Evil in the Mirror: John Carpenters Revealing Prince of Darkness by Joshua Rothkopf

By Yasmina Tawil

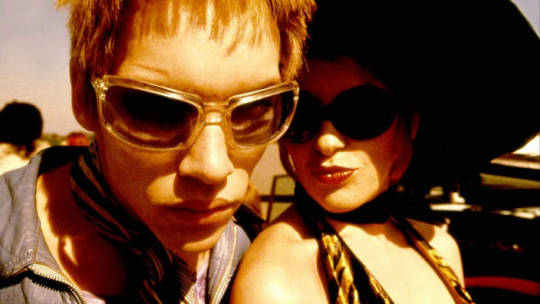

[Last year, Musings paid homage to Produced and Abandoned: The Best Films Youve Never Seen, a review anthology from the National Society of Film Critics that championed studio orphans from the 70s and 80s. In the days before the Internet, young cinephiles like myself relied on reference books and anthologies to lead us to films we might not have discovered otherwise. Released in 1990, Produced and Abandoned was a foundational piece of work, introducing me to such wonders as Cutters Way, Lost in America, High Tide, Choose Me, Housekeeping, and Fat City. (You can find the full list of entries here.) Our first round of Produced and Abandoned essays included Angelica Jade Bastin on By the Sea, Mike DAngelo on The Counselor, Judy Berman on Velvet Goldmine, and Keith Phipps on O.C. and Stiggs. Over the next four weeks, Musings will continue with another round of essays about tarnished gems, in the hope theyll get a second look. Or, more likely, a first. Scott Tobias, editor.]

Its generally accepted that John Carpenter wasnt a personal filmmakernot personal in the way that Martin Scorsese, only five years his senior and Italianamerican from the start, was. Carpenter grew up movie-crazy in the 50s and 60s. He wanted to make Westerns exactly at the moment when that became an unrealistic career goal. His heroes were Alfred Hitchcock, Orson Welles and, above all, Howard Hawks. Its been nourishing to listen to Amy Nicholsons wonderful eight-part podcast Halloween Unmasked, still in progress, and to hear Carpenterusually oblique in interviewsopen up about his boyhood in the Jim Crowera South. He mentions visiting an insane asylum during a college psych trip and locking eyes with a prisoner who spooked him. That may be the basis for killer Michael Myers but, by and large, this was a guy who wrote what he dreamed up, not what he knew.

Thats not to suggest Carpenter didnt develop his own signature style. When he arrived in Los Angeles in 1968 to attend film school at USC, he reinvented himself, transforming from a Max Fischerlike creative wunderkind (he was a rock guitarist and high-school class president) into a laconic, bell-bottomed cowboy who listened more than he spoke. He was too cool for nerdy Dan OBannon, who worked with him on Dark Star. He was too cool for Hollywood itself, even after hed succeeded there, rarely mingling socially and turning down projects like Top Gun and Fatal Attraction.

But the cool act was a bit of smokescreen. I once asked Carpenter about it, and he owned up to a private sense of pain in regard to his work. I take every failure hard, he told me in 2008, singling out the audiences abandonment of The Thing, a remake of his favorite film (one that actually improves on its source). The movie was hated. Even by science-fiction fans. They thought that I had betrayed some kind of trust, and the piling on was insane. Even the original movie’s director, Christian Nyby, was dissing me.

Carpenter would rebound from that 1982 commercial disasteras well the indignity of getting sacked from Firestarterby playing the game even better. He directed Jeff Bridges to a Best Actor nomination on Starman (thats as rare as a unicorn for a sci-fi performance) and, just as things were turning golden, blew all his capital again on 1986s Big Trouble in Little China, which was rushed and subsequently buried in the massive shadow of Aliens. You try to make a studio picture your own, but in the end, its their film, Carpenter said in our interview, the Kentucky rascal turned bitter. And theyre going to get what they want. After that experience, I had to stop playing for the studios for a while and go independent again.

This is the pivotal moment in Carpenters career, the one that fascinates me the most. It should fascinate more people, given what the filmmaker did. Divorced and with a two-year-old son, Carpenter is, at that point, 38 years old. Hes already feeling like a Hollywood burnout, with a decade of ups and downs to prove it. The solution was a pay cut, a big one: Prince of Darkness, financed through supermensch Shep Gordon and Alive Films and released in 1987, would be made for a grand total of $3 million, the first title in a multi-picture deal that guaranteed Carpenter complete creative control.

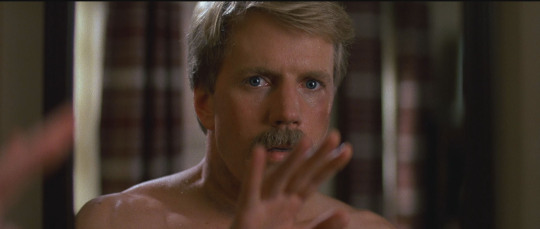

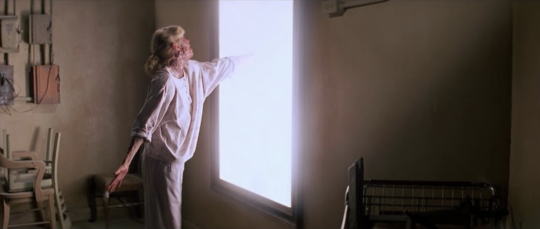

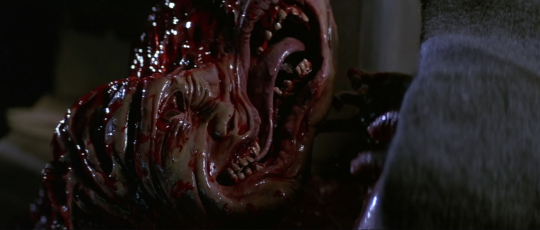

Scrappy but never chintzy, Prince of Darkness is the most lovable of movies. On the surface, it has all the cool minimalism a JC fan could ask for: elegant anamorphic compositions (Gary Kibbes muscular cinematography adds millions more in production value), a seesawing synth score, a one-location siege structure akin to the directors Assault on Precinct 13 and The Thing. The movie also has Alice Cooper killing a grad student with a bicycle. It has a swirling canister of green Satanic goo in a church basement.

Critics, by and large, were unkind. In a representative review from the New York Times, Vincent Canby called it surprisingly cheesy, singling out first-time screenwriter Martin Quatermass for particular scorn (he overloads the dialogue with scientific references and is stingy with the surprises), not realizing that this was a pseudonym for Carpenter himself. Would it have mattered? Released days before Halloween, Prince got clobbered by the gig Carpenter turned down, Fatal Attraction, still surging in its sixth weekend.

But below the surfaceand still a matter for wider appreciationis the film that Carpenter dug himself out of his psychic hellhole to make: his most personal horror movie, starring a version of himself. Prince of Darkness is about watching and waiting. In a way, its a romantic view of the auteurs own time at school. Its a movie about the evil that stares out of the mirror (i.e., yourself). Like all of his films, it arrived under the possessive title John Carpenters Prince of Darkness. In my mind, that apostrophe is actually a contraction: John Carpenter Is Prince of Darkness. And Prince of Darkness is him.