They Have to Take You In: Junebug and the Perils of Homecomings by Daniel Carlson

By Yasmina Tawil

Will Thompson wrote hymns. Born in 1847 in Ohio, he studied at the New England Conservatory of Music and got his start as a composer and lyricist with secular, folksy numbers like Would I Were Home Again and My Home on the Old Ohio. But it was his work as a writer of religious songs that would bring him the most success. While many of these have faded into history over the past century, one of them is still regularly sung by many churches today, one hundred and thirty-five years after its writing: Softly and Tenderly, originally published in 1880. The song is, expectedly, a gentle one, with a few crescendoes built into the chorus, and its structured as an exhortation for its listeners to realize that time is short and that salvation has but one path. Its a song of imploring. It begins:

Softly and tenderly, Jesus is calling / Calling for you and for me / See, on the portals, hes waiting and watching / Watching for you and for me.

Every couplet in the songs four stanzas ends with for you and for me, part of Thompsons effort to create a feeling of connection among the assembled. From here, he moves into the chorus:

Come home, come home / Ye who are weary, come home.

The first line swells and rolls into the second, holding on a long note before backing into a plaintive call of contrition:

Earnestly, tenderly, Jesus is calling / Calling, o sinner, come home.

The urgency of the call for return, for redemption was clear for Thompsons intended audience. Thompson was a member of the Churches of Christ, a group of autonomous, loosely organized congregations with no formal dioceses or structure beyond a shared, fervent belief in a very strict interpretation of New Testament texts as the requisite for the reward of a heavenly afterlife. The group sprang from the Restoration Movement of the late 1800s, a name that underscores their sense of feeling incomplete, of looking for some kind of repair in a world beyond. Having come up on paeans to small towns and local communities, Thompson shifted his focus to the spiritual homecomings that would define his work as much as they shaped his beliefs. In other words, when he writes of his vision of being beckoned home, hes writing about the most peaceful, reassuring thing he can imagine.

///

Home, though, is many things. Its as often a prison as it is a refuge, and the struggle between those meanings is what shapes 2005s Junebug. Written by playwright Angus MacLachlan and directed by Phil Morrison, the film is a small, delicate examination of wounds that wont heal and relationships that wont settle, and its story is catalyzed by and centered on a homecoming.

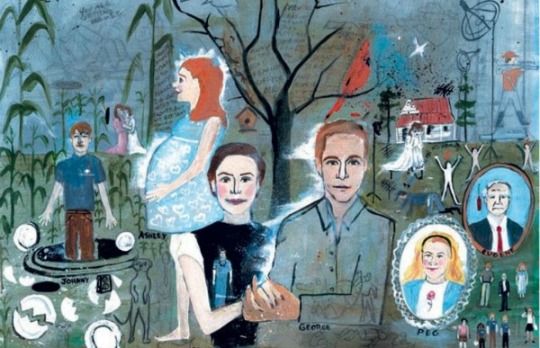

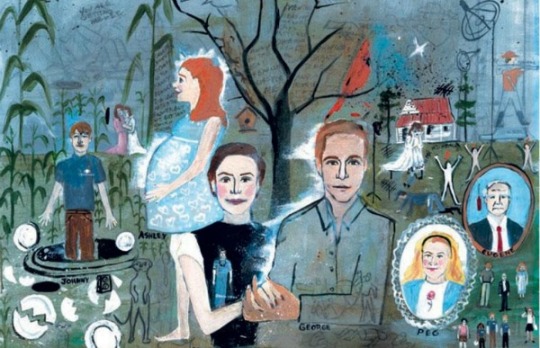

Madeleine (Embeth Davidtz), an art dealer based in Chicago, meets George (Alessandro Nivola) at an auction one night at her gallery. Shes taken with him almost instantly, and they elope after only a week. A few months later, she gets a chance to sign a contract with an artist near Georges hometown of Pfafftown, North Carolina, so they drive down to spend a few days with Georges family. Morrison manages to breeze through all this set-up without making anything feel rushed, and its because the cold, generic city environment isnt where this story is going to happen. The film is bound for Southern forests, and soon enough, George and Madeleine are walking into the wood-paneled home of Georges family: mother Peg (Celia Weston), father Eugene (Scott Wilson), brother Johnny (Ben McKenzie), and Johnnys pregnant wife, Ashley (Amy Adams). The dynamic here is evident even without the dialogue. Peg is kind but overbearing and mistrustful of major change; Eugene is quietly toodling along in his own little world; Johnny is so angry and depressed at having to live in his parents home that hes never more than one bad remark away from snapping; and Ashley is eager, generous, loving, and ensconced in denial about her husband and her future. Johnny resents George for a host of reasons that are never named, but they dont need to be: George lives in Chicago and is doing well enough to buy expensive art, while Johnny works at a factory and half-heartedly studies for his GED in his spare time. Pegs silences feel freighted with judgment and curiosity, while Eugenes feel like those of someone whos been running on autopilot for years. And through it all trundles Ashley, due to deliver any day, her pregnancy a blunt metaphor for the looming atmosphere of change and family restructuring.

Georges trip home, though, is really about Madeleine. Shes the newcomer, the foreigner, and MacLachlan and Morrison highlight her outsider status by keeping her and George apart for much of their trip. Not long after they arrive, Madeleines cornered at the breakfast table and interrogated by an excited Ashley, while George ambles by outside, lost in his own thoughts, seen in a quick shot before he disappears past the edge of the house. George will crack a beer with his father or take a nap while Madeleine finds herself making awkward small talk with Peg or being recruited into helping Johnny write a paper. George leaves Madeleine to fend for herself, a passive act that begins to put some space between them; that space is amplified by Madeleines rocky encounters and general inability to fit it, as well as her dawning understanding of how little she really knows about the man she married only six months earlier. For George, the trip is a homecoming, but for Madeleine, its an expedition into strange territory, and the more George fits in, the more she stands out. What is marriage if not a journey into the unknown land of another person? Their history, their life, the stories that shaped them?

Junebug is beautifully spare and precise in its observations about the way relationships are built and defined, and it slowly works toward a scene of quiet, moving recognition of what we hide from each other. One night, when the familys attending a potluck dinner at the local church, George is called upon by the pastor to perform a hymn for the congregation. Smiling sheepishly but playing along, he picks up a hymnal and, with the help of two other singers, begins to sing a song of homecoming and longing, the only song that could possibly fit the moment: Softly and Tenderly.