The Wondrous, Sensuous World of Astralvision by Charles Bramesco

By Yasmina Tawil

You don’t find it; it finds you, most likely in the dead of night.

You can’t sleep, you may or may not be on drugs (you don’t have to be, though it’d be a lot cooler, as they say, if you were), and you’re clicking around the weirder back channels of YouTube again. You pinball from ‘80s-era NASA test footage to “36 NEW SHOWS FROM THE HELLISH MID-SEASON TV OF 1979” to the deep catalog of VHS oddities discovered and uploaded by a dedicated corps of obsolescence fetishists. It’s here, among the creepy camcorder detritus and lost video-dating profiles, that “Electric Light Voyage” has been waiting for you.

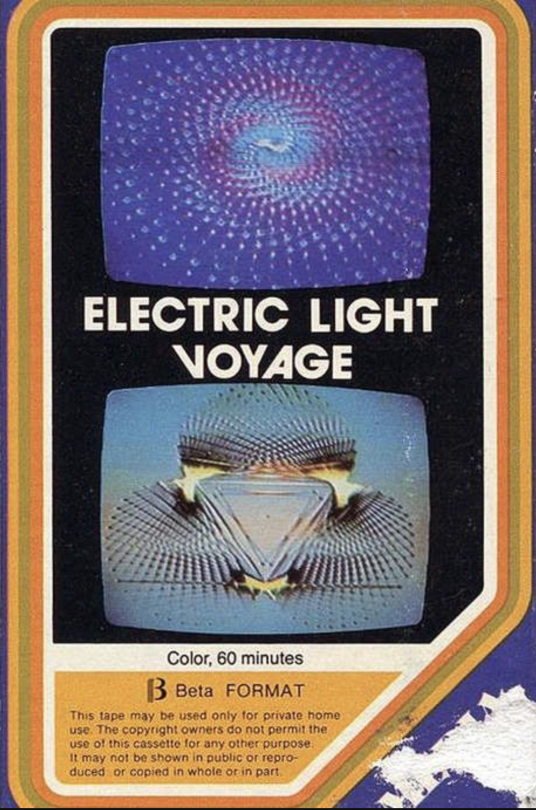

Independent video distributor Media Home Entertainment Inc. released a tape by that title in 1979, re-christened as such by the label in a likely effort to piggyback on some of the then-ubiquitous Electric Light Orchestra’s popularity. The video nevertheless begins with the original introductory card that dubs the 60-minute compilation “Ascent 1,” after flashing the retro-sleek logo of Astralvision Communications, Inc. The gap between the titles chosen by the distributor and the production house—one flashy and fun, the other chilly and practical—speaks to the dual identities of this unusual, singular work. “Electric Light Voyage” sounds like an N64 game, while “Ascent 1” nods to the project’s roots in science and experimental art. This wondrous, strange nostalgia object effectively splits the difference between those two worlds, a treat for both avant-garde aficionados and people looking for something to stare at.

The conflicting titles make it all the more difficult to ascertain information about this curio, little-seen and widely forgotten as it is. The short-lived Astralvision Communications Inc. seems to have been established for the sole purpose of assembling this collection of shorts; the Astralvision trademark lapsed after it failed to renew in the ‘80s. The end credits clarify this as a joint effort from a loose collective of video artists in the general orbit of University of Illinois at Chicago during the ‘70s. Astralvision acted as a sort of professional extension of the Electronic Visualization Laboratory—the National Lampoon to their Harvard Lampoon, if you please—an on-campus program that incubated the earliest exchanges between art and computer engineering.

The ELV had been founded by two graduates-turned-researchers, Dan Sandin and Tom DeFanti, who would each go on to fabulous success in the field. DeFanti created GRASS, the programming language that gave us Star Wars’ Death Star sequence, and Sandin invented the Sandin Image Processor, a device that “drew” visual patterns the way a Moog “plays” sound. A young woman named Barbara Sykes learned of their Electronic Visualization Events—brain-expanding live performances of video and audio synthesizing in real time—and started to attend during her time at the university. She would become their most brilliant student and valued collaborator, credited here with “Video Synthesis” on multiple segments. The trio contributed the lion’s share of the work that ultimately made up “Electric Light Voyage”/“Ascent 1,” and in packaging their esoterica for public exhibition, they opened a direct portal from their technological be-ins and the museum galleries they later occupied to after-dark living rooms across America.

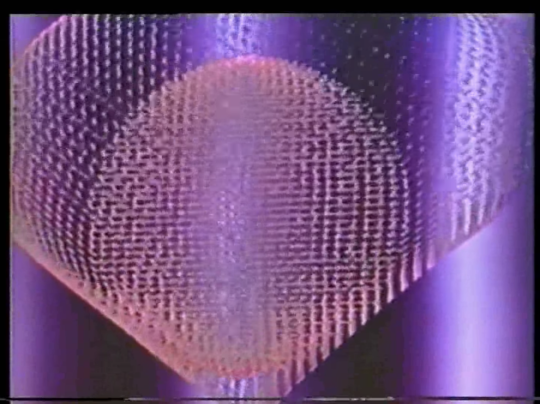

So, uh, what is it? Sykes, Sandin, DeFanti, and their cohort may not have been the very first video artists, and they were far from the first experimental filmmakers, but they did pioneer a new form borrowing liberally from both of those traditions. The Sandin Image Processor, the implement of choice on most of the included shorts, brought abstract expressionism into the virtual plane. Twiddling the right knob or turning the right dial on a physical panel sends a signal through a number of filters that can alter the shape, color, and motion of the feedback pattern. The description on the back of the VHS box offers a somewhat snappier explanation:

This 60-minute electronic fantasy featuring computer animation can control and change your moods of elation and tranquility. To change or enhance your mood, simply play a musical selection that accompanies your present feeling – it’s mesmerizing! The abstract colorized computer animated visuals are artfully paced with their complimentary soundtrack. Images explode with color while soothing with flowing shapes and rhythms. Great for parties or individual contemplation.

In other words, it may not have been a coincidence that DeFanti named his most significant innovation after a slang term for marijuana. A viewer can nearly smell the reek of cannabis wafting out of the psychedelic swirls, begging as they are for the overtaxed descriptor of “trippy.” But there’s more to it than, say, the iTunes Visualizer. Though that program serves a similar function, creating a pleasing computerized light show for anyone looking to zone out, the methods at use in “Ascent 1” are more sophisticated in their deliberateness. The Visualizer employs a code to generate a randomized series of neon-colored portals that shiver along with the beat of whatever song’s being played; each segment of “Ascent 1” encompasses a carefully plotted journey with timed peaks and valleys. (Oh, so that’s why they call it a trip!)

Functionally speaking, it’s much closer to something like Plantasia, precisely due to its nature as a functional artwork. Synthesizer virtuoso Mort Garson composed that 1976 album for the express purpose of accelerating houseplant growth, and the Astralvision house went about their process with a utilitarian bent as well. They believed that visual and aural stimuli could have an immediate, visceral effect on a person’s physical and mental state. Drug users just happen to be particularly susceptible to a phenomenon the creators wanted to share with everyone, in which feelings of anxiety and unease can be dissolved via sensory triggers. The technique is far from airtight—the highly subjective effects of drug use mean one person’s good vibe could be someone else’s hell-abyss—but it’s affective and effective all the same. Sober or no, fully engaging with the images flushes out everything else and casts a therapeutic spell. The tape hiss makes the rest of the world fall silent.

The ambitious terms of the project’s conception shouldn’t detract from its merit as an artwork for its own sake, however. Each short tests the limits of a medium then in its nascency, somewhere between the first tinkering and complete mastery of such devices as the Image Processor. The engineers conducted wild stylistic experiments playing primal forces against one another: music vs. noise (and within that, organic instruments vs. the synthesizer’s various blips), stillness vs. movement, color vs. shape. Bob Snyder and Michael Sterling’s scores move freely between industrial sound effects, synthetic whalesong, Moog tinkering, and free-form electric piano. Of the many new frontiers charted, most fascinating among them may be the full elimination of editing; images melt into one another, legato light fades and mutating geometric forms taking the place of cuts.

The attempts to induce a sort of artificial synesthesia were not without a textual content, either. Though none of the shorts even comes close to anything that could be charitably called a story, they do occasionally sketch variations on a single theme, not unlike the jazz accompanying some of the segments. Sykes took the lead on the first two segments, “By the Crimson Bands of Cyttorak” and Circle 9 Sunrise,” both compositions originating during the Electronic Visualization Events. Her later work would engage with feminine imagery in a more concrete capacity, focusing on Athena and Amazons and their mythical ilk. Still, look closely and the beginnings of her interest reveal themselves in the curvaceous, vaguely yonic linework. Sandin and DeFanti share credit on “Spiral Ryral,” which contrasts a Warholian silhouette of a humanoid figure with rows of spermatozoa wriggling in the background. Symbolic iconography nudges the wandering brain in this direction or that, and it floats along with the onscreen tide.

Even as they fall under its hypnotic sway, modern audiences cannot help but approach this vintage find from an anthropological remove. Animation ages differently than live-action cinema, and computer animation’s no exception. The Internet’s now full of videos toying with sensation using fractal imagery — there’s an argument to be made that the Astralvision house came up with ASMR decades ahead of schedule — but there’s an engrossing primitivism to “Ascent 1” that can’t be found elsewhere. It’s in league with Carl Theodor Dreyer’s Vampyr, or Pete Drake’s trial runs with the talkbox: a vision of the future now rooted in the past. “Ascent 1” suggests a daring vision of an art form’s possible future that’s all the most intriguing for only getting it right a little. Sykes, DeFanti, and Sandin’s compositions presage the advent of the screensaver, and yet they unmistakably belong to the past of laser Floyd shows and industry-standard cassette use. It’s in the intangible elements: the crackly edges of the robot hymns on the soundtrack, the soft-definition fuzziness that recalls both the filmstrip’s warm grain and the antiseptic sheen of videotape. Not quite analog and not quite digital, crude and wondrous, “Ascent 1” is a window to a time when computer technology was still unsettled territory. In the melodies and murals of machines, we hear the pre-verbal burblings of a medium.