The Two Werner Herzogsby John Redding & B. A. Hunt

By Yasmina Tawil

Raffi Asdourian/Flickr (CC BY 2.0) | Pepe courtesy Matt Furie/mattfurie.com | Remix by Jason Reed

Werner Herzog, that hypnotic German filmmaker who once tried to murder his leading man, who taunted death atop a soon-to-erupt volcano, and who looking upon the screeching Amazon mused that he saw only pain and misery in the jungle, was on a press tour. He sat beside his producer Jim McNiel, both bundled up in the Park City cold, and listened politely as the Los Angeles Times Steve Zeitchik asked about his new film.

It was 2016 at the Sundance Film Festival, and Herzogs latest documentary, Lo and Behold, Reveries of the Connected World made its debut in the festivals Doc Premieres section. The film saw Herzog turning his inimitable lens to the ramifications of modern technology, and initial reviews (at least those counted by Rotten Tomatoes) were uniformly positive. One critic for The Young Folks said Herzog took the same adventurous spirit that made him drag a cruise ship across a Peruvian jungle in Fitzcarraldo and put it toward exploring the labyrinth of the internets history. Many more remarked on the films wondrous, sobering, and truly Herzogian revelations about mans place in the midst of an unprecedented technological revolution.

Zeitchik asked Herzog directly, why make a film about the internet?

We should know in which world we are living, he responded. As thinking people, we should try to scrutinize our environment and know in which world we live.

Well, this is the world in which we live:

Lo and Behold is a commercial.

It was produced by Massachusetts-based network management company NetScout, in conjunction with New York ad agency Pereira & ODell; borne not from Herzogs own passions, but from those of a marketing team seeking to promote a corporation in the midst of a massive rebranding effort. Marketers might bristle at the exact term, commercial, preferring instead the term branded content, one tool in an industry-wise trend towards nearly-invisible advertising meant to implant a positive perception of a companys identity.

After Lo and Behold played Sundance, several reviewers mentioned NetScout had provided the funding, but not one writer took that detail further. Critics focused on the films structure and Herzogs larger-than-life persona, and no one stopped to ask just who NetScout was, and why they had made this film. Perhaps it was the promise of Herzogs integrity and character he had fought and earned for himself throughout his career as cinemas wild man that kept anyone from asking questions. In what world could the man, who has braved deserts, the antarctic, and war zones in the tireless pursuit of filmmaking, sell out?

Branding Cinema

Historically when one spoke of the cross section of advertising and filmmaking, they spoke of product placement – James Bond drinking Heineken in Skyfall, Tom Cruise wearing Aviators in Top Gun, or E.T.s beloved Reeses Pieces. But something different happens when advertising agencies realize that they dont just have to tag-along on a film, but can influence its very structure.

In the late 1990s, while scripting Cast Away, Tom Hanks and William Broyles Jr. approached FedEx with an unusual offer. They said let us use your companys likeness, and in exchange you can help produce the film. Hanks and Broyles problem was that the inciting event of Cast Away was the gruesomely detailed crash of a plane branded with FedExs markings.

Company representatives recalled to The Chicago Tribune:

[FedEx spokeswoman Sandra] Munoz said FedEx decided that the script highlighting the company’s humble origins, its global reach and can-do spirit outweighed the aircraft disaster. FedEx provided filming locations at its package sorting hubs in Memphis, Los Angeles and Moscow, as well as airplanes, trucks, uniforms and logistical support. A team of FedEx marketers oversaw production through more than two years of filming.

This new relationship in which a third partys marketing team oversaw the production of a high-budget film, foretold a major change in the way companies and cinema interact.

A managing director for FedEx said, “As we stepped back and looked at it, we thought, It’s not product placement, we’re a character in this movie. […] It’s not just a product on the screen. It transcends product placement.”

In 2001, a year after Cast Away, BMW pioneered their cinematic ad series The Hire. The premise was simple: Clive Owen posed through a series of stylish, high-production value action shorts. The Hire played at Cannes and was so successful that – in what must be some kind of a first – the Jason Statham hit The Transporter was based on the ads. The genius of The Hire is that they are not films about BMW, but films in which the style and power of the automobile act as the architectural underlay for a compelling narrative.

This is branded content. It is not an attempt to insert a brand into a work of art, but to insert a work of art into the brand. As Naomi Klein once described it: the goal [of a corporation] is no longer association, but merger with the culture.

Branded content is a graffiti artist covertly painting original work for a video game company, or a vodka brand working with a music festival to promote gender equality. At its best, it is The Lego Movie, in which the sensory experience of playing with LEGO blocks is lovingly evoked to tell a story. That films careful digital animation stands as not just some of the most impeccably textural filmmaking ever attempted, but as a cruise missile of nostalgia aimed at the viewer. The Lego Movie nearly doubled the worth of its parent corporation.

Such a thing has never really existed in film before, but it is very similar to the early years of television, when companies like US Steel, Alcoa, or Kraft would pick up the tab for a show in exchange for the prestige of having their name on it. A great deal of powerful programs were produced in this era of television, but none free from compromises. Rod Serling was just one of many talented writers who found themselves increasingly stymied by his sponsors patter of seemly changes. In the introduction to the paperback edition of his great teleplay Patterns, Serling cautioned us about mixing corporations and art: I think it is a basic truth that no dramatic art form should be dictated and controlled by men whose training, interest and instincts are cut of entirely different cloth. The fact remains that these gentlemen sell consumer goods, not an art form.

Censorship eventually drove Serling from writing about contemporary society to The Twilight Zone, where he could explore his stories of intolerance and bigotry in a politically-neutral fantasia.

A NetScout Production

Founded in 1984, NetScout specializes in network systems, producing both hardware and software. It was an early developer of packet sniffers, the technology that logs data being transferred over networks. Today, according to its own online bio, NetScout has a heavy focus on cybersecurity, anti-DDoS and Advanced Threat Solutions tech. It also provides web service performance platforms, cloud management, and packet brokers, among many other interconnected divisions.

All this to say, the company operates behind the scenes. It is not purchasing Super Bowl ad time to become a household name, rather its financial investments lie in the sustained prominence and upkeep of the internets infrastructure.

The seed of Lo and Behold formed in 2015, when NetScout was in the midst of a massive company-wide rebrand led by its then-CMO Jim McNiel, who would later participate next to Herzog in the films publicity tour. The company had spent the previous year making major corporate acquisitions, including the communications sector of Danaher Corporation, Arbor Networks, Fluke Networks, Tektronix Communications, and VSS Monitoring. The shopping spree consolidated their share of the communications market and helped the company more than double its revenue to the $1.3 billion it generates today. But NetScout remained a largely unheard of entity outside of the inner circle of the network management industry it had helped pioneer in the 1980s. The company needed a way to boost its status and reach new clients.

And so, Lo and Behold was born in the walls of Pereira & ODells New York office, where the agency has serviced clients such as Intel, Fifth Third Bank, and Procter & Gamble.

It was Pereira & ODells executive creative director Dave Arnold who approached McNiel with a fresh, but risky idea. They would make a feature length documentary celebrating the creation of the internet and the boundless potential of its future. It would engage consumers with a focus on the importance of the technological innovations being made today, and toast the creators and engineers who contract with NetScout for their cybersecurity and hardware needs. The kicker: It would be directed by Werner Herzog.

In a 2016 AdWeek reflection on the film, McNiel wrote that Herzog initially balked at the idea, telling NetScout: No! I do not do commercials.

But McNiel managed to convince Herzog the film was not a commercial, but a serious documentary that would explore the world-changing and potentially apocalyptic ramifications of the internet.

Speaking to McNiel this month, he told us there was no second choice for a director. If Herzog couldnt be won over, the entire project would be scrapped. Why?

Hes an icon, McNiel said. And hes a meme!

Herzog the Meme

Popular arthouse directors have long been a favorite target for ad firms. This past year, Herzogs friend and collaborator Errol Morris directed a series of 56 commercials for Wealthsimple, in which celebrities from all walks, including himself, tell anecdotes about handling their own finances. Wes Anderson has made ads for American Express, Darren Aronofsky has been recruited by Yves Saint Laurent, and Ridley Scott has made advertising history time again with his Hovis, Chanel, and Apple ads.

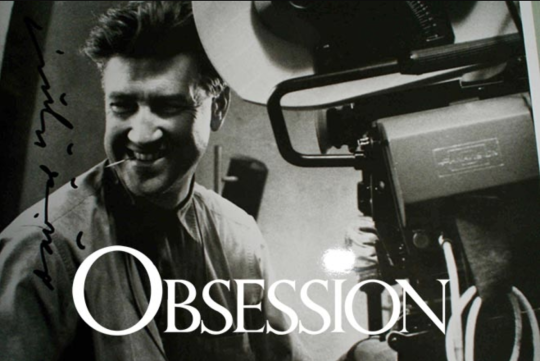

Many renowned directors from Scott to David Fincher to George Romero got their start making commercials. In Japan, Nobuhiko Obayashi was so good at TV spots he was given free reign by Toho to make his psychedelic freakout cult classic House. Even David Lynch, one of the staunchest opponents of product placement in cinema, has made commercials for Playstation, Gucci, and Clearblue Pregnancy Test. When asked during a Q&A if he finds this hypocritical, he answered bluntly: I do sometimes [direct] commercials to make money.

For Lynch, if the ads dont bleed into the art then there is no reason for purists to hold directors advertising works against them; after all Inland Empire probably didnt pay very many bills. Spike Lee has even opened up his own ad agency, and often blurs the line between his core filmography and his ad work, licensing to Nike and performing as his Mars Blackmon character from Shes Gotta Have It, retroactively making his feature debut something akin to after-the-fact branded content.

But Herzog was different. He came from the roiling, unfettered New German Cinema of Syberberg and Fassbinder, where they ranted and bled and snorted endless coke for their art. And even among that crowd, he was different. He came from the fringes, growing up in the mountains of Bavaria and making his first films with a camera he stole from a local university. In the 1970s and 80s, while his contemporaries in the movement like Volker Schlndorff and Wim Wenders went mainstream, he kept his distance. His adventures in storytelling have taken him to every continent on the planet, and he has further cemented his legend with tales of being arrested, threatened at gunpoint, forging documents, and picking locks to forbidden zones all in the pursuit of cinema. Alone, the troubled making of Fitzcarraldo has probably done more than anything else to create the idea of Werner Herzog in the mind of western audiences, that of a madman mystic lost in the jungle chasing truth and art while eschewing formulaic Hollywood methods of filmmaking. His explicit anti-commercialism has made him appear incorruptible to his fans, who still at every chance possible put on impersonations of his signature Black Forest accent.