May We Always Go on Singing: “Sunshine” and Making Peace With the Past by Daniel Carlson

By Yasmina Tawil

“There is a scene where they are leaving the building where they have just changed their name, and they are laughing and happy. My heart was sad shooting those shots, my heart was sad editing the scene, and my heart is sad every time I see it, because I know this was the first and the greatest mistake they made. I want to yell at them, ‘Why are so happy. Are you crazy?’”

— István Szabó

“If there’s no God, and there never was a God, then why do we miss him so much?”

— Ivan Sors

///

István Szabó is haunted. Born in Hungary in 1938, he began his career as a writer-director right after high school, attending an academy for theater and film, where he cut his teeth on shorts before graduating to features. Before he was 30 years old, he was making films about the intersection of his personal history and the tumult his nation had seen in the twentieth century. He was drawn to the occupation of Hungary by the Nazis during the second world war, the passing of the torch to the Communists, the people’s uprising of 1956; all things that had shaken his homeland and reshaped his own family. These things sound so long ago now, but that’s something else that Szabó would explore in his work — the way history isn’t really history, and how we’re never free from our past or our past selves. Over and over again, Szabó would return to the wars that had sent cracks through Europe in the first half of what was supposed to be a century of tolerance and progress, finding new ways to explore what it was like to come of age in such a time. He also became increasingly focused on what we’d today call identity politics: the meaning of one’s name, faith, heritage, and fortune, and the degrees to which we’re willing to compromise those things when we tell ourselves such compromises are necessary for our success. In other words, Szabó was worried about the high personal cost of surviving in a world that always seemed ready to strike you down, and in 1999, he made a masterpiece about what it takes to keep going: Sunshine.

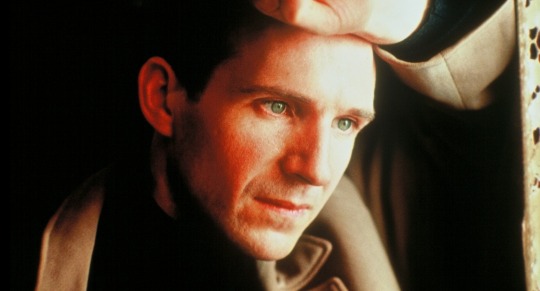

Sunshine is the kind of historical drama to which one can apply descriptors like “sweeping” and “grandiose” without sounding hyperbolic. It deals with the members of the Sonnenschein bloodline, a family of Hungarian Jews, from the late-nineteenth through the mid-twentieth century, and while it technically touches on five generations, three of them form the core of the film. In a move that could have been a gimmick in less capable hands and might have proved disastrous with a less worthy performer, Ralph Fiennes gracefully plays three successive generations of Sonnenschein men: Ignatz, born in the late 1800s and eventually involved in the politics and military operations of World War I; Adam, who reaches adulthood in the 1930s as the Nazis are coming to power; and Ivan, who survives a labor camp and grows up to work for the Communist regime. Szabó, who co-wrote with playwright Israel Horowitz, is fascinated the evolution of identity and the tension between assimilation and independence. The name “Sonnenschein” means “sunshine,” and it’s easy to see the association with light, clarity, honesty. It’s by light that we see. The film, though, is a look at what happens when identity gradually erodes and the light begins to dim, and it starts with the names. Ignatz, a promising lawyer, is told that he needs a “more Hungarian” — read: less Jewish — name if he’s going to become a judge, so he decides to change his surname to Sors. His siblings go along with the name change, too: Ignatz’s brother, Gustave (James Frain), and their cousin, Valerie (Jennifer Ehle), who grew up in their home after her father died and was raised as their sister. When they change their name, they’re almost giddy with the possibilities before them, and they practically prance out of the government building where they completed the paperwork. But Szabó doesn’t rejoice with them, and the gentle camera and absence of music lend the moment a kind of sadness. This is the first step in giving away who you are: to forfeit your name in an attempt to fit in. The sunshine has been hidden, and darkness is allowed to seep in. The siblings picked “Sors” for its sound, but also, ironically, for its meaning: “fate.”

Each of the three men will, over the course of their lives, move through similar moments of doubt and crisis. It’s not fair to call them placeholders — Szabó gives them more personality than that, and Fiennes does a beautiful job giving each one his own presence — but they do serve a broader symbolic purpose. They wind up representing successive moves away from identity and integrity and toward assimilation and self-negation. Ignatz begins the process by abandoning the family name so he can more faithfully serve his empire, turning a deaf ear to Gustave’s calls for revolution. Adam, who pursues the life of a sportsman and aspires to be the best fencer in the country, converts to Roman Catholicism so he can join the army officers’ fencing club. And Ivan, out of anger and shame, becomes a police officer for the Communist state to persecute those who were complicit in Germany’s crimes. Name, faith, nation: each man sheds a layer of the skin that was passed down to him, until the Sors family is an unrecognizable fraction of what it used to be. They each try to do what seems, at the time, like the right thing, only to realize after the fact what they’ve traded away. Szabó underscores this circularity through visual motifs. Early sections of the film are warmly lit and take place under sunny skies, but by the end, we’ve moved to the blunt, industrial architecture of mid-century, and Szabó’s characters find themselves lost amid gray rubble. There’s also a beautiful use of eerie green light to symbolize contamination and corruption. It first appears emanating from a radio dial as Adam and his family listen to an announcement about the passage of laws designed to curtail Jewish activity in Hungary, and it reemerges in the state offices that Ivan will occupy. What was once just a force reaching out from afar has now become something surrounding our family, almost without our knowledge. Green, too, is the color of envy, and what is Ivan’s thirst for power if not an unnamed envy of those who never have to worry about their ethnicity?

Each man is also doomed to romantic tragedy that externalizes his identity crisis, and each relationship is also progressively rougher and less tender. Ignatz falls in love with Valerie, his first cousin. Their affair is the most passionate and vulnerable of the three in the film, which also means it causes the most devastation. Ignatz and Valerie’s time together is idyllic to start: happy nights and days together, heartfelt declarations of devotion, a picnic that leads to lovemaking. They’re discovered, though, and Ignatz is chastened by his father until he decides to move away and pursue his career. Although they eventually reunite and marry, it’s never quite enough, and Ignatz’s full-hearted quest for political glory — he rises through the judiciary and is invited to stand for office — puts him at odds with a wife who sympathizes with the plight of the poor. Years later, Adam is ascending the ranks of his sport when he’s pursued by Greta (Rachel Weisz), his brother’s wife. They only ever meet in a darkened apartment, and their relationship is based on mutual delusion: Greta thinks Adam will leave his own wife and run off with her, while Adam is hiding from his own feelings about hiding his identity from his teammates. In the final section of the film, Ivan strikes up a relationship with a married fellow officer, Carole (Deborah Kara Unger). Their sex is furtive, frantic: against a tree off the beaten path, or in Ivan’s office late at night. Szabó allows each man less freedom and happiness, less room to experience connection, as the weight of their generational flight from themselves bears down. Each man also wants what he cannot socially have: Ignatz, his cousin, raised as his sister; Adam, his married sister-in-law; Ivan, the wife of a superior. Their desires are thwarted and their relationships torn apart. It’s not coincidence, though. Through Szabó’s eyes, the Sonnenschein/Sors men are paying a price for their infidelity to identity. Ignatz could be happy with Valerie, Adam with his wife, Ivan with anyone else. But by breaking a covenant with their forebears, they invite a curse upon themselves. Their actions bear the fruit of the worry expressed by Ignatz’s father, Emmanuel Sonnenschein (David de Keyser), who built his fortune selling tonic and who, whenever joy approached, asked himself, “What will come of this? What terrible price will I have to pay?” Even the name Emmanuel means “God with us.” The further Emmanuel’s descendants get from him, the weaker their faith and the less certain they are about their identity.

Aesthetically, the film becomes a statement about the self-loathing that comes with assimilation. Ignatz finds himself surrounded by people who want him to change his name; it feels like only a blink of the eye, and Adam is fencing at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, surrounded by a crowd of Nazis. Adam and his son, Ivan, are transported to a labor camp as Hungary’s occupation by the Nazi forces, and Ivan becomes a part of the state machine when he reaches adulthood because he feels guilty for not trying to do more to help his father survive the camp. The camp is the key to the first part of what’s driving Szabó. It’s only in one scene here, but it’s the most horrific in the film. Adam’s character was inspired by the real-life Hungarian fencer Attila Petschauer, who had received a temporary exemption from occupied Hungary’s anti-Jewish laws out of deference to his Olympic prowess, but who was nonetheless eventually deported to a concentration camp, where he was killed. Adam meets the same fate, and is indeed murdered with the same method used on Petschauer: he is stripped, beaten, strung up in a tree, and sprayed with water until he freezes to death.

That Ivan does nothing to help his father becomes his motivating shame. He survives to see the camp liberated and becomes a willing tool of the new Communist state to punish those who stood idly by as he himself did. His fervor leads him to betray his friends in the state and engage in a relationship that could destroy him, and Szabó seems to come down hardest on Ivan. Each of the three men forfeits some part of himself to get ahead, but Ivan’s is the most drastic, the most ruthless of reshapings. And this is the second part of what’s going on here. Szabó’s films are often heavily autobiographical, returning to the same ground to play out the horrors of history over and over again, but Ivan isn’t just some projection of Szabó’s own beliefs about the dangers of complicity with power. He’s a manifestation of Szabó’s own self: Shortly after the 1956 revolution, Szabó worked as a secret informant for the Internal Reactionary Prevention unit of the Communist party, reporting on many of his colleagues and instructors at the film academy. Ivan is, then, a re-creation of Szabó in the artist’s own hand, and an attempt to atone for what he’d done.

None of that knowledge was public at the time of the film’s release, of course. The story didn’t come out until 2006, when the Hungarian paper Élet és Irodolam (Life and Literature) reported on the activity. The revelation has a way of retroactively adding new layers to Sunshine, which was already a masterful work of historical fiction but now also serves as one man’s fictive penance. It’s no wonder Szabó makes things so tough for Ivan. That was himself up there on the screen.

Szabó’s cinematic apologia is made up of repetition almost as a way to lay out his own history and try to make sense of it. One of the family’s dishes shatters each generation in a moment of argument or anger; parents and children worry about their power to curse each other. Landscapes and buildings reappear with new faces and purposes. Ignatz’s mother blesses the family on special occasions with a simple prayer, “Please God, may we always go on singing,” that the children take and repeat as ages pass. One of the most moving doublings feels almost supernatural: a young Valerie plucks a thorn from her foot only to have the moment photographed by Gustave with her own camera; years later, at a museum, Adam briefly inspects a Boy With Thorn sculpture that’s in the same position as Valerie in the photo. Szabó lays these things in to call to mind time’s ceaseless flow, moving like an unforgiving river as it sweeps up and entangles everything in its path. Szabó also evokes historical dramas of the past with a lush score from Maurice Jarre, the composer behind the David Lean epics Lawrence of Arabia and Doctor Zhivago, among others. The music gives the film itself, as a work of art, a link to the past that mirrors its story’s devotion to honoring one’s roots. Similarly, in a brilliant bit of casting, Valerie is played as a young woman by Jennifer Ehle and as an older woman by Rosemary Harris, Ehle’s actual mother. It makes the film feel profoundly grounded, as if we’ve actually watched Valerie grow old, and together with Fiennes’ outstanding work, it presents a realistic portrait of one family struggling through the ages.

Yet Szabó is also, crucially, not a nihilist. As he must have hoped for redemption for his mistakes and freedom from his guilt, so, too, do the characters in Sunshine find ways to make good on what they’ve done. If the men in the film are agents of destruction, the women in their life are catalysts for reconciliation, especially Valerie. Valerie loves Ignatz even after she realizes their relationship has to end, and she never stops pushing him to understand the worth of the least of those around him. She is the constant beating heart of the film, and she shepherds the family down through the generations. Each of the three men loses something when he gives up part of his identity, but he’s redeemed when he finds a way to reclaim it. Ignatz in his old age is asked to oversee trials against Communist agitators, but he declines, citing a preference for justice over retribution. Adam is beaten by concentration camp guards when he refuses to deny his Olympic status. And Ivan, in the end, finds himself spit out of the machine and unsure of anything other than this: that his family has always been a part of who he’s been. It’s Ivan who finally changes his name back to Sonnenschein, choosing to be himself instead of live in the shadow of borrowed destiny, and when he does a weight lifts from him. Szabó shoots him strolling down the street with pride, a genuine smile on his lips, and something on his shoulders we’d almost forgotten about: the light of the morning sun.