They Have to Take You In: “Junebug” and the Perils of Homecomings by Daniel Carlson

By Yasmina Tawil

Will Thompson wrote hymns. Born in 1847 in Ohio, he studied at the New England Conservatory of Music and got his start as a composer and lyricist with secular, folksy numbers like “Would I Were Home Again” and “My Home on the Old Ohio.” But it was his work as a writer of religious songs that would bring him the most success. While many of these have faded into history over the past century, one of them is still regularly sung by many churches today, one hundred and thirty-five years after its writing: “Softly and Tenderly,” originally published in 1880. The song is, expectedly, a gentle one, with a few crescendoes built into the chorus, and it’s structured as an exhortation for its listeners to realize that time is short and that salvation has but one path. It’s a song of imploring. It begins:

“Softly and tenderly, Jesus is calling / Calling for you and for me / See, on the portals, he’s waiting and watching / Watching for you and for me.”

Every couplet in the song’s four stanzas ends with “for you and for me,” part of Thompson’s effort to create a feeling of connection among the assembled. From here, he moves into the chorus:

“Come home, come home / Ye who are weary, come home.”

The first line swells and rolls into the second, holding on a long note before backing into a plaintive call of contrition:

“Earnestly, tenderly, Jesus is calling / Calling, o sinner, come home.”

The urgency of the call — for return, for redemption — was clear for Thompson’s intended audience. Thompson was a member of the Churches of Christ, a group of autonomous, loosely organized congregations with no formal dioceses or structure beyond a shared, fervent belief in a very strict interpretation of New Testament texts as the requisite for the reward of a heavenly afterlife. The group sprang from the Restoration Movement of the late 1800s, a name that underscores their sense of feeling incomplete, of looking for some kind of repair in a world beyond. Having come up on paeans to small towns and local communities, Thompson shifted his focus to the spiritual homecomings that would define his work as much as they shaped his beliefs. In other words, when he writes of his vision of being beckoned home, he’s writing about the most peaceful, reassuring thing he can imagine.

///

Home, though, is many things. It’s as often a prison as it is a refuge, and the struggle between those meanings is what shapes 2005’s Junebug. Written by playwright Angus MacLachlan and directed by Phil Morrison, the film is a small, delicate examination of wounds that won’t heal and relationships that won’t settle, and its story is catalyzed by and centered on a homecoming.

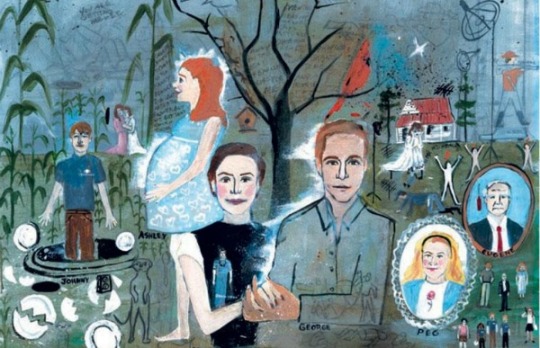

Madeleine (Embeth Davidtz), an art dealer based in Chicago, meets George (Alessandro Nivola) at an auction one night at her gallery. She’s taken with him almost instantly, and they elope after only a week. A few months later, she gets a chance to sign a contract with an artist near George’s hometown of Pfafftown, North Carolina, so they drive down to spend a few days with George’s family. Morrison manages to breeze through all this set-up without making anything feel rushed, and it’s because the cold, generic city environment isn’t where this story is going to happen. The film is bound for Southern forests, and soon enough, George and Madeleine are walking into the wood-paneled home of George’s family: mother Peg (Celia Weston), father Eugene (Scott Wilson), brother Johnny (Ben McKenzie), and Johnny’s pregnant wife, Ashley (Amy Adams). The dynamic here is evident even without the dialogue. Peg is kind but overbearing and mistrustful of major change; Eugene is quietly toodling along in his own little world; Johnny is so angry and depressed at having to live in his parents’ home that he’s never more than one bad remark away from snapping; and Ashley is eager, generous, loving, and ensconced in denial about her husband and her future. Johnny resents George for a host of reasons that are never named, but they don’t need to be: George lives in Chicago and is doing well enough to buy expensive art, while Johnny works at a factory and half-heartedly studies for his GED in his spare time. Peg’s silences feel freighted with judgment and curiosity, while Eugene’s feel like those of someone who’s been running on autopilot for years. And through it all trundles Ashley, due to deliver any day, her pregnancy a blunt metaphor for the looming atmosphere of change and family restructuring.

George’s trip home, though, is really about Madeleine. She’s the newcomer, the foreigner, and MacLachlan and Morrison highlight her outsider status by keeping her and George apart for much of their trip. Not long after they arrive, Madeleine’s cornered at the breakfast table and interrogated by an excited Ashley, while George ambles by outside, lost in his own thoughts, seen in a quick shot before he disappears past the edge of the house. George will crack a beer with his father or take a nap while Madeleine finds herself making awkward small talk with Peg or being recruited into helping Johnny write a paper. George leaves Madeleine to fend for herself, a passive act that begins to put some space between them; that space is amplified by Madeleine’s rocky encounters and general inability to fit it, as well as her dawning understanding of how little she really knows about the man she married only six months earlier. For George, the trip is a homecoming, but for Madeleine, it’s an expedition into strange territory, and the more George fits in, the more she stands out. What is marriage if not a journey into the unknown land of another person? Their history, their life, the stories that shaped them?

Junebug is beautifully spare and precise in its observations about the way relationships are built and defined, and it slowly works toward a scene of quiet, moving recognition of what we hide from each other. One night, when the family’s attending a potluck dinner at the local church, George is called upon by the pastor to perform a hymn for the congregation. Smiling sheepishly but playing along, he picks up a hymnal and, with the help of two other singers, begins to sing a song of homecoming and longing, the only song that could possibly fit the moment: “Softly and Tenderly.”

It’s a strong performance — Nivola has a nice voice, as do the men singing backup — but the power of the scene is all in the reaction of the family. They sit stock-still as he sings, rapt. Peg mouths some of the lyrics, Eugene nods slightly, Ashley gapes with pure love; even Johnny, who starts out with his back to George, turns around at one point to witness it. But Madeleine’s face shows a blend of confusion, fascination, and growing awareness of where George came from and who he really is. She’s looking back in time, seeing who he really is. How often is that possible? To what lengths do we go to avoid just such circumstances? She’s engaged and entertained by George’s performance, and when it’s over, she sees him with new eyes. There’s no judgment involved, or horror, or paranoia that maybe this man isn’t who she thought he was; rather, she’s learning who this man is by seeing where he came from.

The song isn’t just a connection to his past, but a reflection of his family’s yearning for his return: come home, come home. They’re the ones who’ve been calling him back. George has been the adventurous son, now welcomed home like the prodigal, and Johnny struggles in silence while the family attempts to recreate what’s long gone. George is indeed weary — he sleeps heavy and frequently while he and Madeleine are in Pfafftown — and all too eager to withdraw into some kind of childish simulation of real life.

The moment of revelation in his performance is, in its way, Madeleine’s real initiation into the family, and as such, her presence or absence from the events that follow have more effect than they would have previously. Ashley goes into labor on the same afternoon Madeleine has to make a last-ditch effort to sign her elusive artist, David Wark (Frank Hoyt Taylor), and while narratively this is as clean a character choice as you could want (help her husband’s family or pursue her own glory), there’s more to it than that. Rather, this is George’s chance to engage with the family he’s mostly ignored for the entire trip. With Madeleine out in the woods chasing down the painter, it falls to George to hold the family together when the worst happens: Ashley’s baby dies at birth. George is called upon to do the one thing he’s avoided doing this whole time, and the exact thing forced upon Madeleine — to open up and accept his connection to the family.

So much of the film’s resonance comes from its setting. There’s a distinct Southern-ness shot through the film that gives it its shape. Wark’s art — created for the film by Ann Wood — is populated by surreal, sexually graphic reinterpretations of Civil War imagery, underscoring the sense that Madeleine isn’t just visiting her in-laws, but somehow traveling to a different world and time. The creative team brings their own experience to bear here, too. Morrison and MacLachlan both have ties to North Carolina: Morrison was born in Winston-Salem, while MacLachlan graduated from North Carolina School of the Arts Drama School and lived in Winston-Salem at the time the film was made. Scott Wilson, Celia Weston, and Ben McKenzie all spent time in the South. As a result, the film possesses a lived-in quietude that feels completely real, providing an almost documentary-like reality to the backdrop of the film’s central relationship. Madeleine is doomed to never fit in, and George has to come to the conclusion that he doesn’t anymore. There’s a balance to their self-discoveries, as well as to what they learn about each other in the process: she sees him as he used to be, and he finally sees her as apart from himself. George’s real lament is that, for all his desire, he can’t come home. Not like he wants to, anyway, and not like the hymn would let him believe.

///

Morrison never lets up on this sense of alienation within one’s own family and home, reinforcing George and Madeleine’s struggle in subtle ways: in addition to being separated for the film’s climaxes, they don’t share the frame right away when they’re reunited. It’s not really until they’re back on the road, northbound for the new home they’ve made for themselves, that they start to feel like a unit again, her hand idly playing with the hair at the nape of his neck while he drives. As they make their leisurely highway escape, a new awareness sits between them, unseen and unacknowledged. It’s the awareness both of how they’ve grown closer and of the price they paid to do so, the same price everyone pays. Homecomings are never as idyllic as we want them to be. The hymn was, after all, about a vision of the afterlife. Such comforts are often harder to find in the day to day. Appropriately, it was another Southerner and North Carolinian, Thomas Wolfe, who mourned, “You can’t go back home to your family, back home to your childhood … back home to places in the country, back home to the old forms and systems of things which once seemed everlasting but which are changing all the time — back home to the escapes of Time and Memory.” That knowledge was hard-won. Is there any other way to learn?