Unfriended and the Shifting Definition of a Film Director by Mike DAngelo

By Yasmina Tawil

Picture a film director at work. Once upon a time, the popular image would have been of a man wearing jodhpurs and an oversized hat, sitting in a canvas chair with a megaphone in his hand. Action! Nowadays, the generic look runs to backwards baseball caps and gigantic headphones slung around the neck, and our director (still mostly men, sadly) is more likely to be peering intently at a monitor than shouting instructions. In both cases, though, what springs to mind is the classical shooting process: assemble cast and crew on set or location; decide where to put the camera initially and whether or not to move it from that position during the shot; guide the actors through as many takes as necessary; that’s a wrap.

As anyone who’s ever worked on a movie knows, the above is only a tiny (albeit crucial) aspect of the director’s job, which begins well before principal photography starts and continues long after it ends. “Director” is just a less pompous-sounding synonym for “Orchestrator,” which would really be more accurate. Even a tiny, low-budget film requires hundreds of creative and practical decisions to be made, and while many of those tasks can be delegated, one person (theoretically) is the final arbiter, weighing in on everything from costumes and props to script notes and camera lenses. Consequently, much of what a director does is essentially invisible. At the very least, it’s difficult to ascertain just by watching the film.

The recent horror movie Unfriended makes that more starkly clear than any movie I’ve seen in ages. My gut feeling is that the film is brilliantly directed, by a Georgian-Russian filmmaker named Levan Gabriadze. But it’s hard to say for sure, because few of the usual associations we make with movie directors at work apply in this particular context. Even after watching and reading multiple interviews with Gabriadze (and with the film’s screenwriter, Nelson Greaves), it’s not clear to me how much of Unfriended was shot and how much was more or less created in post-production. Nor am I sure that the distinction matters.

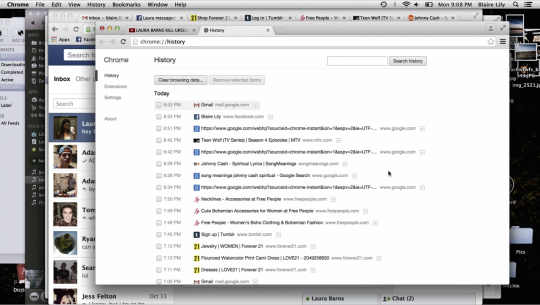

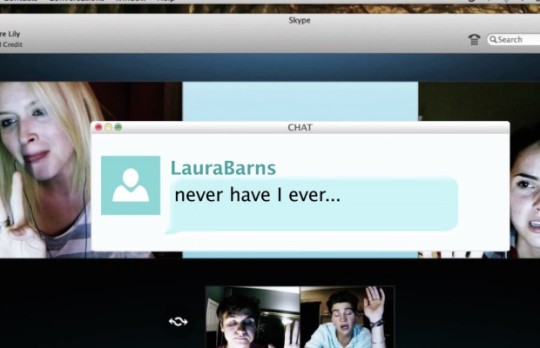

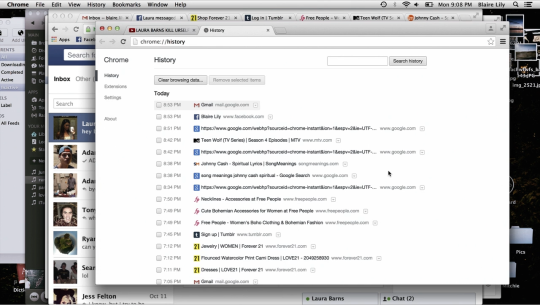

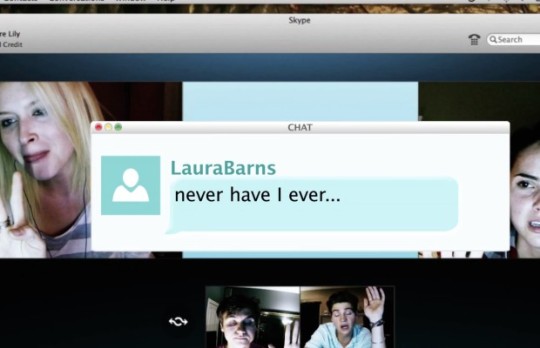

Unfolding in real time, the film takes place entirely (save for the last five seconds) on the screen of a laptop belonging to a young woman named Blaire Lily (Shelley Hennig). Early on, Blaire accepts a Skype call from her boyfriend, Mitch (Moses Jacob Storm), and she eventually winds up simultaneously Skyping with four other friendsas well as the vengeful ghost of a classmate, Laura Barns, who committed suicide after being bullied. The plot is silly, but the technique is astounding. If it were just a bunch of kids yammering at each other in Skype windows (and it becomes that in the second half, unfortunately), it would stilll be pretty impressive, given all the opportunities for things to go wrong. But Unfriended goes much further than that. It’s a movie in which the protagonist, for all intents and purposes, is a cursor.

Right from the beginning, Gabriadze and Greaves (and notice that here, already, I feel compelled to credit both of them, because I’m not at all confident about stating who did what) are remarkably willing to risk alienating viewers. Blaireor, rather, Blaire’s Cursoropens multiple applications throughout that hide her friends from viewthough one face is often partially visible at the edge of the screen, just to keep us alert and paranoid. The Skype windows are consistently obscured, for about 10 minutes straight at one point, in a film that’s barely 80 minutes long. She pulls up Facebook, YouTube, iMessage, Spotify, Gmail, her Chrome history, various websites. And she uses all of those apps exactly the way people use them in real life. When she wants to hear music, we watch as she goes through her playlists (“June playlist,” “lovey shit,” “partayzzzz”), selects one called “rando,” and then clicks on a particular song, which is thankfully not Imagine Dragons’ “Every Night,” clearly visible. But the truth is I’ve never heard that song, so I just now switched over to Safari and pulled up the song’s video on YouTube, and while listening to make sure it’s bad enough for that joke to play, I made a different joke on Twitter (using a dedicated app called Janetter) and quickly checked my email, which for some reason I still do via a UNIX shell, and then I realized that my iMac screen for the last couple of minutes looks exactly like Unfriended. Minus the friends.

(Also Jesus Christ that song is terrible. May I never hear that again.)

Obviously, this would get tedious in a hurry were it not expertly paced, and Gabriadze keeps things moving briskly. Or maybe he just instructed whoever’s handling Blaire’s MacBook to keep things moving brisklyagain, I’m not sure how much of this is post-production wizardry. Plus, most of what Blaire’s Cursor does is at least tangentially related to the narrativeshe’s messaging privately with Mitch about the dead girl, or looking up creepy posts on unexplainedforums.net (not an actual site). But the verisimilitude, especially for Mac users, is off the charts. At one point, Blaire tries to stop whoever’s harassing themusing the dead girl’s Facebook accountby informing Facebook that the account’s owner is deceased, and we watch in real time as she goes through what appear to be all of the actual steps involved in memorializing a Facebook account, including providing a link to an online obituary. By multiplex standards, that’s almost avant-garde (the whole sequence is silent, except for clicking), and it’s topped later by a ticking-clock horror scenario in which Blaire needs to trash a file but temporarily can’t empty her trash because she keeps getting a pop-up alert that says “The operation can’t be completed because the item ‘sample-saturday.night.live.s39e02.miley.cyrus.hdtv.x264-2hd2.mp4’ is in use.”

I’ll say that again: This is a horror movie that wrings suspense from the question of whether a person using a MacBook Pro will figure out, in the nick of time, which application is using a downloaded torrent of a Saturday Night Live episode hosted by Miley Cyrus. And it’s not even the actual episode! It’s a sample!

If you want a sense of what Unfriended looks like, it looks like this: