'All the King’s Men’: Your Guide and Non-Guide to the Post-Election United States by Steven Goldman

By Yasmina Tawil

It’s shocking to realize we don’t have a good collection of cinematic equivalents to help us navigate the difficult post-election interregnum of 2016-2017. We have celebrations of democracy by the dozen and more dystopias than you can count, most of them science-fiction films more interested in dealing with the action possibilities created by political failure than with politics and governance. We also lack films that, depending on your political orientation, sincerely celebrate an ascendant American right wing or picture the United States on the edge of dystopia as a result of that same ascendency. Nor, for that matter, do we have too many films exploring either outcome as the result of a triumphal liberalism.

At the risk of employing an overbroad shorthand, whether embracing a point of view for or against their subjects, such films would be exploring the potential for an American fascism, which from certain perspectives is indistinguishable from the triumph of an American democracy. The word “triumph” is used pointedly, for this is one subtle but important message of Leni Riefenstahl’s 1935 Nazi propaganda masterpiece The Triumph of the Will. The overarching theme is of the deification of Adolf Hitler and a display of power and unity meant to restore Germany’s reputation after the supine years that followed the Great War, but the images themselves contain a warning: There are 700,000 people at this rally. This is a mass movement, and what is democracy but a mass movement? Democracy, freedom of thought and choice, the lasting gift of the Enlightenment, contains the seeds of its own destruction.

Thus did Benjamin Franklin say, on the eve of the adoption of the United States Constitution in 1787, “This is likely to be well administered for a course of years, and can only end in despotism, as other forms have done before it, when the people shall become so corrupted as to need despotic government, being incapable of any other.” He could foresee the way the downfall of democracy would work.

Only one major American film attempts to grapple with Franklin’s prophecy in anything like a realistic fashion and, despite winning an Academy Award for Best Picture, it makes a total hash of it. Put aside such flawed films as 1933’s Gabriel Over the White House, an outright plea for fascism in which the president is transformed by an accident into a galvanic one-man government, and Frank Capra’s 1941 classic/mess (a film can be both) Meet John Doe, which tries to have it both ways by simultaneously celebrating the goodness and gullibility of the people—only Robert Rossen’s All the King’s Men, a 1949 adaptation of Robert Penn Warren’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, takes place within a recognizable American political system utilizing characters drawn from the real world of the 1930s in its depiction of the attenuated rise of Governor Willie Stark. Modeled after Louisiana governor (later Senator) Huey Pierce Long, Stark in his cinematic form is meant to provide an object lesson in the corrupting nature of power. Consideration of both Stark and Long may help us better recognize where we are and where we may be going. If not for an assassin’s bullet, it might have been someplace we’d already visited.

Long (1893-1935) was the closest thing the United States has had to a dictator, and although his power was circumscribed by the borders of Louisiana, at the time of his death he was actively interfering in the politics of adjoining states and building a national organization that likely would have seen him try to challenge incumbent president Franklin Delano Roosevelt and split the Democratic vote in the 1936 election. The resultant repeal of Roosevelt’s Depression-fighting New Deal programs might have created enough political dysfunction that Long would have been elected by acclamation in 1940, possibly on a third-party ticket. He would have been beholden to no one in the existing power structure and imbued with dictatorial possibilities.

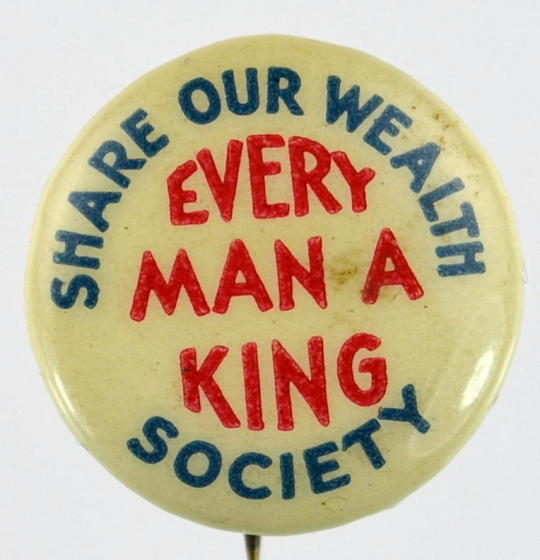

We’ll never know, but this was Roosevelt’s belief about Long’s maneuvers around him. What is certain is that Long’s national organization, the Share Our Wealth Society, claimed over seven million members at its peak and had been delegated to Gerald L.K. Smith, an avowed fascist and anti-Semite who was simultaneously seeking to affiliate with Hitler fan William Dudley Pelley’s Silver Shirts movement (as Benito Mussolini had Blackshirts and Hitler had Brownshirts, American fascism would be styled in argent tops) and would subsequently found the isolationist America First party to “preserve America as a Christian nation” against “highly organized” Jewish subversion. (At that moment, Jews were being highly organized into ghettos and gas chambers, but that was merely a pesky detail.) Such alliances, if Long was aware of them, would have been purely incidental to him. As he said, “I haven’t any program or any philosophy. I just take things as they come.” For Long, the means justified the end—securing and maintaining power for himself.

To understand All the King’s Men, it’s relevance to today, and where it let down as a guide to the issues it explored, even in its own time (which was contemporaneous with the rise of the House Un-American Activities Committee as a disruptive force in Hollywood and elsewhere, Richard Nixon, and Joseph McCarthy), we have to also understand Huey Long and where he and Willie Stark part ways. The Louisiana into which Long was born had long been neglected by its political establishment. In the post-Civil War world, the Republican party didn’t exist in the South. It has more life in California today than it had in the former Confederate states then. The lack of competition meant that the politicians in power didn’t really have to do anything. Sure, there were different factions within the southern Democratic Party that vied for power, but in the end, whoever won would end up cutting deals with the defeated segments to maintain the status quo. In that sense, each election was really a referendum on the distribution of graft.

The state suffered as a result. It is no insult to say it was a backwards place. As Robert J. Gordon wrote in his recent book, The Rise and Fall of American Growth, “Except in the rural South, daily life for every American changed beyond recognition between 1870 and 1940.” That is to say electrified houses? The rural South didn’t get that. Indoor plumbing? Nope. Cars instead of horses? No again, and as Warren points out more than once in the novel, most of those “horses” were actually mules. The illiteracy rate exceeded 20 percent among whites and therefore must have been appallingly high among African Americans. A state that was a patchwork of bayou and whose major city is wedged between the foot of the almost-inland sea that is Lake Pontchartrain and the Mississippi River had few bridges and almost no paved roads. New Orleans, the seat of the political old guard more so than the state capital of Baton Rouge, may have been a modern city—to a point; collusion between the government and the power utility limited even its development—but the countryside existed in a near state of nature.

No one in power cared so long as they got paid. This is the Louisiana Randy Newman sang about in the 1974 song which became an anthem in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in 2005. All of the above—Louisiana before Huey Long, the great Mississippi flood of 1927 (which is the subject of Newman’s song), and the aftermath of Katrina—are stories of the ordinary citizen being caught between hostile nature and an indifferent ruling class:

President Coolidge came down in a railroad train

With a little fat man with a notepad in his hand.

President say, “Little fat man, isn’t it a shame

What the river has done to this poor cracker’s land?”

Note that in the song President Coolidge only marvels at the destruction of the “poor cracker’s”—that is, the peasant farmer’s—land; he doesn’t offer any help. The real Coolidge didn’t even go to Louisiana when the Mississippi flooded in 1927, killing 500, displacing 700,000, and doing a billion dollars’ worth of damage. He did something worse: He sent Herbert Hoover. And Hoover, who didn’t believe government should do anything for anybody, called the Red Cross. For Louisiana, it was just more of the same, a continuation of the past and a preview of their “Heckuva job, Brownie” future. Huey Long claimed to be an alternative to all of that neglect. The problem was that no one knew if he was sincere or not.

Long expressed a lifelong interest in the poor and middle class, but also a lifelong ambition for political power. The maldistribution of wealth was his constant theme, first expressed publicly when he was still in his 20s. He would say that if one percent of the people consumed 99 percent of the resources, then 99 percent of the people had to survive on one percent of the resources. He had countless variations on this theme:

God invited us all to come and eat and drink all we wanted. He smiled on our land we grew crops of plenty to eat and wear… [But then] Rockefeller, Morgan, and their crowd stepped up and took enough for 120 million people and left only enough for 5 million for all the other 125 million to eat. And so many millions must go hungry and without those good things God gave us unless we call on them to put some of it back.

Long would eventually have a program to redistribute wealth in this country, a bold stance even in the Great Depression—anything that sounded like socialism or communism was feared and distrusted by the mainstream. Nevertheless, he insisted, “None shall be too big, none shall be too poor. None shall work too much, none shall be idle.” He framed this as a question of class struggle, right from the very beginning. “With wealth concentrating, classes become defined,” he wrote when he was 24. “There is not the opportunity for Christian uplift and education and cannot be until there is more economic reform.” As one of his slogans, borrowed from William Jennings Bryan, put it, “Every man a king, but no one wears a crown.”

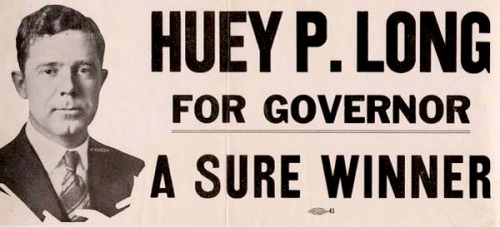

This was a fresh idea in national politics, but was as much a vehicle for Long’s own rise in the world as a sincere desire to better the lives of the non-wealthy classes. Long liked to say he was born in a log cabin, but it was kind of a nice, built-out log cabin, more or a log house, really, and if his family was far from rich, it was still comfortably situated relative to its community. Still, Long lacked the money to stick in college, and after some short stints at other institutions and a spell as a traveling salesman, he convinced Tulane to let him sit for the bar exam despite having put in only a year of study. He passed easily. From the moment he passed the bar, he said, he was running for office. In his mind, he had already been running. His siblings noted he had almost no appetite for doing physical work around the family farm and devoted more energy to nurturing his feeling that, as one remembered, “He was a man of destiny who was put here for a purpose.” He was still a teenager when he met his future wife, Rose McConnell. Soon after, she noticed he had an odd habit. As she later related to Long’s primary biographer:

He would write frequent letters on any pretext to United States senators. Naturally intrigued, she asked him why he did it. “I want to let them know I’m here,” he explained. “I’m going to be there myself someday.” …A little later he listed for her the offices he intended to occupy in progression—first, he would win a secondary state office; next, he would be elected governor; third he would go to the Senate; and finally and inevitably, he would become President. “It almost gave you the cold chills to hear him tell about it,” said Mrs. Long, shivering slightly… “He was measuring it all.”

Except for the last step, prevented by Long’s murder, this was pretty much what happened. At 24, Long was too young to run for most Louisiana offices, but he noticed that the state Railroad Commission didn’t have an age barrier. He won election to that body, which supervised utilities as well as railroads and immediately became a force in state politics, fighting Standard Oil, the real power in the state, calling the company an octopus and its executives, “the nation’s most notorious and leading criminals.”

From there, it was a short hop to the governor’s mansion in 1928. Long ran on a platform of changing the state tax code to make corporations carry more of the load and other reform-minded ideas. Once elected, he wasn’t like the previous political hacks who ran on reform platforms and then temporized once in office. Long actually did things. He provided textbooks to every school in the state, public and private; opened night schools to educate adults who might never have been to school; and pushed Louisiana State University into becoming a high-quality institution. He built free hospitals to give an impoverished populace a public health infrastructure. In a state that no one had bothered to pave, he created miles of roads and several dozen bridges. And, perhaps not least, he abolished the poll tax so as to extend the franchise to poor whites. (African Americans, alas, were still disenfranchised by other means.) Various other public works projects, such as a huge new statehouse, didn’t have much of a long-term point, but they were, on a small scale, what a state in a depression should be doing to stimulate employment.

Long paid for these programs via the traditional route of bond issues and the non-traditional one of shifting, or attempting to shift, ever more of the burden onto Standard Oil and other companies extracting resources from the state. The response of the state’s old guard was to impeach him. Long beat back the challenge by bribing 15 state senators to abort the process. That was fair, in a sense; various other senators had been bribed to support impeachment. Louisiana was the eBay of corruption.

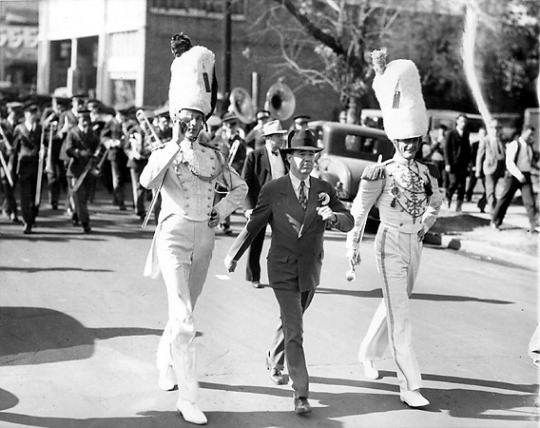

Once Long was safe, he took control of the state in a way that ensured he would never be challenged again. “I used to try to get things done by saying ‘please.’ That didn’t work and now I’m a dynamiter. I dynamite ‘em out of my path.” He began calling himself the Kingfish, after a character on the wildly popular radio show Amos ‘n’ Andy, and acted the part. His method of dynamiting can be boiled down to:

-

Patronage. He controlled every job in the state down to the school janitors. If he couldn’t cow a legislator, he could threaten the job of his sister, a teacher, and so on. This also allowed positive inducements. He could see to it that the sister was hired in the first place, or place the legislator himself on some state board that provided a second salary.

-

Graft. Long had 10 percent of the salaries of every state worker skimmed and placed in what was called the “Deduct Box.” This paid for Long’s national political activities and propaganda.

-

Flat-out kidnapping. At one point, an opponent was going to speak publicly against Long and also identify his mistress (of whom there were several). Long had him taken to a remote location for a while. When he returned, he was somehow a Long supporter. During the impeachment, he was accused of plotting the murder of an opponent as well.

-

The centralization of power. Long had the legislature pass laws that allowed the state to replace local governments that refused to go along with his plans. The state’s version of checks and balances had become so dysfunctional that the legislature was passing bills without even knowing what was in them. In one session, the legislature passed 44 bills in just over two hours. “The end justifies the means,” Long said. “I would do it some other way if there was time or if it wasn’t necessary to do it this way.” When a legislator put a copy of the state constitution in his hands, Long said, “I’m the constitution around here now.”

-

Extensive use of propaganda. Long was one of the first American politicians to grasp the possibilities of mass media. He made frequent use of the radio, originated the use of sound trucks at his rallies so he could reach more listeners, and had his own pet newspaper, which was paid for by proceeds from the Deduct Box.

-

Brazen “I dare you to call me on this” acts. For example, when Long wanted to replace the governor’s mansion and the legislature was slow to cooperate, he grabbed a bunch of convicts from the state penitentiary, handed them sledgehammers, and told them to demolish the place.

Unable to succeed himself as governor, he had himself elected to the U.S. Senate in 1930 but kept both jobs until he could engineer the election of a pliable successor who would allow him to continue running the state. Then he went to Washington and positioned himself to challenge Roosevelt. FDR tried to win him over, but in the end, he told an advisor that Long was one of the two most dangerous men in America, the other being Army Chief of Staff Douglas MacArthur. The general represented the possibility of a right-wing coup, Long the left.

“Let no one tell you that it is difficult to redistribute the wealth of this land,” Long said. “It is simple.” Hodding Carter, a Louisiana journalist and editor who was a dedicated anti-Long man to the extent he once took up arms against him, summed up the Share Our Wealth program this way: “A limitation of fortunes to $5,000,000; an annual income minimum of $2,000 to $2,500 and a maximum of $1,800,000; a homestead grant of $6,000 for every family; free education from kindergarten through college; bonuses for veterans; old-age pensions, radios, automobiles, an abundance of cheap food through governmental purchase and storage of surpluses.”

The math changed whenever Long spoke but never made any sense in any version; you couldn’t wring enough cash out of the rich to raise up the poor to that extent. The details, of course, would have been beside the point. “They think I’m so smart,” Long once said privately. “Maybe I’m not. Maybe it’s that there are a lot of dumb people in the world.” He was in basic sympathy with the Hitler-Goebbels idea of the Big Lie: Tell the people something they want to hear, the more incredible the better. They won’t check you.

FDR agreed. “Long plans to be a candidate of the Hitler type,” he said privately. He thought Long would fracture the New Deal coalition, ensuring a Republican winning the White House in 1940. Due to their laissez-faire philosophy, the Republicans would be unable to ameliorate the effects of the Depression. “That,” Roosevelt concluded, “would bring the country to such a state by 1940 that Long thinks he would be made dictator.” At about that time, Long was over at the Capitol, jokingly telling his colleagues, “Men, it will not be long until there will be a mob assembling here to hang Senators from the rafters of the Senate. I have to determine whether I will stay and be hung with you or go out and lead the mob.” No one laughed.

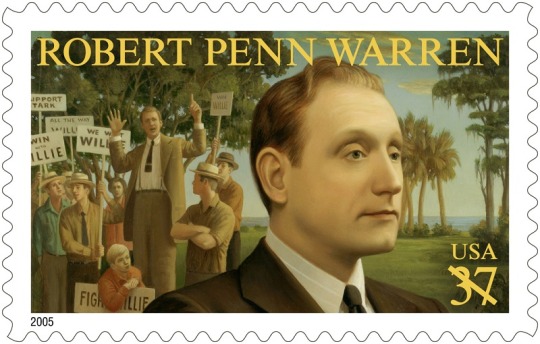

Watching all of this was Robert Penn Warren, a poet, novelist, and playwright then teaching at Tulane. The book that resulted won the Pulitzer Prize and is routinely listed among the best American novels in history. Goodreads has it ranked #58. David Handlin of The American Scholar listed it among the 100 best American novels published between 1770 and 1985. Time placed it among the 100 best English-language novels published since 1923. Book Riot placed it in the top 100 published from 1893-1993. The Guardian thinks it one of the 100-best novels written in English. The Modern Library list has it at No. 36, wedged between William Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying and Thornton Wilder’s The Bridge of San Luis Ray.

Briefly, the novel is the story of Jack Burden, an ex-reporter who is working for Willie Stark, the governor of an unnamed Southern state (pretty clearly Louisiana) as a right-hand man and fixer. Self-educated and slovenly but mentally sophisticated, Stark’s motto is “My study is the heart of the people,” but his real study is how to maintain his hold on power. When the elderly former state attorney general Judge Irwin comes out against the governor, Stark sends Burden to delve into Irwin’s background for some useful piece of blackmail. Irwin was something of a foster father to Burden, and he protests that the judge is clean. Stark disagrees: “Man is conceived in sin and born in corruption and he passeth from the stink of the didie to the stench of the shroud. There is always something.” Stark’s insistence causes Burden to immerse himself in his own past as well as the judge’s, and the more he discovers about both, the more collateral damage he and other characters suffer and the more he is forced to reevaluate his own beliefs.

Many summaries of the book refer to Stark as the main character, but in fact it is Burden, the first-person narrator. Stark is a catalytic that acts to change Burden, but undergoes no evolution himself and his perspective is never directly experienced. In short, as a novel All the King’s Men is Citizen Kane if the reporter was investigating the meaning of his own “Rosebud” instead of Charles Foster Kane’s. Demagogic politics and the Huey Long story are the environment in which Burden’s story takes place and motivates his self-searching, but are not in and of itself the point. To drive this home, the novel comes to a dead stop in the middle so that Burden can flash back to writing his graduate thesis, the story of a distant relative prior to and during the Civil War, whose experiences are an exact allegory for what Burden is going through.

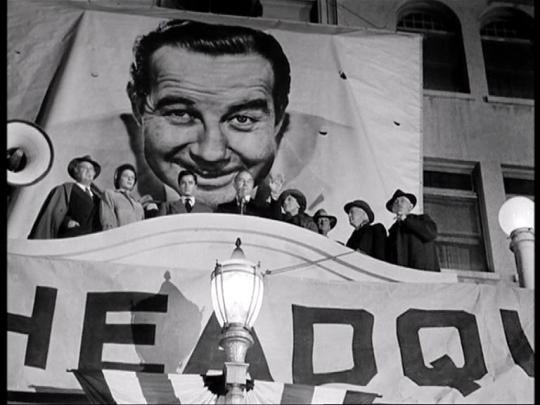

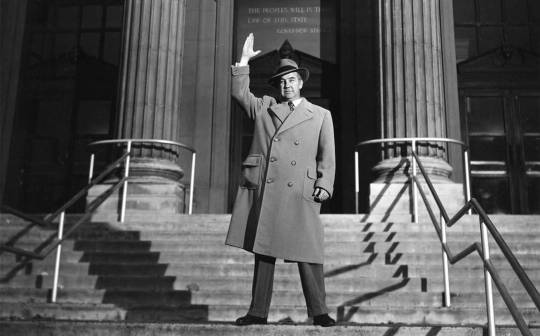

The Civil War interlude is actually the best-written and most compelling part of the book, but since it’s so far off the trunk of the main plot, naturally screenwriter-director Robert Rossen lifted it right out when it came time to make the film for Columbia Pictures. This was probably inevitable regardless of which director, writer, or studio had gotten hold of the property—the Civil War interlude was a problem for the book’s original editors, the novel’s first British edition left it out altogether, and staged adaptations have done without it as well—but Rossen never found anything to replace it as the center of Burden’s story. The result is that the film of All the King’s Men doesn’t belong to any character at all. There wasn’t enough Stark material in the novel to make him the focus, Rossen didn’t invent any either, and despite receiving a Best Actor award for his portrayal, Broderick Crawford couldn’t find any depth in an underwritten character whose despotism is more alluded-to than dramatized. Burden (John Ireland) is still present as voice-over narrator, and though some viewers have been willing to see his ethics evolve over the course of the film, the arc of his character is barely sketched in.

This presents a huge problem for a film that is supposedly depicting the way an unprincipled leader might corrupt our politics and receive his comeuppance. The film does little to engage directly with Crawford’s political process except to indicate that he’s a slob in his comportment (he drinks and takes food off of other people’s plates) and that he’s willing to use Burden for what today we would call “oppo research.” The viewer is given silent montages of him haranguing voters and legislators (in 1949 this would have been a clear allusion to Hitler) with the same footage reused more than once. Instead, in both book and film the observer is supposed to understand his corruption through the way the better people, the snobs of the patrician old guard, react to him. They are shocked and appalled that there might be corruption going on in Louisiana, a very convenient case of amnesia given that this same political class had been running the state for their own benefit for years.

In the novel, the realization that it’s not just Stark but everyone who came before him who is corrupt sends half the characters into irreversible tailspins of disillusionment and triggers the book’s denouement. This requires spectacular naiveté on the part of the characters that is not believable. In the film, these developments are simply unmotivated.

It’s tempting to assign the film’s shortcomings to its production company. King’s Men arguably never should have been at Columbia at all. Into the 1940s, there was an informal bifurcation of Hollywood studios into a “Big Five” that included MGM, Paramount, Twenty Century-Fox, RKO, and Warner Bros., and a “Little Three,” containing Universal, United Artists, and Columbia. For Universal and Columbia, part of being relegated to the minor leagues was their lack of vertical integration: They owned few or no theaters. This helped protect them from the upheaval of 1948, when the United States Supreme Court forced the studios to divest of their theatre chains. Columbia had nothing and therefore lost nothing. More importantly, under production director Harry Cohn, Columbia kept things cheap and put out a more inconsistent product than the Big Five.

One thing Columbia largely didn’t do is bid on big properties. Going back to 1920, 13 of the 25 Pulitzer Prize fiction winners had been filmed more or less contemporaneously, some multiple times. MGM had five (most famously Gone With the Wind via David O. Selznick). Even RKO, always just hanging in there, had two. Columbia had none. The closest they came was adapting two Pulitzer Prize winners for drama, Craig’s Wife (1936) and You Can’t Take It With You (1938). Here too they trailed the major studios, with MGM making six such adaptations, Warner Brothers five, and Paramount four. What Columbia did was series: It had the Three Stooges (190 shorts), Blondie (28 films), Boston Blackie (14 films), The Whistler (eight films), Crime Doctor (10 films), and The Lone Wolf (19 films). Rita Hayworth musicals didn’t have a continuing character, but they constitute a series of a kind. Cohn liked dependable properties, not risky prestige vehicles. The studio didn’t even make a Technicolor film until 1943, and that was a safe Randolph Scott western.

Hollywood noticed. There were 21 years of Academy Awards prior to 1949. Columbia had 10 Best Picture nominations in that time, and two wins: It Happened One Night, 1934, and You Can’t Take It With You. MGM had had 38 Best Picture nominations, Warner Brothers 26, Paramount and RKO 19 each, and so on.

Both of Columbia’s winning films were directed by Frank Capra. He personally was responsible for six of the 10 nominations, George Stevens for another two (The Talk of the Town, 1942, and The More the Merrier, 1943). Capra’s creative well began to dry (the unsolvable puzzle of ending Meet John Doe seems in retrospect a sign), and he left to make propaganda films for the war effort, as did Stevens. After the war ended, the two teamed up with fellow director William Wyler to form their own production company.

Without Capra and Stevens, the studio spent a few years trying to find itself. Rossen was one of the new faces given a shot at putting Columbia back on a firm creative footing. He had written some notable films for Warner Bros, including The Roaring Twenties (Raoul Walsh, 1939) and A Walk in the Sun (Lewis Milestone, 1945) and was now trying to establish himself as a director. He had two pictures under his belt, 1947’s crime story Johnny O’Clock, with Dick Powell, and the boxing film Body and Soul with John Garfield, when the rights to King’s Men became available. Depending on the source, Rossen either bought the rights himself and then made a deal with Cohn or begged Cohn to buy them and let him write, direct, and produce. Cohn, who liked Rossen, acceded, but neither had the background to make much more than a B picture.

Writing King’s Men, Rossen encountered a political riptide of criticism from voices on both the right and left, and one suspects the book was only available to Columbia because its subject matter was too controversial for the conservative likes of L.B. Mayer or Jack Warner. A member of the Communist Party, Rossen envisioned John Wayne as Stark and sent him the script. Wayne’s far-right political sympathies were well known; that Rossen could conceive of him as a left-wing demagogue shows he recognized that the goals of left- and right-wing movements may differ but the optics can be painfully similar. Unfortunately, the Duke wasn’t buying. In fact, he was disgusted. In a 1971 Playboy interview he remembered, “Every character who had any responsibility at all was guilty of some offense against society. To make Huey Long a wonderful, rough pirate was great, but according to this picture, everybody was shit except for this weakling intern doctor who was trying to find a place in the world,” and through his agent told Rossen to shove the script up his ass.

At roughly the same time, the Hollywood 10, already blacklisted but still exercising ideological pull, met with Rossen to criticize the script’s lack of proletarian rigor. They subjected him to an inquisition which only concluded when he abruptly walked out, telling them to, “Stick the whole Party up your ass.” Between Wayne and Rossen, this was clearly a film that invited severe rectal trauma.

Deprived of Wayne, Rossen went with Broderick Crawford, a jowly, heavy-set middle-aged film veteran who had first gained fame as the original Lennie in the Broadway production of Of Mice and Men. Since then, he’d spent most of his career in supporting roles in gangster and western films with titles like Trail of the Vigilantes and Black Angel. One wonders what Orson Welles, who was around Columbia at this time making The Lady from Shanghai might have done with the part, but with Crawford in the lead, a strictly B cast fell into place around him: Ireland, best known today for one of the most notorious scenes of coded homosexual flirting in a studio-era film for the scene in Red River in which he and Montgomery Clift admire each other’s guns, as Burden; Joanne Dru, also from Red River, and far from the best part of it, as Anne Stanton, Burden’s childhood sweetheart; Shepperd Strudwick as her brother Adam, a noted doctor; and Raymond Greenleaf in the pivotal role of the judge. Only with Mercedes McCambridge as Sadie Burke, who—the film does a poor job of explicating this—is in the impossible position of serving simultaneously as a key political advisor and disrespected mistress, did Rossen hit a home run; McCambridge plays in a different league than the rest of the film’s performers. She won a deserved Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress.

Crawford’s Oscar for Best Actor, won over such worthies as Kirk Douglas, Gregory Peck, and, yes, John Wayne (for Sands of Iwo Jima), is harder to figure. It’s impossible to overemphasize how miscast he is. In reviewing the film, Bosley Crowther of the New York Times wrote, “Mr. Crawford concentrates tremendous energy into every delineation he plays.” That is to say he’s loud. Crawford was 48 years old the year King’s was made. The period of Long’s life roughly corresponding to Stark’s journey in the film took him from when he was 24 to his death at 42. As such, it’s disconcerting to see Crawford, overweight with greying temples and looking close to retirement age, attending to his collegiate studies in law.

Crawford speaks with an accent that doesn’t belong to anywhere in particular but sounds far more New York than Louisiana or anywhere else in the American South, and his cadences are oddly stilted for a supposedly rabble-rousing politician, though that might be on Rossen. As with Huey Long, Stark is impeached. As with Long, Stark’s supporters stage mass rallies at the capitol which are either spontaneous demonstrations of popular affection, staged attempts to intimidate the legislature, or both. Once the threat abates, Stark addresses them in a torchlight speech. Rossen adds touches to the dialogue that make it spectacularly awkward:

This much I swear to you. These things you shall have: I’m going to build a hospital. The biggest that money can buy. And it will belong to you. That any man, woman, and child who is sick or in pain can go through those doors and know that everything will be done for them that man can do to heal sickness, to ease pain. Free. Not as a charity. But as a right. And it is your right. Do you hear me? It is your right.

“These things you shall have.” Huey Long didn’t talk like that. Nobody talks like that. It’s not just the words, though, but Crawford’s elongation of every period in the passage above. “I’m going to build a hospital. [A PAUSE SUFFICIENT TO GO TO THE LOBBY AND BUY MORE POPCORN.] The biggest that money can buy. [ANOTHER LONG PAUSE. HOW ABOUT GOING BACK FOR SOME RAISINETTES?]”

For all its flaws, this scene is the heart of the film and still valuable. It’s a shame that the Hollywood 10 missed it as it does indict the very idea that an elected leader could give the people anything that should have belonged to them in the first place. Stark promises the people a glorious hospital so that they might have free healthcare, and asserts various other rights: The right to a complete education, to fair taxation, to toll-free roads. He concludes, “It is the right of the people that they shall not be deprived of hope.”

Burden watches the speech with Adam and Anne Stanton, both of whom will find themselves among the King’s “Men” in the course of the film. Hearing Stark’s summation, Anne asks, “Does he mean it, Jack?” Adam answers, “That’s his bribe.” Adam’s conclusion may do a disservice to the motives of both Stark and Long, but on the whole it’s true: Even the most beaten-down people don’t just sign up to be under the thumb of a dictator. You have to offer something in return, an incentive to get them to take their eye off the ball, which is, always, their own freedom.

If the film of All the King’s Men was to shift the focus of the story away from Jack Burden to Willie Stark, it would have been helpful for it to provide a realistic origin story for the character. Unfortunately, Rossen failed to improve on Warren, who gives Stark a thoroughly risible beginning as a small-town politician who objects to a schoolhouse being built with subpar bricks purchased through a kickback scheme. When the schoolhouse collapses, killing or injuring several children, he gains statewide notoriety. His “fall” from that place into Longism is not realistically dramatized, or realistic in any sense. Long was a megalomaniac, and his career was not a fall from a higher state of politics but a fulfillment of his nature. That reality is much more frightening: As Willie Stark himself says, man is born in corruption.

“Megalomaniac” is a melodramatic term, but an apt one. Perhaps all presidential candidates are touched by the disease. That is not to say they are possessed by it to the degree Hitler was, but that the very nature of their desires indicate an abnormality. In 1986, the British fantasist Alan Moore wrote this dialogue for the character John Constantine: “Me? I’m just an ordinary person with ordinary needs: Food, shelter, sleep, sex, recreation, and a safe world to enjoy it all in. That’s all most ordinary people want, all us poor, uncomplicated buggers. We’re harmless. It’s all the extraordinary people who are dangerous. The ones who wake up thinking, ‘Will I conquer Europe today?’ instead of ‘What’s for breakfast?’ That sort needs warning.” People who wake up thinking, “Sure, I could be the leader of the free world with the power of life and death over millions” are possibly just as dangerous, and we’re all dependent on their motives being benign.

If those who seek power are flawed to begin with, we’d be safer judging our own susceptibility to a rising Stark or Long by looking at our own circumstances. Then and now, the governor and his fictional alter ego were defined as populist demagogues. “Populist” was also applied to the diametrically opposed presidential candidates Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders in the 2016 election. Given the loose way the term has been used, it’s important to try to define it. A populist politician is one who does his campaigning from the point of view of what is essentially class struggle, blaming elites for the problems of the masses. Those elites can be big business or a shadowy cabal of international bankers, “the establishment,” fascists, or Communists. In short, populism is about us versus them.

Thus a Trump and a Long/Stark can be two sides of the same coin. The former aimed his appeals at a sector of the electorate that felt under attack by coastal elites on a social and economic basis. It’s jobs were, it felt, being exported, people who didn’t look like them were being imported, and both were being masterminded by a corrupt leadership exemplified by Hillary Clinton, who gave secret speeches to Goldman Sachs, used her foundation to enrich herself, and cared so little for any restraints on her own self-aggrandizement that she couldn’t even be bothered to cooperate with simple regulations about government emails. Long articulated vastly different goals than Trump’s—an alteration of the basic terms of capitalism as we know them—but his approach wasn’t all that different. He too railed against a corrupt alliance of business and government that bled the middle class and the poor. The appeal of both men, running for office in times of economic dislocation, was identical: I’m going to kick the money-changers out of the Temple.

What’s most interesting about this is that in both cases, neither attracted the support of the poorest members of society. They attracted people on the bubble. Thus when we say “economic dislocation,” we have to define that, too. Long was in power from 1928 through his assassination in 1935. That is, his appeal was rooted in the heart of the most severe economic crisis the nation had ever faced, the Great Depression. The appeal of radical approaches in such a desperate environment is obvious. Trump ran in what are, relatively speaking, good times: There are few who would argue that the “Great Recession” that began in 2008 isn’t over and that we’re on to something else now; if things aren’t as good as they were, they’re surely a lot better. Yet the aftershocks are still being felt, the healing isn’t equally distributed, and some ongoing pain, like the loss of industrial and mining jobs to technological change, has been understandably misattributed by its victims to elite-originated dislocation.

Thus, what historian Alan Brinkley wrote of Long’s followers still applies: They were not the worst victims of the Depression. “In many ways they suffered less. What set them apart from many of their colleagues was that they usually had more to protect: a hard-won status as part of the working-class elite, a vaguely middle-class life-style, often a modest investment in a home… They were people with something to lose. They were, therefore, people particularly susceptible to the messages [Long] transmitted: the defense of local institutions, the excoriation of distant power centers. Such men and women sense, if only vaguely, that the networks of local associations which gave their lives meaning were threatened by the emergence of a modern, integrated economy… What they shared was an imperiled membership in a world of modest middle-class accomplishment.”

For those who followed the last presidential election closely, those words, written in 1982, should have a vivid familiarity. They represent the foundation of the Trump movement.

Willie Stark can be no guide to our future, nor can Huey Long, for each was murdered before we could learn what happens next. In The Populist Persuasion, Michael Kazin wrote:

Populism in the United States has made the unique claim that the powers that be are transgressing the nation’s founding creed, which every permanent resident should honor. In this sense, American populism binds even as it divides… The fact that the political actors were fighting over a shared set of ideals helped Americans to avoid the terrors to body and mind that have characterized the hegemony of revolution ideologies in other nations: fascism, Nazism, Leninism, Maoism, and the type of Islam that currently rules in Iran… Through populism, Americans have been able to protest social and economic inequalities without calling the entire system into question.

Except, and this is a big except, populism never before won a national election, and its very success may obviate the safety-valve function Kazin identified. What made Long threatening is that he broke with established American norms of political behavior. The same goes for Trump, either because of the nature of his white nationalist and nativist supporters, who are out of the American mainstream (or at least were until now); because his manner of comportment, whether on the stump, in business, or with women would have heretofore placed him beyond the pale of acceptability; or because of the intuitive understanding that you can’t respect what you don’t know, and Trump clearly knows neither our history or theory of government.

In Long’s day, with Hitler and Mussolini ascendant and the nation in disarray, the obvious sequel to the Kingfish’s rise seemed to be fascism. Even before Warren had begun his Long-inspired novel, Sinclair Lewis had published It Can’t Happen Here (1935, never filmed), about a Long-like figure establishing himself as a dictator. Lewis, as always, aimed towards satire, but the scenario wasn’t unrealistic. “There is no dictatorship in Louisiana,” Long said. “There is a perfect democracy there, and when you have a perfect democracy it is pretty hard to tell it from a dictatorship.” This is the chameleon nature of fascism as alluded to in Riefenstahl, and is similar to what George Orwell concluded in 1944 as he struggled to define fascism against overbroad use of the term: “It is impossible to define Fascism satisfactorily without making admissions which neither the Fascists themselves, nor the Conservatives, nor Socialists of any colour, are willing to make.” Long concluded, “A perfect democracy can come close to looking like a dictatorship, a democracy in which the people are so satisfied they have no complaint.”

In 1935, journalist Raymond Swing identified four preconditions for the rise of fascism in the United States: “the impoverishment of the middle class; economic stagnation; the paralysis of democratic government; and the threat of a strong Communist movement.” It seems likely that any other “ist” or “ism” can be substituted for “Communist” at this late date to serve as a galvanic threat. Thus the United States of 2016 is 4-for-4 on the Swing scale. Yet Swing may have missed one other element: The presence of a demagogue to exploit the issues populism raises.

“Demagogue” is not a well-defined term either, but a useful shorthand is that a demagogue is a parasite who feeds off the needs of the people to form a mass movement for his own benefit. He himself might have galvanized that movement; it doesn’t matter. The people have fears and frustrations. The potential leader perceives those emotions and channels them into a movement that builds something. The potential demagogue channels them into the acquisition of power for its own sake, the pursuit of anti-democracy. Long’s biographer, T. Harry Williams, defined a demagogue as “one of those swaggering blusterers, those base fellow who have throughout history deceived the masses with turbulent rhetoric, cynical promises, and clownish tricks.”

It was this stick that the great editor and columnist William Allen White was gnawing at when he wrote, “Fascism always comes through a vast pretense of socialism backed by Wall Street money… Huey Long is the type we must fear. Huey Long, backed by the Wall Street money on the quiet, rabble-rousing the morons into a belief that he was going to give them pancakes three times a day, is a menace.”

Well, you might say, there are a lot of people who need pancakes. Would it be so bad to give ‘em some? The answer is, “No, of course not,” but it matters who is giving them and how and why. You can’t debauch a constitutional system to any end, altruistic or selfish, and expect it to spring back into its old shape like it was made of memory foam. Once deformed, it stays deformed.

This is an issue that All the King’s Men raises, although the film, in its eagerness to beat the story into an dull-witted morality play, nearly throws it away. It’s no surprise that an adaptation would attenuate the characters’ longer speeches from the book, but in truncating this passage of Stark speaking to Adam Stanton, bits of which are thrown away with cinematographer Burnett Guffey’s camera hugging tightly to Crawford’s right ear (Guffey would later win Oscars for shooting From Here to Eternity and Bonnie and Clyde, but he and Rossen made some bizarre choices when shooting King’s) the film misses an important point:

“Goodness. Yeah, just plain, simple goodness. Well you can’t inherit that from anybody. You got to make it, Doc. If you want it. And you got to make it out of badness. Badness. And you know why, Doc?” He raised his bulk up in the broken-down wreck of an overstuffed chair he was in, and leaned forward his hands on his knees, his elbows cocked out, his head outthrust and the hair coming down to his eyes, and stared into Adam’s face. “Out of badness,” he repeated. “And you know why? Because there isn’t anything else to make it out of.” Then, sinking back into the wreck, he asked softly, “Did you know that, Doc?”

Then the Boss asked, softer still, almost whispering, “Did you know that, Doc?”

In reacting to All the King’s Men, those critics who clearly haven’t read it distort the meaning of the title, saying the allusion to the nursery rhyme “Humpty Dumpty” is about Willie Stark, the metaphorical king (standing in for Long, The Kingfish) taking a great fall. No, nope, sorry. Warren wasn’t that on the nose. If you think too much of Humpty Dumpty himself you’ve been misdirected. The title of All the King’s Men refers exactly to who it says it does: all the men (some of whom are women) who surround, support, and enable the king. These characters, all of whom are deeply wounded in some way, are corrupted just by being in his orbit and ultimately bring about his downfall. Stark’s destruction happens not through the direct actions of any of them, but because their behaviors are dictated by the environment he creates, they make decisions that inevitably have negative consequences. They disprove the philosophy expressed above: “Out of badness” only comes additional badness.

Long, one last time: “There are all kinds of demagogues. Some deceive the people in the interests of the lords and masters of creation, the Rockefellers and Morgans. Some of them deceive the people in their own interest.” But, no. It doesn’t work that way. As the historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. told Ken Burns, “Machiavelli long ago said a great man cannot be a good man. But there are limits to the methods a great man can employ in order to do good.”

This is an important thing to understand in terms of our own choices of leaders. Morality may be a pain in the ass and coloring within the lines boring, but the rules exist to constrain the possibility of bad outcomes. To take Richard Nixon as one example, the president created a win-at-all-costs environment in which his subordinates felt empowered to undertake a series of what they called “dirty tricks.” These in turn created circumstances in which Nixon himself committed crimes (obstruction of justice, among others) which ultimately resulted in the termination of his presidency. Unfortunately, the film of All the King’s Men does away with all such complexities. By making Stark obviously, loudly corrupt and the King’s Men shocked at his behavior, it isolates him, makes him an outlier, when in reality he’s a metastasizing cancer who causes his own great fall.

In an introduction to a later edition of his novel, Warren wrote that Stark was inspired by Huey Long, but was not meant to be him. “For better or worse, Willie Stark was not Huey Long. Willie was only himself.” Stark, Warren notes, was a symbol of “the kind of doom that democracy may invite upon itself.” That’s the kind of thing All the King’s Men could have shown us, but didn’t. As Hodding Carter wrote of Huey Long and surely would have written of Willie Stark, “Had all Americans lived some of those years under him, democracy would be more secure today, because democracy would have come to have a more precious meaning.”

BIBLIOGRAPHIC NOTE: Sources for the quotations found in this essay include Voices of Protest (Alan Brinkley), Robert Rossen: The Films and Politics of a Blacklisted Idealist (Alan Casty), The Populist Persuasion (Michael Kazin), Freedom From Fear (David M. Kennedy), The Aspirin Age (Isabel Leighton, ed.), The Politics of Upheaval (Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr.), Huey Long (T. Harry Williams).