From Massacre to Massacre: The Heyday of Tobe Hooper, Horrors Misunderstood Provocateurby Noel Murray

By Yasmina Tawil

Poltergeist is by no means the greatest horror movie ever made, but its first 45 minutes offers one of the best sustained stretches of scares, jokes, and subtle subversion in the history of the genre. Long before the suburban Freeling family initiates Poltergeists plot by asking paranormal investigators about the disappearance of their daughter Carol Anne, the film spends over a third of its running-time jumping from everyday annoyances to supernatural disturbances, depicting modern life as damned at its root. Television remotes malfunction. A pet bird dies. A 12-pack of beer explodes. Construction workers leer at a teenage girl. Chairs spontaneously move. A gnarled tree smashes through the Freelings upscale Orange County home. The why of all of this is put off for as long as possible, as the movie takes its time to generate an environment of queasy unease, punctuated by puckish social satire and moments of outright fear.

Heres the question, though: Who deserves the credit for Poltergeists brilliant opening act? Director Tobe Hooper? Or co-writer/producer Steven Spielberg?

Poltergeist was the best and worst thing to happen to Hooper. The movie marked his graduationhowever brieflyfrom low-budget drive-in fare to Hollywood blockbusters. It was such a success that he soon signed a contract with Cannon Films for three more mid-budget pictures. But the first two projects released under the deal didnt resemble either Poltergeist or Hoopers 1974 cult sensation The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, which left critics, producers, and audiences confused as to what kind of filmmaker he intended to be. Meanwhile, rumors persisted that Spielberg had directed most of Poltergeist himself, because Hooper was too indecisive on the set. Then in 1986, Hooper made the commercially disappointing The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2, and that was pretty much it for him as any kind of artistic force in shock-cinema.

It shouldnt have gone this way. In the 1970s, Spielberg and his New Hollywood compadresMartin Scorsese, Brian De Palma, George Lucas, and their mutual mentor Francis Ford Coppolastitched together what theyd learned from classic American studio films, European art-house fare, and disreputable B-pictures, and then threaded the resultant patchwork with their personal concerns and stylistic flourishes. They brought artistic credibility to pop and pulp, and were richly rewarded for it.

Meanwhile, in their own tributary of the mainstream, directors like Hooper, George Romero, and John Carpenter were shadowing Spielbergs gang, with less fanfare. Each of these three filmmakers made massive hitChain Saw, Night Of The Living Dead, and Halloweenand in the decade that followed, each more or less stayed true to their origins in tawdry exploitation. While making shoestring monster movies and offbeat adventures, they brought just as much of a personal stamp as Scorsese, with their own unique combinations of high- and low-art influences.

Carpenter and Romero have largely gotten their due from critics and scholars, however belatedly. Hoopers legacy has been less secure. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is in the cinematic pantheon, but beyond that, only Poltergeist gets much attention from non-connoisseurs and thats primarily because of the Spielberg connection. Yet for 12 years, from Chain Saw to Chainsaw 2, Hooper directed eight movies that collectively are as daring and visionary as Romero and Carpenters output in the same era. These films are often heavily flawed, but charged with a fervid intensity, and guided by a purposeful mind.

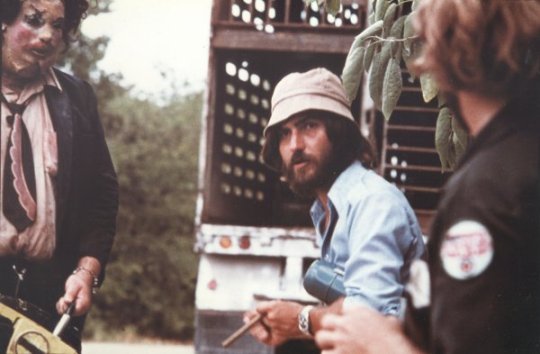

Hooper grew up in Austin, Texas, and attended UT in the early 1960s, becoming one of the first students in the colleges fledgling film program. He drifted into a career as a cameraman-for-hire, working mainly for the local public television station. By the end of the decade, hed begun shooting an experimental head movie called Eggshells, which is more a demo reel of his technical know-how than it is a proper film. During the production, Hooper befriended writer Kim Henkel, who shared his passion for cinema, his ambition to work in Hollywood, and his certainty that their ticket to the big time wouldnt be another Eggshells.

Seeing Night Of The Living Deador, more importantly, seeing how much money a micro-budget movie from Pittsburgh could rake inHooper and Henkel realized they could get noticed with a horror film without having to leave Austin. Inspired by the pervasive violence of early 1970s culture and the primal terror of Hansel & Gretel, the pair whipped up The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, a gonzo slasher with darkly comic elements and a disturbing docu-realistic grime. Shot over the course of one sweltering Round Rock summer in 1973, the movie was a miserable experience for the cast, whose treatment at the hands of the crew and their fellow actors bordered on the actionably abusive. The shoot wasnt much happier for Hooper, Henkel, and their talented cinematographer Daniel Pearl, who were under-prepared, and dealing with financial backers who didnt understand why they were adding sick humor and fancy camera moves to a movie that would sell based on its title alone.