Personality Crisis: The Radical Fluidity of Todd Haynes’ ‘Velvet Goldmine’ by Judy Berman

By Yasmina Tawil

[This month, Musings pays homage to Produced and Abandoned: The Best Films You’ve Never Seen, a review anthology from the National Society of Film Critics that championed studio orphans from the ‘70s and ‘80s. In the days before the Internet, young cinephiles like myself relied on reference books and anthologies to lead us to film we might not have discovered otherwise. Released in 1990, Produced and Abandoned was a foundational piece of work, introducing me to such wonders as Cutter’s Way, Lost in America, High Tide, Choose Me, Housekeeping, and Fat City. (You can find the full list of entries here.) Over the next four weeks, Musings will offer its own selection of tarnished gems, in the hope they’ll get a second look. Or, more likely, a first. —Scott Tobias, editor.]

Like the glam rockers it gazes upon through the smoke-clouded lens of memory, Velvet Goldmine is most beautiful when it descends into chaos.

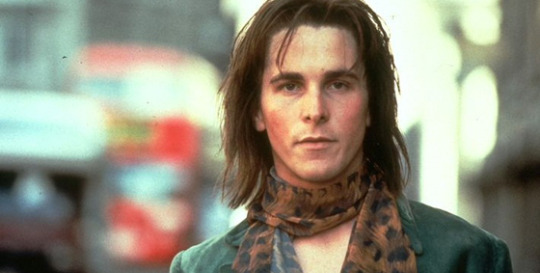

Stolen, the way great artists do, from Citizen Kane, the skeleton of Todd Haynes’ 1998 film is a chain of interlocking reminiscences of Brian Slade (Jonathan Rhys Meyers), a David Bowie-like glam rocker who fakes his own onstage death in the mid-’70s. A decade later—in that most dystopic of years, 1984—his ex-wife Mandy (Toni Collette) and former manager Cecil (Michael Feast) relate their bitter tales of betrayal to a journalist (Christian Bale) whose assignment has him reluctantly reliving his own teenage sexual awakening under the influence of Brian’s music. Between the interviews, musical numbers, and onscreen epigrams, there’s also a mysterious female narrator who sometimes surfaces, like a teacher reading a subversive storybook, with dreamy exposition that reaches back a century to invoke glam’s patron saint, Oscar Wilde.

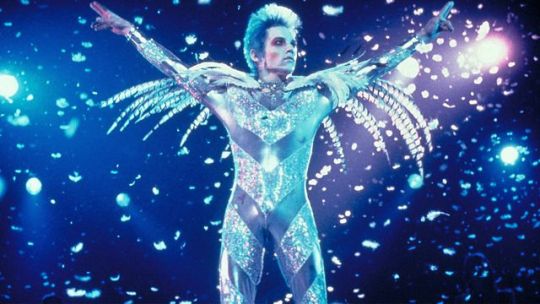

The film climaxes with a propulsive sequence of scenes that are exhilarating precisely because they merge all of these points of view, subjective and omniscient, into one collective fantasy. Brian and his new conquest, the Iggy Pop/Lou Reed composite Curt Wild (Ewan McGregor), ride mini spaceships at a carnival to Reed’s “Satellite of Love.” Two random schoolgirls, their faces obscured, act out a love scene between a Curt doll and a Brian doll. In a posh hotel lobby, Brian’s entourage, styled like Old Hollywood starlets on the Weimar Germany set of a fin-de-siècle period film, recites pilfered sound bites about art. Then Brian and Curt are kissing on a circus stage, surrounded by old men in suits. They play Brian Eno’s “Baby’s on Fire” as Haynes cuts between the performance, an orgy in their hotel suite, and Bale’s hapless, young Arthur Stuart masturbating over a newspaper photo of Brian fellating Curt’s guitar. Stripped of narration—not to mention narrative—the film seems to be running on its own amorous fumes, its story fragmenting into a heap of glittering images as it hurtles from set piece to set piece.

Visual pleasure aside, it’s a perfect way of translating into cinematic language the argument that underlies Haynes’ script—that glam’s revelations about the radical fluidity of human identity go far beyond sex and gender. As the apotheosis of teen pop audiences’ thirst for outsize personae, fictional characters like Ziggy Stardust (who Velvet Goldmine further fictionalizes as Slade’s alter ego, Maxwell Demon) melded the symbiotic identities of artist and fan into a single, tantalizing vision of hedonism and transgression. Kids imitated idols they didn’t quite recognize as pure manifestations of their own inchoate desires. Musician and fan became each other’s mirror, and both could become entirely new people simply by changing costumes or names.

But it’s pretty much impossible to imagine Velvet Goldmine’s distributor and co-producer, Harvey Weinstein, appreciating this as he watched the film for the first time—or seeing anything in it, really, besides an expensive mess.

Haynes and his loyal producing partner, Killer Films head Christine Vachon, had already been through hell with Velvet Goldmine by the time they delivered a cut to Miramax. Bowie had refused Haynes’ repeated requests for permission to use six Ziggy-era songs in the film, claiming that he had a glam movie of his own in the works. And in a production diary that appears in her book Shooting to Kill, Vachon points out one unique challenge of making a film about queer male sexuality: “The MPAA seems to have a number of double standards. Naked females get R ratings, but pickle shots tend to get NC-17s. Our Miramax contract obligates us to an R.” She also mentions that an investor pulled $1 million of funding just weeks before filming.

The shoot was even more harrowing than the two veteran indie filmmakers could’ve predicted. As they fell behind schedule, a production executive started nagging Vachon to make cuts. “Todd is miserable,” she wrote in her diary the night before they wrapped. “He says that making movies this way is awful and he doesn’t want to do it.” In an interview that accompanies the published screenplay for Velvet Goldmine, Oren Moverman asks Haynes, “Was the making of the film joyful for you?” “I’m afraid not,” he replies. “We were trying very hard to cut scenes while shooting, knowing that we were behind and we didn’t have the money for the overloaded schedule. But there was hardly a scene we could cut without losing essential narrative information.” It’s remarkable that he managed to capture 123 usable minutes’ worth of meticulously art-directed ‘70s excess (and ‘80s bleakness) in just nine weeks, under so much external pressure, on a budget of $7 million.

When the film finally reached Harvey Scissorhands, after months of editing, Weinstein told Haynes it was too long and the structure didn’t work. “He made suggestions that I didn’t follow, and then he just buried it,” the director told Down and Dirty Pictures author Peter Biskind. What happened next comes straight from the Weinstein playbook: “Even afterward,” Haynes remembered, “they threw out a DVD, they didn’t ask for a director commentary, my name wasn’t on the cover of it, it was buried in the minuscule billing block. He can’t even do the really small things that don’t cost anything—he never shows any respect.” (That Haynes never found a distributor he preferred to Weinstein, with whom he reunited for I’m Not There and Carol, speaks volumes about the way Hollywood treats ambitious filmmakers.)

After it failed to blow audiences away at the 1998 Cannes Film Festival, Miramax effectively dumped Velvet Goldmine. It debuted on just 85 screens that November, ultimately grossing about $1 million stateside. Its ridiculous theatrical trailer might well be a glimpse at the movie Weinstein was expecting: a “magical trip back to the ‘70s” with 100% more murder mystery and 100% less gay sex.

Critics were just as ambivalent about the film as festival audiences. While forward-thinking reviewers wanted to love it for its visual beauty and openly queer aesthetic, many lamented that its plot was slight and its characters hollow. David Ansen of Newsweek complained that “Haynes is unwilling to get too close to his characters. Slade, in particular, is a blank”—failing to see that Brian is a cypher by design. Like the Barbie-doll Karen Carpenter of Haynes’ debut feature, Superstar, and the fragments of Bob Dylan diffused across I’m Not There, Velvet Goldmine’s Bowie is less a portrait of the real person than a screen on which fans project their own fantasies about him.

At The Nation, Stuart Klawans rightly identified Arthur, not Brian, as the film’s protagonist. But he also wondered why he grows up to be such an unhappy adult. “Why is Haynes so tough on Arthur?” Klawans wanted to know. “Why, through the character, is he so tough on himself? It’s apparent everywhere in Velvet Goldmine that Haynes, like Arthur, loves Glitter Rock. He, too, fell for a mass-marketed product, which was no more likely than Mr. Clean to carry out a world-transforming promise. But instead of honoring the truth of his enthusiasm, so that he might look back on its object with a smile and a sigh…Haynes does penance for being a sap.”

Others found the film’s collage of ideas and allusions cumbersome. “Velvet Goldmine is weighed down with self-important messages, but it’s also splashily opulent,” Stephanie Zacharek wrote at Salon. “It’s as if Todd Haynes had plunged his hand into a pile of clothes at a jumble sale and come out with a handful that was half velvet finery, half polyester rejectables.”

All of these reactions make sense, coming from adult critics who had probably seen the film just once, after reading months’ worth of reports about its troubled birth, in the sterile environment of a press screening. But what’s clear from a distance of nearly two decades, during which Velvet Goldmine has become a low-key cult classic, is that few films are so poorly suited to be judged on the basis of a single dispassionate viewing. If you’re looking for tight plotting and complex characters, you’re not going to find them in this mixtape of music videos, aphorisms, and waking dream sequences. There is no actual murder mystery, and Arthur’s investigation into Slade’s disappearance isn’t a source of suspense so much as an excuse to keep contrasting an incandescent past with a dull, gray present.

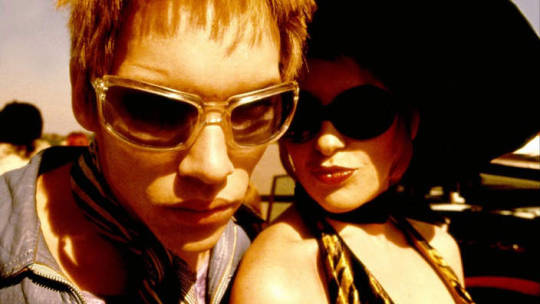

I’m lucky enough to have first encountered Velvet Goldmine under what turned out to be ideal circumstances: at age 15, on premium cable, late enough at night that it easily bypassed my rational mind en route to my adolescent subconscious. I had no idea how many details it cribbed from the biographies of Bowie and his contemporaries, or how much of the dialogue was quoted from their (and their heroes’) most memorable utterances. I bought the soundtrack without realizing that it put ‘70s originals side-by-side with contemporary covers and new songs by younger bands like Pulp and Shudder to Think in yet another glam pastiche. It wouldn’t have occurred to me to find the 1984 scenes unsatisfying because I got so instantly immersed in the ‘70s spectacles that they barely existed for me.

Not that the film only works on an emotional level. Haynes’ ideas about fandom, politics, sexuality, and identity become even more profound once you can see the organizing principle behind what might initially seem like a jumble of indulgent images. Like the death hoax Brian Slade uses to escape a fantasy life that’s grown too real for comfort, Velvet Goldmine’s loose plot is classic misdirection, obscuring a tight and purposeful structure that delays the resolution of the ‘80s storyline until it’s primed you to feel the loss of the liberated ‘70s viscerally. But you’ll never get that far into dissecting the film if you don’t fall in love with it at first viewing. And that’s easiest to do when you’re as impressionable as young Arthur, who watches Brian Slade flaunt his queerness in a televised press conference and imagines himself shouting to his parents, “That is me!”

Revisit it as you grow older, though, and you might discover that the disillusioned 30-something characters now feel as rich as their idealistic former selves. Velvet Goldmine is often called a gay film, but that obscures the universal resonance of its queer coming-of-age narrative. Better to think of it as a bisexual film that uses non-binary sexuality as a metaphor for the boundless possibilities of youth—the promise of a future constrained only by the limits of one’s own ambitions and appetites. Its characters can’t achieve permanent liberation by “coming out”; to maintain lifestyles that match their desires, they would have to reject the monogamy that defines adulthood for most people. Particularly amid the AIDS crisis of the 1980s, which haunts the film’s dreary present on a purely subtextual level, it’s obvious why they (like the real glam rockers they’re modeled after) retreat from the liberated lives they staked out for themselves.

But you don’t need to buy in to the incendiary claim Brian makes at his press conference, that everyone is bisexual, to see how this storyline reflects the many kinds of disappointments that await most starry-eyed fans in adulthood. Klawans’ objection to Haynes’ treatment of Arthur feels naive because it assumes people should be able to peacefully coexist with their shattered dreams. Why shouldn’t he feel bitter about having joined a sexual revolution that didn’t, finally, set him free? “It gets better” for Arthur when he leaves his homophobic family to move in with a latter-day glam act in London, but sometime after he hooks up with an unmoored Curt Wild at a tribute concert called the Death of Glitter, “it” just gets boring as the world gets worse.

And the world really does sometimes get worse, though audiences in the relatively peaceful, prosperous late ‘90s might have forgotten about that. Watching Velvet Goldmine for perhaps the 25th time, two weeks before Donald Trump’s inauguration, at the end of an era that has brought unprecedented freedom of sexual and gender expression, I was struck by how vividly Haynes captures a culture’s flight from progress, and how rare it is to see that kind of transition depicted on film. His argument about fluidity turns out to be even more potent when applied to societies than individuals (or, at least, it seems that way in 2017). Our capacity for transformation may be infinite, but that doesn’t mean those changes are always for the best.