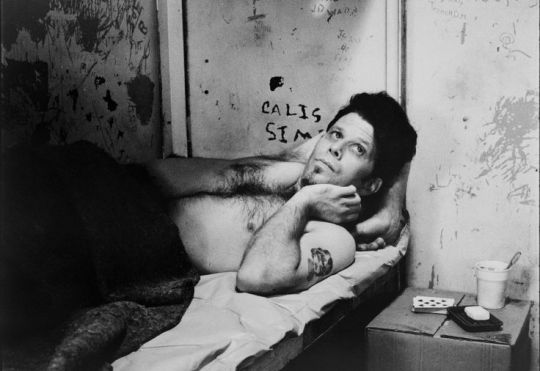

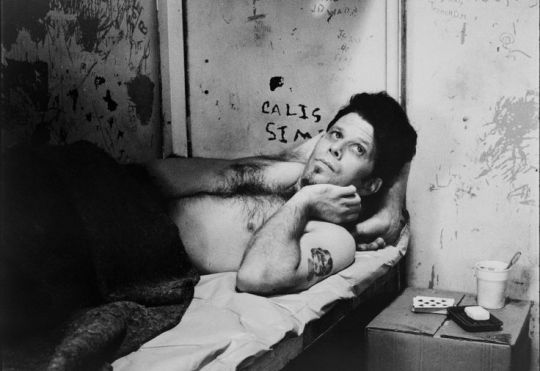

Indeed, Goulds Marlowe had never been seen before, but only because the character had never been placed in such high contrast to his surroundings. This Marlowe is as insouciant as Bogarts, although his quips arent nearly as polished, but unlike Bogarts version thinks hes still the first-person narrator in Chandlers novel; whenever Gould doesnt have another character to talk to, he talks to himself. Sometimes even when he does have another character to talk to he talks to himself. The effect is not unlike that of the original Fleischer Popeye cartoon series, where William Costellos mumbling vocalizations comprise a stream of consciousness that doesnt necessarily match the action on the screen.

In a story only loosely based on Chandlers novel and set in the then-present day, Marlowe is confronted by three concurrent mysteries. His friend Terry Lennox (Jim Bouton, the erstwhile 21-game winner for the 1963 New York Yankees) has supposedly murdered his wife and committed suicide after absconding to Mexico. Marlowe doesnt believe he was the murderer. Simultaneously, he is engaged by Eileen Wade (Nina Van Pallandt) to find her missing husband, the eccentric, alcoholic novelist Roger Wade (Sterling Hayden, going big). Finally, brutal mobster Marty Augustine (Mark Rydell) thinks Marlowe knows the location of the $350,000 of his money Lennox was carrying and demands he return it or face a fatal reprisal.

Looming over all of the above is the problem of Marlowes cat, who has absconded after Marlowe is unable to furnish his or her preferred brand of canned food. As the mysteries unfold, overlap, and cohere (at least to an extent), Marlowe finds that even his ostensible friends cant be trusted, not even the cat, and that rather than being the investigator, the protagonist, of these mysteries, he is merely a puppet on someone elses string.

Neither Gould nor Altman play Marlowe for comedy, but let the films settings and situations emphasize the absurdity of the characters conception; a detective who dealt in the dirty business of the underworld but remained above it would have to be so out of synch with the world around him that his level of detachment would border on the surreal. Finally, the film forces Marlowe to recognize the impossibility of his position and he rejects the limits his creator placed on him. This leads to a jarring final note, especially for devotees of the character, while opening the door to a world in which detective fiction can serve not only as escapism but can cope with the world as we experience it.