Getting the Gold Watch: Famous Actors Who Went Into Retirement and the Films that Drove Them There by Rob Thomas

By Yasmina Tawil

Whether a ditchdigger, an astronaut or a film critic, we’ve all had that moment: Take this job and shove it. We just can’t imagine ourselves getting up and going through another day of work. The thought of hanging it up, accepting the gold watch and retiring early is just too tempting.

In cinema, however, it’s pretty rare to see an actor or actress actually walk away from the business. Plenty are shown the door involuntarily, as has-beens and never-wases find Hollywood to be an unforgiving place. But to walk away from film acting while you’re still a bankable star? Pretty rare.

But some movie stars have hung up their spurs before their time and never (okay, almost never) looked back. In looking over this list of films, we see two gender trends, neither of them very appealing. There are some beloved older actors who walked away from Hollywood, grown cranky at the changing industry. And we see some younger but still vital actresses who found themselves having to choose between a flagging career and starting a family.

Here’s a look at some of cinema’s most famous retirees, along with the final films that may have pushed them into early retirement.

No list of cranky ex-actors would be complete without Gene Hackman, the character actor’s character actor. Hackman seemed like an irascible old coot even when he was playing Popeye Doyle in the original French Connection at the tender age of 41.

So it’s no surprise Hackman’s battered, take-no-bullshit give-no-bullshit authenticity became even more appealing as he aged. In the year 2000 alone, he memorably played the eccentric family patriarch of Wes Anderson’s The Royal Tenenbaums and an aging thief in David Mamet’s Heist.

Then came 2004, and Welcome to Mooseport. Hackman played the former President of the United States, who runs for mayor of a small town and ends up embroiled in a political race with a local (Ray Romano) that turns unexpectedly nasty. It’s not a good film, and an enjoyably cranky Hackman performance gets lost in sitcom subplots.

And just like that, at the age of 74, Hackman was done. He now spends his time writing historical novels, and told a GQ interviewer in 2011 that he’d only do another movie if they could shoot it in his house, only had a crew of one or two people, and didn’t break anything while they were there. Somebody should take him up on it.

Sean Connery probably wouldn’t even go that far. The first James Bond walked away over a decade ago from a long and successful career in Hollywood and seems to have never looked back. He left after a flurry of roles that were likely lucrative but not well-received, including The Avengers and First Knight. He was actually quite good in one attempt at serious Oscar-bait acting, Gus Van Sant’s Finding Forrester, but it was an outlier.

The straw that broke the camel’s back was The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen in 2003, a bloated action-fantasy franchise with only the flimsiest connection to the Alan Moore comic book series. Connery’s grandfatherly charm was lost in a mess of bad CGI effects and incomprehensible action. As Allan Quartermain, Connery looks positively pissed off at certain points during the movie.

Not long after the film tanked at the box office, he announced through a spokesman that he would never do another film because he was “fed up with the idiots… the ever-widening gap between people who know how to make movies and the people who green-light the movies.“ Connery has done a couple of voice acting roles, most notably returning to the role of 007 for a From Russia With Love video game, but that’s it.

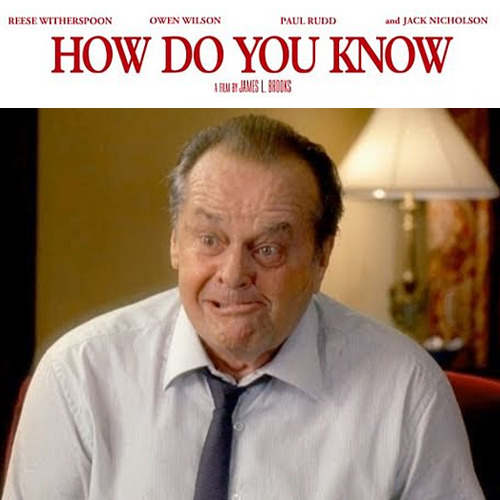

Carrying more of a question mark next to his name is Jack Nicholson, who has not announced his retirement, but hasn’t made a movie since 2010’s How Do You Know and has no projects in the works. Like Connery and Hackman, he’s expressed distaste with the current state of Hollywood moviemaking.

His part in How Do You Know (itself coming off a three-year break for Nicholson) seems like a favor to his friend, writer-director James L. Brooks, with whom he had worked on Terms of Endearment and As Good As It Gets. Here, Nicholson plays the heavy, a bullying and corrupt financial tycoon who is the father of Paul Rudd’s nice-guy character. One gets the sense that it wasn’t this role that has kept Nicholson away from Hollywood ever since, but it didn’t help.

So, three actors, all able to walk away into retirement while still highly employable in movies, if they weren’t always getting the best roles. It speaks to the power imbalance between men and women in Hollywood that they were able to amass such long, illustrious careers and then leave on their own terms, simply because they tired of the work.

For actresses, it’s often a different story. The examples of well-known actresses going into retirement often feature women in their 30s and 40s, not their 70s, facing both Hollywood’s notorious antipathy towards older actresses and the demands of family.