Electroma or: It Became Necessary for Daft Punk to Destroy Themselves in Order to Save Their Careers By Craig J. Clark

By Yasmina Tawil

When Daft Punk’s Electroma was unveiled in the Directors’ Fortnight at the 2006 Cannes Film Festival, it was met with at best a muted response. Writing for Variety, Leslie Felperin chastised bandmates Thomas Bangalter and Guy-Manuel de Homem-Christo, who “bizarrely choose not to use their own catchy tunes here, the one thing that might have given pic slim commercial legs.” Felperin also invoked such cinematic endurance tests as Gus Van Sant’s Gerry and Vincent Gallo’s The Brown Bunny, and called the plot “risible and had aud at projection caught ankling in droves”—Variety-speak for the high volume of walkouts it inspired, which explains why its premiere received scant coverage.

A ready-made cult film with no spoken dialogue and only a handful of songs with lyrics, Electroma found its audience among the Daft Punk faithful at midnight screenings the following year, but those who missed seeing it in theaters must be willing to part with upwards of $100 if they want an unopened copy of the out-of-print Region 1 DVD. More frugal fans with a subscription to Tidal can opt for the tenth anniversary edition the band released exclusively on the streaming site last year or make do with one of the numerous versions of the film that have been uploaded to YouTube, one of which comes with an alternate soundtrack culled from Daft Punk’s own catalog. The one curated by the band and music supervisor Steven Baker is perfectly suited to the film, though, progressing from Todd Rundgren to Brian Eno to Curtis Mayfield to choir music and beyond. Their choices say a lot about how wide-ranging their musical tastes are, which would be less evident if they had merely dropped in tracks from Human After All, their then-current record.

Released in 2005, Human was the band’s much-anticipated follow-up to 2001’s Discovery, which provided the soundtrack for their first quasi-feature, the 68-minute animated sci-fi tale Interstella 5555: The 5tory of the 5ecret 5tar 5ystem. Along with the robot helmets that made their debut around the same time Discovery did, Interstella took the focus off Bangalter and de Homem-Christo as individuals and gave them another creative outlet since they co-wrote its screenplay. (The Residents—subjects of the recent documentary Theory of Obscurity—pulled off a similar feat a few decades earlier, cycling through a number of disguises in their films and live appearances before adopting the eyeball-head look that came to be their trademark.)

The urge to venture into new arenas continued with Electroma, which began life as a video for Human After All’s title track, but quickly expanded its scope to tell a complete, if simple, story about two robots and their doomed quest to become human. Hero Robot #1 and Hero Robot #2 aren’t just any robots, though, since they wear Thomas and Guy-Manuel’s signature helmets and the black leather outfits that were the band’s uniform at the time, complete with their logo spelled out in metal studs on their backs. So, even though they aren’t played by Bangalter and de Homem-Christo, who were busy enough handling directing duties (with Bangalter doubling as cinematographer), they are Daft Punk for all intents and purposes, and the scenario devised for them by Bangalter, de Homem-Christo, Cédric Hervet (also the film’s editor and script collaborator on Interstella), and Paul Hahn (also its executive producer) can be read as autobiographical if viewed from the right angle.

The film starts on colorful rock formations in the California desert, where a black Ferrari with the license plate “HUMAN” awaits our heroes. So does a fiery reckoning, which the flames under the title prefigure. There are, in fact, a number of cutaways to these flames sprinkled throughout the film, starting with the scene of Thomas and Guy-Manuel driving down an empty highway (shades of the opening car ride in Gerry) to the accompaniment of Todd Rundgren’s “International Feel.” So far, so normal, but then they pass a tractor ridden by a robot farmer with a Guy-Manuel helmet, which doesn’t prepare the viewer for the sight of a whole town where every man, woman, and child from all walks of life is a robot sporting their headgear as Rundgren’s spacy ’70s rock gives way to Brian Eno’s moody instrumental “In Dark Trees.”

In a society where everybody looks like you—or sounds like you, as many musical acts tried to emulate Daft Punk in the wake of Discovery’s chart success—what can you do to stand out? Well, here the duo continues on to a nondescript facility where technicians in all-white outfits in a white room give them a technologically assisted makeover. This takes the form of sitting Thomas and Guy-Manuel down and pouring liquid latex over their helmets and affixing pre-formed facial features and wigs to it to give them distorted human faces. As disturbing as their new look is, this is still the culmination of their misguided dream, and when they reveal it to the world, strutting down the road to Curtis Mayfield’s funky “Billy Jack,” they stop everyone that sees them in their tracks. Then the latex starts melting in the hot sun and the town’s residents drop whatever they’re doing and give chase, much like the villagers in a Universal monster movie or the pod people in Invasion of the Body Snatchers. (Echoing Human After All’s mixed reviews and status as their lowest-selling studio album, the takeaway is that nobody wants Daft Punk to be human.)

Taking refuge in a dingy gas station restroom with a flickering light, the robots shed their grotesque visages—although it would be fair to say their faces rejected them first—to the strains of Sébastien Tellier’s “Universe” (the only song on the soundtrack not to hail from the ’60s or’70s). Of the two of them, Thomas is more shell-shocked by the experience, impassively staring at himself in the mirror while Guy-Manuel angrily tears his face off and flushes it down the toilet. (For anybody looking for another Gerry analogue before the extended homage kicks in, this is Electroma’s “Fuck the thing” moment.) Then, after Thomas is snapped out of his inaction and cleans himself up, they emerge from their hiding place looking like themselves again, but instead of returning to town with their tails between their legs or even getting back in their car and driving away, they just start walking, eager to put as much distance between themselves and civilization as they can.

The back half of the film is where the Gerry comparisons are most apt, as it mostly consists of Thomas and Guy-Manuel encountering more and more desolate stretches of desert, alternately accompanied by the sound of crickets and their own footsteps, pieces of classical music, and psychedelic folk singer Linda Perhacs’s “If You Were My Man.” The despair that overcame Thomas in the restroom returns with a vengeance, though, and twice he lags behind Guy-Manuel, silently indicating the second time that he wants his partner to activate his self-destruct button. (When Thomas explodes—three times in succession, naturally—it’s in slow-motion, recalling the climax of Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point.)

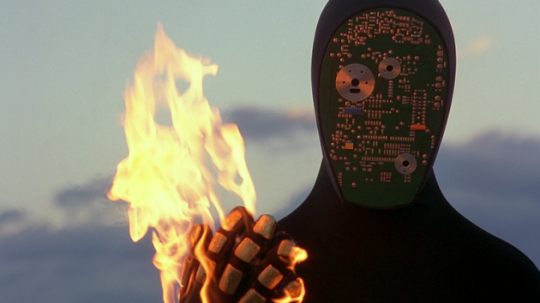

Literally picking up the pieces of their partnership, Guy-Manuel soldiers on alone, even trudging toward a Malickian sunset at one point, but going solo soon loses its appeal and he too decides to end it all, although self-destructing isn’t on the table since he can’t reach his own button. Instead, he resourcefully smashes his helmet and uses a piece of the gold visor to focus the dying rays of the sun and set his own hand on fire. This is followed by what is perhaps the most lyrical shot in the whole film—and it has plenty of competition, since Bangalter is no dilettante—as Guy-Manuel strides from one end of the frame to the other through pitch blackness, completely engulfed in flames, all perfectly timed to Jackson C. Frank’s yearning folk song “Dialogue.” With its repeated refrain “I want to be alone” and lyric about “Changes that were not meant to be,” this sequence conveys more in three minutes than a whole monologue could in the same span of time.

As despairing as the ending of Electroma seems on the face of it, the story doesn’t end there, since it didn’t take long for Daft Punk to rise phoenix-like from the ashes, announcing to the world that they were “Alive” with their ambitious 2006/2007 tour. Preserved for posterity on Alive 2007, its set list found Bangalter and de Homem-Christo breaking down three albums’ worth of songs—hit singles and deep cuts alike—into their component parts and recombining them to exhilarating effect. The intro to lead-off track “Robot Rock” even saw them playfully acknowledging and resolving the dichotomy between their human and robot sides, something their fictional selves weren’t able to manage.

For an encore, Daft Punk returned to the world of film with 2010’s Tron: Legacy, a too-late-arriving sequel mostly redeemed by the band’s soaring score, as well as their too-brief cameo as club DJs on The Grid. That was just a warm-up, though, for 2013’s Random Access Memories, the comeback album to beat all comeback albums. If the underlying message of Electroma (and Human After All) is that the problems of two robots don’t amount to a hill of beans in this crazy world, Random Access Memories proves that two robots who hire a small army of collaborators to put human faces on their musical endeavors can lay claim to all the Grammy Awards they want. It may not have been possible, though, if they hadn’t given themselves the freedom to make something inherently uncommercial first. That’s the legacy of Daft Punk’s Electroma, a film you don’t have to be a robot to love, but it doesn’t hurt.