'All the King’s Men’: Your Guide and Non-Guide to the Post-Election United States by Steven Goldman

By Yasmina Tawil

It’s shocking to realize we don’t have a good collection of cinematic equivalents to help us navigate the difficult post-election interregnum of 2016-2017. We have celebrations of democracy by the dozen and more dystopias than you can count, most of them science-fiction films more interested in dealing with the action possibilities created by political failure than with politics and governance. We also lack films that, depending on your political orientation, sincerely celebrate an ascendant American right wing or picture the United States on the edge of dystopia as a result of that same ascendency. Nor, for that matter, do we have too many films exploring either outcome as the result of a triumphal liberalism.

At the risk of employing an overbroad shorthand, whether embracing a point of view for or against their subjects, such films would be exploring the potential for an American fascism, which from certain perspectives is indistinguishable from the triumph of an American democracy. The word “triumph” is used pointedly, for this is one subtle but important message of Leni Riefenstahl’s 1935 Nazi propaganda masterpiece The Triumph of the Will. The overarching theme is of the deification of Adolf Hitler and a display of power and unity meant to restore Germany’s reputation after the supine years that followed the Great War, but the images themselves contain a warning: There are 700,000 people at this rally. This is a mass movement, and what is democracy but a mass movement? Democracy, freedom of thought and choice, the lasting gift of the Enlightenment, contains the seeds of its own destruction.

Thus did Benjamin Franklin say, on the eve of the adoption of the United States Constitution in 1787, “This is likely to be well administered for a course of years, and can only end in despotism, as other forms have done before it, when the people shall become so corrupted as to need despotic government, being incapable of any other.” He could foresee the way the downfall of democracy would work.

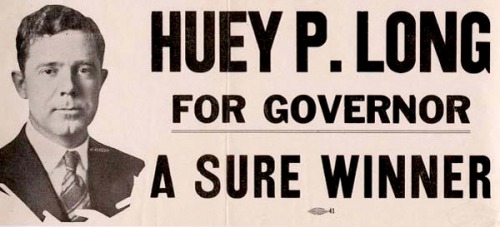

Only one major American film attempts to grapple with Franklin’s prophecy in anything like a realistic fashion and, despite winning an Academy Award for Best Picture, it makes a total hash of it. Put aside such flawed films as 1933’s Gabriel Over the White House, an outright plea for fascism in which the president is transformed by an accident into a galvanic one-man government, and Frank Capra’s 1941 classic/mess (a film can be both) Meet John Doe, which tries to have it both ways by simultaneously celebrating the goodness and gullibility of the people—only Robert Rossen’s All the King’s Men, a 1949 adaptation of Robert Penn Warren’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, takes place within a recognizable American political system utilizing characters drawn from the real world of the 1930s in its depiction of the attenuated rise of Governor Willie Stark. Modeled after Louisiana governor (later Senator) Huey Pierce Long, Stark in his cinematic form is meant to provide an object lesson in the corrupting nature of power. Consideration of both Stark and Long may help us better recognize where we are and where we may be going. If not for an assassin’s bullet, it might have been someplace we’d already visited.

Long (1893-1935) was the closest thing the United States has had to a dictator, and although his power was circumscribed by the borders of Louisiana, at the time of his death he was actively interfering in the politics of adjoining states and building a national organization that likely would have seen him try to challenge incumbent president Franklin Delano Roosevelt and split the Democratic vote in the 1936 election. The resultant repeal of Roosevelt’s Depression-fighting New Deal programs might have created enough political dysfunction that Long would have been elected by acclamation in 1940, possibly on a third-party ticket. He would have been beholden to no one in the existing power structure and imbued with dictatorial possibilities.

We’ll never know, but this was Roosevelt’s belief about Long’s maneuvers around him. What is certain is that Long’s national organization, the Share Our Wealth Society, claimed over seven million members at its peak and had been delegated to Gerald L.K. Smith, an avowed fascist and anti-Semite who was simultaneously seeking to affiliate with Hitler fan William Dudley Pelley’s Silver Shirts movement (as Benito Mussolini had Blackshirts and Hitler had Brownshirts, American fascism would be styled in argent tops) and would subsequently found the isolationist America First party to “preserve America as a Christian nation” against “highly organized” Jewish subversion. (At that moment, Jews were being highly organized into ghettos and gas chambers, but that was merely a pesky detail.) Such alliances, if Long was aware of them, would have been purely incidental to him. As he said, “I haven’t any program or any philosophy. I just take things as they come.” For Long, the means justified the end—securing and maintaining power for himself.

To understand All the King’s Men, it’s relevance to today, and where it let down as a guide to the issues it explored, even in its own time (which was contemporaneous with the rise of the House Un-American Activities Committee as a disruptive force in Hollywood and elsewhere, Richard Nixon, and Joseph McCarthy), we have to also understand Huey Long and where he and Willie Stark part ways. The Louisiana into which Long was born had long been neglected by its political establishment. In the post-Civil War world, the Republican party didn’t exist in the South. It has more life in California today than it had in the former Confederate states then. The lack of competition meant that the politicians in power didn’t really have to do anything. Sure, there were different factions within the southern Democratic Party that vied for power, but in the end, whoever won would end up cutting deals with the defeated segments to maintain the status quo. In that sense, each election was really a referendum on the distribution of graft.

The state suffered as a result. It is no insult to say it was a backwards place. As Robert J. Gordon wrote in his recent book, The Rise and Fall of American Growth, “Except in the rural South, daily life for every American changed beyond recognition between 1870 and 1940.” That is to say electrified houses? The rural South didn’t get that. Indoor plumbing? Nope. Cars instead of horses? No again, and as Warren points out more than once in the novel, most of those “horses” were actually mules. The illiteracy rate exceeded 20 percent among whites and therefore must have been appallingly high among African Americans. A state that was a patchwork of bayou and whose major city is wedged between the foot of the almost-inland sea that is Lake Pontchartrain and the Mississippi River had few bridges and almost no paved roads. New Orleans, the seat of the political old guard more so than the state capital of Baton Rouge, may have been a modern city—to a point; collusion between the government and the power utility limited even its development—but the countryside existed in a near state of nature.

No one in power cared so long as they got paid. This is the Louisiana Randy Newman sang about in the 1974 song which became an anthem in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in 2005. All of the above—Louisiana before Huey Long, the great Mississippi flood of 1927 (which is the subject of Newman’s song), and the aftermath of Katrina—are stories of the ordinary citizen being caught between hostile nature and an indifferent ruling class:

President Coolidge came down in a railroad train

With a little fat man with a notepad in his hand.

President say, “Little fat man, isn’t it a shame

What the river has done to this poor cracker’s land?”

Note that in the song President Coolidge only marvels at the destruction of the “poor cracker’s”—that is, the peasant farmer’s—land; he doesn’t offer any help. The real Coolidge didn’t even go to Louisiana when the Mississippi flooded in 1927, killing 500, displacing 700,000, and doing a billion dollars’ worth of damage. He did something worse: He sent Herbert Hoover. And Hoover, who didn’t believe government should do anything for anybody, called the Red Cross. For Louisiana, it was just more of the same, a continuation of the past and a preview of their “Heckuva job, Brownie” future. Huey Long claimed to be an alternative to all of that neglect. The problem was that no one knew if he was sincere or not.