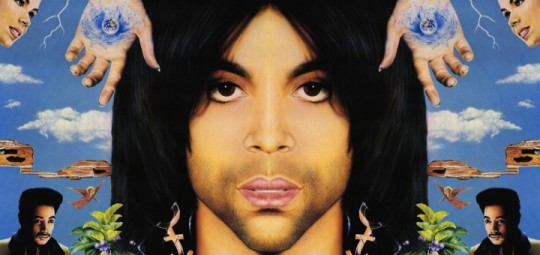

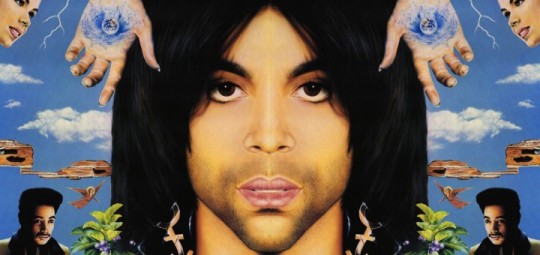

The Unlikely Autobiography of Princes Under the Cherry Moon and Graffiti Bridgeby Jake Cole

By Yasmina Tawil

Princes cinematic legacy effectively starts and stops with Purple Rain, the 1984 smash that cast the artist in a Star Is Born narrative. In the face of the overwhelming apocrypha surrounding the Prince, the film also doubled as mythic origin story by offering a plausible autobiography. Yet despite the enduring entertainment value of the film, it arguably loses something of Princes essence in smoothing out his kinks. Im not a woman/Im not a man/I am something that youll never understand, he sings on I Would Die 4 U, but this Prince is, apart from his aloof demeanor and strange outfits, entirely legible.

To get a cinematic sense of the true Prince, in all his baffling, maddening contradiction, one must turn to his own directorial efforts: 1986s Under the Cherry Moon and 1990s Graffiti Bridge. Released to widespread derision, the films today enjoy trashy reputations that they come by honestly. Nonetheless, each provides a glimpse into the unfettered creative mind of Prince as it struggles to grasp a format foreign to him. The results are undeniably baffling and scattered, but in their contradictions lie an unpolished, unprotected view of Princes personality, artistic worldview, and his well-cloaked self-awareness.

None of this is readily visible on the surface of either film, both of which center their plots on how much Princes characters get laid. In Under the Cherry Moon, he plays Christopher Tracy, a gigolo who, along with his brother, Tricky (Jerome Benton), beds and bilks rich women across the French Riviera. Eventually, he targets loaded heiress Mary Sharon (Kristin Scott Thomas), only to fall in love. Graffiti Bridge takes this split between love and sex even further: In this loose Purple Rain sequel, the Kid (Prince) actively vies with The Times Morris (Morris Day) for the affections of Aura (Ingrid Chavez). This is just a replay of the two figures war for Apollonias hand in Purple Rain, but the twist here is that the Madonna/whore complex that frequently informs Princes view of romance is literalized by Auras ethereal nature. In effect, both the Kid and Morris spend the entire movie attempting to screw an angel.

Princes libidinous forays bring out the rakish troublemaker in him, and the wry sense of irony he displayed in Purple Rain blossoms into a peevish sense of humor. Christopher Tracy delights in messing with Mary, responding to her ability to see through his empty charms by simply doubling down on them. Surrounded by stuck-up elites, Christopher is unabashedly common, and Prince emphasizes his inappropriate outbursts and leers to shake Mary out of her aloofness. In Graffiti Bridge, the Kid is back to his arch ways, but the film itself bursts with a free-spirited comedy. Cartoon sound effects, exaggerated camera movements, and the catty chemistry between Prince and Morris all contribute to a goofiness that shows the artist cutting loose from his solemn, stern image.

The seemingly random stylistic clashes of both films likewise reveal the artist from a new angle. Cherry Moons velvety, black-and-white cinematography (courtesy of Rainer Werner Fassbinder/Martin Scorsese mainstay Michael Ballhaus) provides a grounding element for the manic intensity of the films tone, but the professionalism of the images matches a curious aspect of the movie. Released at the peak of Princes working relationship with Warner Bros, the film looks like a rapid sprint through much of that companys studio history. The smoky nightclubs where Christopher searches for new marks vaguely recalls the setting of Casablanca; Prince and Jeromes teasing interplay updates Abbott and Costello; and the antic, raunchy, gold-digger comedy harks back to the Pre-Code era.

For its part, Graffiti Bridge pulls from a long history of backlot musicals, replacing the semi-realism of Purple Rains Minneapolis setting for a highly chromatic, hyperreal image of a city that appears to consist of nothing but nightclubs. But if the art direction of the previous film offered a playground for Princes melodramatic comedy, the set design of this rotting pleasure city illustrates a societal moral failure that contrasts with the artists spiritual enlightenment, which is cued by the Kids wardrobe as much as his speech. Dressed in flowing tunics and sporting long, straightened locks and a beard that looks drawn in mascara instead of grown, the Kid resembles an icon of Jesus as painted by a particularly thirsty worshipper. Prince had never shied away from airing his religious beliefs, but here he transforms the Kid from an aspiring rock star to someone who would rather spread that spiritual noise, as Morris terms it, than get a platinum record.