From Massacre to Massacre: The Heyday of Tobe Hooper, Horror’s Misunderstood Provocateur by Noel Murray

By Yasmina Tawil

Poltergeist is by no means the greatest horror movie ever made, but its first 45 minutes offers one of the best sustained stretches of scares, jokes, and subtle subversion in the history of the genre. Long before the suburban Freeling family initiates Poltergeist’s plot by asking paranormal investigators about the disappearance of their daughter Carol Anne, the film spends over a third of its running-time jumping from everyday annoyances to supernatural disturbances, depicting modern life as damned at its root. Television remotes malfunction. A pet bird dies. A 12-pack of beer explodes. Construction workers leer at a teenage girl. Chairs spontaneously move. A gnarled tree smashes through the Freeling’s upscale Orange County home. The “why” of all of this is put off for as long as possible, as the movie takes its time to generate an environment of queasy unease, punctuated by puckish social satire and moments of outright fear.

Here’s the question, though: Who deserves the credit for Poltergeist’s brilliant opening act? Director Tobe Hooper? Or co-writer/producer Steven Spielberg?

Poltergeist was the best and worst thing to happen to Hooper. The movie marked his graduation—however briefly—from low-budget drive-in fare to Hollywood blockbusters. It was such a success that he soon signed a contract with Cannon Films for three more mid-budget pictures. But the first two projects released under the deal didn’t resemble either Poltergeist or Hooper’s 1974 cult sensation The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, which left critics, producers, and audiences confused as to what kind of filmmaker he intended to be. Meanwhile, rumors persisted that Spielberg had directed most of Poltergeist himself, because Hooper was too indecisive on the set. Then in 1986, Hooper made the commercially disappointing The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2, and that was pretty much it for him as any kind of artistic force in shock-cinema.

It shouldn’t have gone this way. In the 1970s, Spielberg and his “New Hollywood” compadres—Martin Scorsese, Brian De Palma, George Lucas, and their mutual mentor Francis Ford Coppola—stitched together what they’d learned from classic American studio films, European art-house fare, and disreputable B-pictures, and then threaded the resultant patchwork with their personal concerns and stylistic flourishes. They brought artistic credibility to pop and pulp, and were richly rewarded for it.

Meanwhile, in their own tributary of the mainstream, directors like Hooper, George Romero, and John Carpenter were shadowing Spielberg’s gang, with less fanfare. Each of these three filmmakers made massive hit—Chain Saw, Night Of The Living Dead, and Halloween—and in the decade that followed, each more or less stayed true to their origins in tawdry exploitation. While making shoestring monster movies and offbeat adventures, they brought just as much of a personal stamp as Scorsese, with their own unique combinations of high- and low-art influences.

Carpenter and Romero have largely gotten their due from critics and scholars, however belatedly. Hooper’s legacy has been less secure. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is in the cinematic pantheon, but beyond that, only Poltergeist gets much attention from non-connoisseurs… and that’s primarily because of the Spielberg connection. Yet for 12 years, from Chain Saw to Chainsaw 2, Hooper directed eight movies that collectively are as daring and visionary as Romero and Carpenter’s output in the same era. These films are often heavily flawed, but charged with a fervid intensity, and guided by a purposeful mind.

Hooper grew up in Austin, Texas, and attended UT in the early 1960s, becoming one of the first students in the college’s fledgling film program. He drifted into a career as a cameraman-for-hire, working mainly for the local public television station. By the end of the decade, he’d begun shooting an experimental “head movie” called Eggshells, which is more a demo reel of his technical know-how than it is a proper film. During the production, Hooper befriended writer Kim Henkel, who shared his passion for cinema, his ambition to work in Hollywood, and his certainty that their ticket to the big time wouldn’t be another Eggshells.

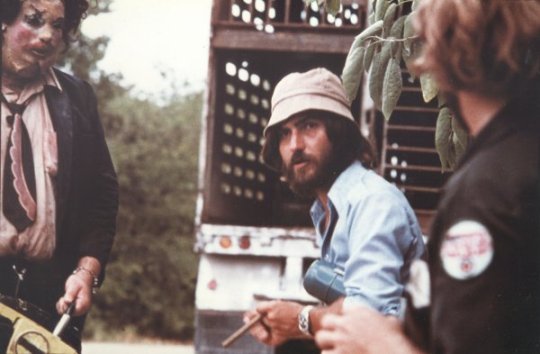

Seeing Night Of The Living Dead—or, more importantly, seeing how much money a micro-budget movie from Pittsburgh could rake in—Hooper and Henkel realized they could get noticed with a horror film without having to leave Austin. Inspired by the pervasive violence of early 1970s culture and the primal terror of Hansel & Gretel, the pair whipped up The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, a gonzo slasher with darkly comic elements and a disturbing docu-realistic grime. Shot over the course of one sweltering Round Rock summer in 1973, the movie was a miserable experience for the cast, whose treatment at the hands of the crew and their fellow actors bordered on the actionably abusive. The shoot wasn’t much happier for Hooper, Henkel, and their talented cinematographer Daniel Pearl, who were under-prepared, and dealing with financial backers who didn’t understand why they were adding sick humor and fancy camera moves to a movie that would sell based on its title alone.

The money-men were right about Chain Saw’s salability. Controversial even before it was released—with the name alone representing a new low in sleaze, according to the media establishment—The Texas Chain Saw Massacre was cleverly marketed, with an equal focus on its gamy verisimilitude and its artistic merit. (“After you stop screaming, you’ll start talking about it,” the trailer boasted.) But the film really did live up to its hype. Hooper may have seemed distant and confused on the set, but in telling the story of a group of obnoxious road-tripping youngsters—who knock on the wrong door out in the country and end up getting dismembered by inbred redneck cannibals—he demonstrated a rare command of craft, which he often weaponized to torment audiences. The macabre, bone-strewn decor (courtesy of art director Robert Burns) and the jarring no-set-up kills (made all the more upsetting by the performance of the hulking Gunnar Hansen as the masked “Leatherface”) delivered the scares the premise promised. And the beautiful low-angle tracking shots and overpowering sense of decay revealed an artistry underneath the mayhem.

Almost as soon as Chain Saw became a hit, Hooper and Henkel hightailed it to California, and started shopping around a script for a murder-mystery. The project didn’t find any buyers, but the duo did land a three-picture deal at Universal, and an offer to jump aboard indie impresario Mardi Rustam’s long-gestating Jaws-meets-Psycho cheapie Eaten Alive. Henkel rewrote the script to add more eccentric characters and story-points, while Hooper immediately changed the title to Death Trap. (Rustam changed it back before the release. The movie has also been known as Horror Hotel and Starlight Slaughter.) They also brought in a cast that mixed Hollywood veterans like Mel Ferrer and Carolyn Jones with modern B-movie weirdoes like Chain Saw star Marilyn Burns, De Palma favorite William Finley, and newcomer Robert Englund—the latter of whom delivers the memorable first line, “My name’s Buck, and I’m rarin’ to fuck.”

Very quickly, Hooper realized he wouldn’t have the same creative control that he’d had in Texas. He quit the film multiple times, and whenever he was off the set, Rustam had one of his underlings fill in, usually ordering them to shoot more nude scenes. (Eaten Alive’s pacing is hampered considerably in its second half, which contains multiple interminable sequences where actresses very slowly take off their clothes in underlit rooms.) Even when Hooper was around, the production was a mess. The special effects were shoddy, the low-rent Hollywood soundstage was falling apart, and the lead actor Neville Brand—playing a psychotic hotelier who feeds his guests to a giant crocodile—got so into his role that he became physically and emotionally assaultive to his co-stars, on- and off-screen. And as would become typical, Hooper’s mumbly, elliptical directing style left his cast and crew unsure if he was all there. When the film flopped, his reputation as a young genius took a hit, and Universal reconsidered its contract.

Nevertheless, there are plenty of scenes scattered throughout Eaten Alive that are clearly the work of Hooper and Henkel—including that opening bit with Englund, where his character is so vulgar and obnoxious to a prostitute that he drives her to quit her bordello and flee to her fate as crocodile-chow. In an interview on Arrow’s Blu-ray special edition of Eaten Alive, Englund says that he actually adjusted easily to Hooper’s approach, which he describes as the director saying three cryptic things, one of which would make perfect sense. Elsewhere in the commentary tracks and interviews, Finley and other folks who worked on the film say that once they learned to trust him, it was obvious Hooper had a vision for the picture. He constructed the physical manifestation of a nightmare in an artificial space, and he encouraged his cast to be just as off-putting and phony.

Hooper’s intentions for Eaten Alive are plainer if you jump ahead a few years to the only Universal film he made, 1981’s The Funhouse. The studio had actually nixed its Hooper deal by then, but he happened to be attached already to the project when Universal signed on. The subsequent boost in budget payed for an elaborate set, a strong cast, a full orchestral score by veteran composer John Beal, and a cinematographer (The Warriors’ Andrew Laszlo) with a knack for illuminating vivid color within inky darkness. At a time when studios were releasing countless plotless slashers that treated their young characters like some psychotic’s “to-do” list, The Funhouse featured a more satisfyingly full Larry Block script, which introduces its cocky teens by watching them misbehave at a traveling carnival for the first third of the film, before the killing begins. By the time the kids lock themselves in a funhouse on a dare, Hooper has established the rank atmosphere of the midway—with its animal abnormality exhibits and peep-show tents—and the tragic life of its killer, Gunther, a misshapen mutant in a Frankenstein monster mask.

What Hooper really brings to The Funhouse is a willingness to make his audience feel uncomfortable, not just jolted. As with Eaten Alive, Hooper plays with the uneasy artificiality of horror movies, beginning with an opening scene that spoofs Halloween and Psycho by having a kid in a clown mask surprise his naked sister Amy in the shower with a rubber knife. Later, Amy and her friends watch from above as Gunther kills the carnival’s fortune teller after an embarrassing sexual encounter. Rather than continually cutting back and forth between the voyeurs and what they’re seeing, Hooper holds on the pathetic sex and murder for so long that the audience forgets the larger frame; and then he finally pulls back to remind us that we’re seeing all this through the eyes of youngsters, getting more than the cheap thrill they were seeking. Throughout The Funhouse, Hooper toys with our own morbid curiosity, taking seemingly fun, mild mischief and then curdling it into something sad and dangerous.

The relative restraint of The Funhouse—at least in comparison to The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and Eaten Alive—was presaged by Hooper’s work on the 1979 CBS miniseries Salem’s Lot, a two-part, three-hour Stephen King adaptation that eschewed the director’s usual outsized grotesquerie in favor of calm, careful character-building and a smattering of nerve-jangling vampire attacks. In the commentary track on Warner Bros.’s recent Salem’s Lot Blu-ray, Hooper suggests that what connects the TV movie with his other work is his career-long intention to engage the audience by confusing and upsetting them. “If they’re thinking, that means involvement,” Hooper says, by way describing how he brought Paul Monash’s screenplay to life with some of the most strikingly frightening images that had ever aired on television at that point. The shots of pale floating children, red-eyed wastrels, and hissing bat-men are often introduced before they’re explained, leaving viewers to connect the dots as to what’s happening, while in a mild state of panic.

Anyone who suggests that Poltergeist represents only the vision of Steven Spielberg should take a second—or first—look at Salem’s Lot and The Funhouse. Yes, Spielberg co-wrote and produced Poltergeist, and was reportedly on-set for much of it, serving as the final arbiter whenever the cast and crew were baffled by what the muttering Texan wanted them to do. But the first third of the film could easily pass for for a Hooper picture if no one had ever known about Spielberg’s involvement, given that it’s basically one freaky, slyly humorous moment after another, presented with minimal context.

In the interviews and Hooper commentaries on the DVD and Blu-ray editions of his films, he admits that he has a foggy memory, which makes piecing together the facts of his checkered Hollywood past difficult. On The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 Blu-ray, Hooper insists that after Poltergeist he and his friend Kit Carson (screenwriter of Paris, Texas) shopped the Chain Saw sequel around with no success for a while, before landing at Cannon. Other reports have Cannon insisting on another Chainsaw in exchange for letting Hooper make Lifeforce and Invaders From Mars. Whatever the origins of the three-picture deal, it would end up representing Hooper’s last hurrah, as well as the most prolific and creative few years of his career.

In a way, the Cannon films form a loose trilogy, unified by style and influence as much as content. The company’s bosses Yoram Globus and Menahem Golan gave Hooper the money to work on a larger scale (if not quite Poltergeist-level), and he responded by hiring some of the most talented young makeup, set-design, and effects people in the business at the time. Lifeforce’s effects were overseen by Star Wars tech John Dykstra. Invaders From Mars used Stan Winston’s team just a few months before they moved on to James Cameron’s Aliens (for which Winston won an Oscar). Chainsaw 2—easily the goriest film Hooper’s ever made—benefits from the imaginative splatter of Tom Savini. Lifeforce also has a Henry Mancini score, 70mm cinematography from Return Of The Jedi’s Alan Hume, and a screenplay co-written by Alien’s Dan O’Bannon (who also co-wrote Invaders From Mars with the same collaborator, Don Jakoby).

The problem—at least from Cannon’s point of view—is that while Hooper was evolving as a craftsman and artist, he was moving away from what the horror fans of the mid-‘80s expected. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre emerged from an era of grubby drive-in fare, and out-grubbed the competition. Salem’s Lot, The Funhouse, and Poltergeist dwelled in the same neighborhood as Halloween, Friday The 13th, and other atmospheric, cinematic slashers. But by 1985, the multiplexes had been flooded for years with scary movies that were dumb, vulgar, and gross, pandering to the same teen market that ate up Porky’s and MTV videos. Lifeforce and Invaders From Mars in particular are self-conscious throwbacks to the more theatrical and expressionistic genre pictures of the ‘50s and ‘60s.

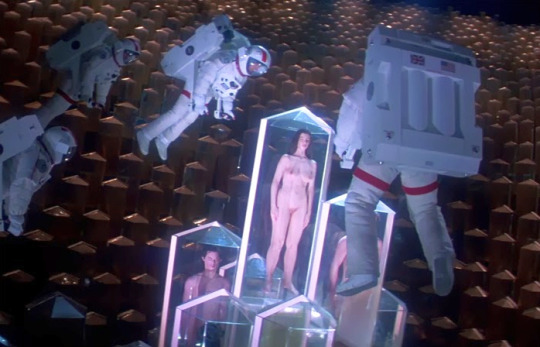

Lifeforce, based on the Colin Wilson novel The Space Vampires, begins with mind-blowing interstellar sequences inspired by Stanley Kubrick’s 2001, then moves down to the countrysides and cities of the United Kingdom for an extended homage to Hammer horror, complete with vivid matte paintings and creature puppetry, and a frequently nude villainess (played by Mathilda May) who sucks the life out of her victims. Invaders From Mars remakes William Cameron Menzies’ 1953 science-fiction/horror classic, refashioning its story of alien impostors and the little kid who fights them into a critique of Steven Spielberg’s post-hippie positivism. Invaders is stylish as all get-out, with lighting effects copied from arena-rock concerts, and swooping camera moves choreographed by Chain Saw’s Daniel Pearl. But it’s primarily interesting for how Hooper makes Spielbergian suburbia into the enemy, finding menace in the manicured backyards and clean-cut community leaders. Lifeforce too is ultimately less a monster movie than it is a study of the cultural entropy that allows ancient evils to endure.

Both those films are ultimately too clunky to call “great,” though they did find a devoted audience later on home video, as devotees of ambitious production design and subversive content realized what they’d missed. A similar reevaluation happened with The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2. It was initially dismissed by fans of the original as too slick and too silly, with unnecessary padding-out of the Leatherface family history, and a “sell-out” addition of an actual star in Dennis Hopper (albeit one who’d been on the skids until he appeared in Chainsaw 2, River’s Edge, Blue Velvet, and Hoosiers, all in 1986). Even the “corrected” spelling of “chainsaw” smacked of betrayal. But the movie became another massive hit on VHS, as gore-hounds gradually separated it from its predecessor and saw it as its own entity, graced with hilariously profane Carson dialogue—like, “Lick my plate you dog dick!”—and cartoonishly disgusting makeup effects.

More to the point, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 is a culmination of everything Hooper had been trying to do since 1974. The Leatherface clan’s underground lair beneath an abandoned amusement park recalls the gothic sets of Eaten Alive and The Funhouse, with a depth-of-field that almost looks 3-D. Caroline Williams’ performance as the plucky reporter “Stretch” Brock—whom Leatherface develops a crush on—moves a lot of the psychosexual subtext of 1980s horror to the surface, particularly in a scene where she tries to placate her attacker by coaxing him to press his weapon into her crotch. And the plot plays up the heat and violence of Texas a lot more than the first film, making the cannibals more of a typical, even respectable family, who believe they have the right to kill, skin, and eat whomever they want.

It’s harder to make a case for Hooper’s post-Chainsaw 2 work, which is dominated by forgettable straight-to-video misfires, generic work-for-hire hackery, and TV anthology episodes. It’s also tough to explain why he fell off so dramatically. Some people who’ve worked with Hooper complain in interviews that on the set he’s either vague and uncommunicative or angry that no one’s reading his mind and giving him what he really wants. But a lot of actors and technicians have collaborated with him multiple times, and describe him as a fun guy, and an inspiring leader. One of his main issues, career-wise, is that he doesn’t seem to have much of a knack for selling himself or his work—which may be why so many of his later films are billed as “from the director of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and Poltergeist,” with no mention of Salem’s Lot, The Funhouse, or Invaders From Mars (or even Chainsaw 2).

Yet for a director who’s primarily known for two films—one of which is usually credited to someone else—Hooper was responsible for a surprisingly hefty number of unforgettable scenes and images between 1974 and 1986. Leatherface’s chainsaw twirl in Chain Saw, the sudden lunges of “the master” in Salem’s Lot, the whispering television static in Poltergeist, the freshly cut skin-mask in Chainsaw 2 (and Stretch saying, “Is it wet? It’s wet!” as Leatherface puts it on her)… These are moments that any horror filmmaker can be proud of. They’re all of a piece, reflecting his preference for movies that demand a reaction, even if it’s visceral dislike.

One of his best shots is also one of his least celebrated: It’s a long take in The Funhouse of Gunther edging toward a frightened woman in a ventilation shaft, while she vainly offers to ease his sexual frustration in exchange for her life. The failed seduction is disturbing. But what’s worse is the way that Hooper holds on it for so long, keeping the monster and his intended victim in the frame—and, as always, forcing us to reckon with both.