The Columbine Movie in the Age of Mass Shootingsby Scott Tobias

By Yasmina Tawil

“You know there’s others like us out there.” —Eric, Elephant

On April 20th, 1999, Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold executed a massacre at Columbine High School in Colorado, killing 12 of their fellow students, a teacher, and finally themselves, while wounding about two dozen more. Much would be reported in the aftermath about their motives and other particulars—precious little of it true, according to Dave Cullen’s definitive accounting, Columbine, published a decade later. But the incident was one of those where-were-you-then moments, a horror that unfolded on television and forever colored our thinking on school safety, gun violence, bullying, and a catch-all of possible toxins within the culture, from first-person shooting games to Marilyn Manson records. According to their journals, Harris and Klebold intended mass murder on the scale of the Oklahoma City bombing, and while they failed in that respect, the event nonetheless put an exclamation mark on a decade—and a century, and a millennia—of violence.

Four years later, when Gus Van Sant’s Elephant, a thinly disguised meditation on Columbine, picked up the Palme D’Or and Best Director at Cannes, critics were fiercely divided over the question of representation. Was it even appropriate to make a Columbine movie at all? And was Van Sant successful in adding some perspective to the incident without succumbing to artsploitation or immortalizing the falsehoods that flourished in the aftermath? Writing for the Boston Globe at the time, Wesley Morris, one of the film’s most fervent champions, summed up the controversy thusly:

The film is either a tightlipped essay on the Columbine massacre or a sub-pornographic piece of exploitationist hooey. It’s either a pretentious art director showing off what he can do or the grisliest John Hughes movie ever. The brilliance of Van Sant’s movie is that it’s all of those things.

At the time, there was a too-soon-ness to Elephant that seemed to fuel the criticism against it, like Van Sant had answered one obscenity with an obscenity of another kind. But what does it look like in 2016, when school shootings have become so commonplace that only a handful of the worst ones make the news cycle? Everyone remembers Virginia Tech in 2007 (32 killed), Sandy Hook Elementary School in 2012 (28 killed, 20 aged six or seven), and Umpqua Community College in 2015 (10 killed), not to mention the recent horrors at a movie theater in Aurora, Colorado, a black church in Charleston, and regional center in San Bernadino, California. And yet, can we even remember the names of the perpetrators? It’s like a cancer that’s metastasized across the entire country: The sickness is so widespread now that any one case cannot be examined in isolation for too long. The days when pundits could safely bloviate about violent video games on cable TV now seem positively quaint.

Time often changes our perception of art. Items inevitably shift during flight. But it would seem like the Columbine movie would stand to be affected more than most, because our perspective on mass shootings has evolved so much over the past decade and change. In 2003, Elephant and Ben Coccio’s less-heralded Zero Day attempted to come to terms with a tragedy that many weren’t ready to see referenced or recreated. But no claim of “too soon” can be made in 2016, and it seems possible, too, that Columbine itself doesn’t cast the darkest shadow over the culture anymore. There are too many rivals now, perhaps, for us to get hung up on the moral rightness of Van Sant or Coccio’s artistic choices. So what does the Columbine movie look like now?

In the case of Elephant, it’s remarkable how much the old arguments that came up at the time still apply. If anything, the film looks worse now than it did in 2003, because so many allusions to the killers’ profile—as victims of bullying, as consumers of Nazi propaganda and violent video games, as homosexuals—are not borne out by the facts. Then again, the savvy brilliance of Elephant is that you can’t pin it down to anything so specific to Columbine, because it’s not tied directly to it, just as Van Sant’s 2005 film Last Days could and could not be tied to the particulars of Kurt Cobain’s suicide. The film is abstract enough that we can consider it as a work of art one stop removed from the event, and appreciate it as much in the context of Van Sant’s hypnotic “Death Trilogy” (where it was sandwiched between Gerry and Last Days) as an attempt to engage in a hot-button topic.

With the late Harris Savides’ camera drifting through the halls like a ghost, Elephant is best appreciated as a reverie for the victims, who are each allotted some time before the horrors of the day bear down upon them. Van Sant is credited with the script, but these early scenes were improvised with his young cast and the banality of the dialogue is a deliberate strategy. These kids cannot know what’s going to happen to them, and Van Sant resists the urge to add some special significance to an ordinary morning, at least in the things they say and do. (Two notable exceptions: Eli, whose interest in photography gives him more weight, and John, the one subject who escapes the shootings and takes responsibility for his alcoholic father.) They’re given names, but they don’t exist as “characters” so much as broad types (jocks, art kids, bulimic gossips, a nerd, etc.), because there’s no purpose in whipping up mini-dramas around their part of the couple hours before lunchtime.

In Van Sant’s grand design, all the players in Elephant are roped into the same eerie, transcendent space—the film is less like watching a docudrama than some hypnotic memorial service. Though the last half-hour is punctuated by violence, the overall mood of Elephant is surprisingly gentle; as I wrote in a capsule review at the time, “the film does the important service of stealing Columbine back from pundits and politicians on both ends of the ideological spectrum, all of whom seized upon the event so opportunistically.” It was—and still remains—an opportunity to escape the noise of the aftermath and consider the day from a more reflective, almost meditative, vantage point. The film’s worst critics may decry it as an empty, irresponsible art object, but it could never be accused of being the Columbine movie anyone expected.

Despite the amplification of school shootings and mass murder in the 21st century, Elephant has lost none of its power to seduce and repulse—partly due to the boldness of Van Sant’s aesthetic choices, partly to the fact that memories of Columbine cannot be shaken. Earlier this year, Dylan Klebold’s mother Sue released A Mother’s Reckoning, a memoir that’s been generally well-received, but while time has allowed such a book to be published without public backlash, it nonetheless touches a still-raw nerve. Columbine is the original sin that paved the way for Virginia Tech and Newtown, and so we keep circling back to it, much like Van Sant keeps circling back to the same moment in time in Elephant, right before disaster is about to strike. We’re caught in a feedback loop, doomed to repeat the same horrors.

Van Sant’s facile efforts to access the killers’ motives and psychology are the worst part of Elephant—with this and his Psycho remake, shower scenes are plainly not a strength—but Zero Day makes them the focus. To say that Coccio’s documentary-like treatment of two Columbine-like killers didn’t get much traction in the culture would be an understatement: According to Box Office Mojo, it made just $8,466 theatrically, a micro-return on a $20,000 micro-budget. But it deserves to be remembered as a substantive consideration of what kids like Harris and Klebold might have been thinking—and one that dodges some potential minefields of its own.

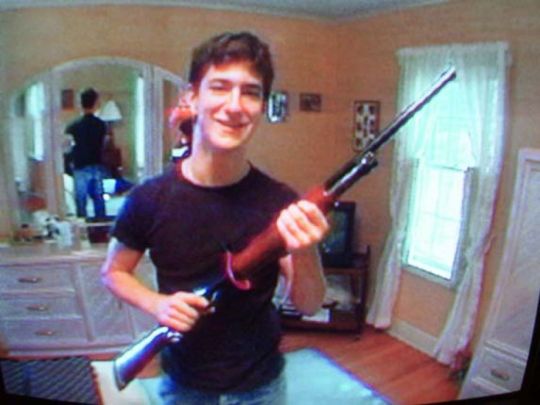

The found-footage approach—fresher at the time than it may seem now—has the perpetrators of a school shooting, Andre (Andre Keuck) and Cal (Cal Robertson), recording a video diary in the lead-up to the event. There’s some egotism behind the diary: They want to be remembered as clever and meticulous in their planning, rather than a couple of dumb yokels who are acting out of blind rage. There are some practical reasons, too: They’re stealing their guns and ammunition from Andre’s father and cousin, and they need the authorities to know that their relatives had no knowledge of the crime they intend to commit. The overall purpose is to be in control of their own story, to keep it from getting hijacked by people who might have a different spin on it.

In other words, Zero Day is a reaction to the reaction, Coccio’s attempt to criticize those who speculated endlessly about the whys of Columbine. “There are no reasons,” says Andre, the undisputed leader of this “Army of Two,” in the final recording before the event. And with that, Coccio offers his thesis statement. In its obsession over the planning of this “secret mission,” Zero Day is a film about the banality of evil, with Andre and Cal often seeming more like organizers than sadists. But Coccio isn’t interested in speculating too far beyond what Andre and Cal allow us to see: Andre’s relatives seem perfectly decent (and responsible gun owners, in that they keep their arms under lock-and-key) and the boys don’t have a specific target for their homicidal aggression. They hate high school and they think other kids are stupid. That’s about it.

Elephant and Zero Day have almost nothing in common—the former a glancing aesthetic experiment, the latter a blunt treatment of killers on the make—but they both implicitly urge viewers not to expect answers to the big questions surrounding Columbine. These are unsettling films that assert the value of remaining unsettled. We can’t know precisely why Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold killed their fellow students, what toxic combination of cultural and personal disturbances led them to embrace the unthinkable. We don’t get closure on Columbine and only bad art would endeavor to provide it. It’s the same open wound now as it was when these films were released 13 years ago. The only difference today is that it’s one wound among many.