The Hollywood from Another World: Bowfinger, Get Shorty, and Living in the Movies by Daniel Carlson

By Yasmina Tawil

The movies have always been in love with themselves. For all their heroes and villains, lost loves and epic stories, Hollywood’s greatest source of mythology has always been its own history. Almost from the birth of the medium, movies have explored the filmmaking process and satirized their own development, acting out existential investigations that let the viewer in on the joke while keeping them at arm’s length. By taking place inside the machinery of filmmaking, the narratives seem to offer a glimpse of the “real” Hollywood, but the finished product is still, itself, a movie, and its representation of “reality” is always going to be heightened and enhanced to keep the audience entertained. There’s a constant tension at the heart of these films. The more they try to pull back the curtain, the harder it is to see what’s really behind it.

Hollywood got an early start on self-awareness. Hollywood and Souls for Sale, both silents from 1923, as well as 1928’s silent Show People, are comedies set in the nascent world of film production that are stuffed with cameos from stars of the era. More incisively, there’s 1924’s Merton of the Movies, which originated on Broadway and told the story of an aspiring actor with a penchant for overwrought, hammy acting, so much so that a studio casts him in a comedy but tells him he’s filming a drama. Right there, you’ve got the star-making process, the average person’s thirst for fame, and the duplicitous ways that suits conduct business, all played for knowing laughs. Almost a century later, the story hasn’t really changed.

Yet what’s become so fascinating about these kinds of movies is that as film history marched on, it became possible to fold real films into the fictional narratives, and for actors playing characters to reference other actors by their real names. Little winks like that pop up everywhere — Lauren Bacall in How to Marry a Millionaire talking about “that old fella, what’s his name, in The African Queen”; Cary Grant name-checking Ralph Bellamy in His Girl Friday, in which Bellamy also starred — but they take on new meaning when they happen in movies that are themselves about the filmmaking process. Characters making movies talk about real-world pictures that we, the viewers, have seen. It’s a way to bolster the credibility of their fictionalizations, but it also makes for a pleasantly disorienting experience. Instead of pure suspension of disbelief and pretending that, say, Tom Hanks doesn’t exist in Tom Hanks movies, we watch actors invoke their real-life colleagues in ways that blur reality. The films create a world that might be called Alternate-Universe Hollywood: recognizably our own, yet unavoidably foreign. There are plenty of ways to do this, from the absurdity of Tropic Thunder to the existential dread of The Player, but two comedies from the 1990s stand out for their charm and precision: Get Shorty and Bowfinger. Individually they’re great — funny, quick-witted, entertaining — but they’re also prime examples of how to tell an Alternate-Universe Hollywood story that feels as strong twenty years later as it did the day the print was struck.

Get Shorty was released in 1995, five years after the Elmore Leonard novel that inspired it. The story follows loan shark and film buff Chili Palmer (John Travolta) as he pursues a debtor to Los Angeles and decides to become a movie producer. Like most movies about movies, it’s a love song to the idea of Hollywood-as-dream-factory: Chili’s eyes sparkle when he talks about the classics, and he starts to win over his love interest (Rene Russo) at a screening of Touch of Evil. There are even moments that quote 1932’s Cabin in the Cotton. But modern Hollywood is dealt with more vaguely: while established stars who gained fame in the 1970s and 1980s are mentioned, specific films from recent years are only alluded to in a general way. Take Chili’s pontification on whether he could step in front of the camera: “I can see myself in the parts that Robert De Niro plays, or maybe an Al Pacino movie, playing a real hard-on. I couldn’t see myself in a movie where like the three guys get left with a baby, they don’t know how to take care of it, so they act like assholes.” He’s talking, of course, about 1987’s Three Men and a Baby. But that film was only a few years old when Get Shorty was released, and as a result, bringing it up runs the risk of making the film feel dated, tied to the period in a way that’s ironically less likely to happen by name-checking films from decades prior. It’s partly because classic films have had time to let their reputations grow, evolving into a canon everyone can invoke. Newer films, though, don’t have that luxury.

There’s also a reason Chili doesn’t say the film’s title but does describe its plot. It’s an example of what’s known as distancing language, which is when generalities are used to place a subconscious distance between the speaker and the object in the mind of the audience. It pops up about every week in politics: “I did not have sexual relations with that woman” might lack grace, but it still plays better than “I didn’t sleep with Monica.” The phrase “that woman” is a distancing one, and phrases like that manage to simultaneously evoke something specific without actually bringing it all the way into the room. So when Chili all but says “it’s a movie about three men and a baby,” he’s able to call the picture to mind for viewers, but not in such a way that Get Shorty becomes irrevocably linked to it. The film floats along on the surface of its era.

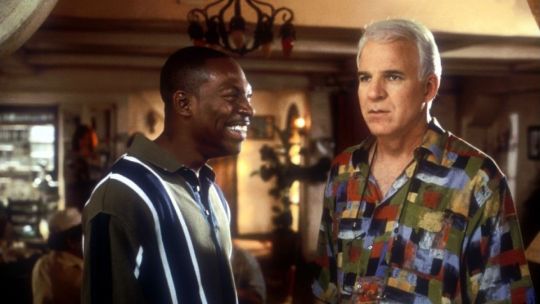

Bowfinger does this, too. Released in 1999, it’s a comedy about a hacky, broke, off-brand director named Bobby Bowfinger (Steve Martin) who decides to make it big by filming a sci-fi action movie starring A-lister Kit Ramsey (Eddie Murphy). His scheme: to shoot the film on hidden cameras and without Kit’s knowledge by having his cast walk up to Kit, deliver their lines, and run away before Kit can do anything. Things get even more complicated when Bowfinger is able to cast Kit’s nerdy brother, Jiff (also Murphy). Where Get Shorty is breezy, Bowfinger is slapstick, but it’s just as committed as the earlier film to the notion of pretending it’s set in the “real” Hollywood. Its references and distancing language show up when Bowfinger tries to make the case that it’s OK to surreptitiously film a star without their knowledge, saying, “Did you know Tom Cruise had no idea he was in that vampire movie till two years later?” Sure, the line works as a gag, and it’s a little smoother than Chili’s dismissal of Three Men and a Baby, but it also does its job by selling its reality instantly — this movie is set in the world we know, the one that saw the release of Interview With the Vampire — before scooting along to the rest of its narrative. It becomes a nice way to color in some of the details, making things just real enough.

The dichotomy between the way each movie talks about older films (specific names and titles) and newer ones (fuzzy references and loose plot summaries) also underscores the way they’ve constructed their own semi-fictional worlds. That is, in each movie, at some point in the past, events diverged from what we think of as “real” and became the reality of the movie. Specific references to the recent past would only call attention to that gap, so they’re usually avoided. This happens a lot in movies and TV that try to seem like they’re partially set in the real world: characters on NBC’s The West Wing, for example, made regular and specific references to American presidents up to Eisenhower, but, aside from an oblique mention of White House tape recorders, no presidents from the latter half of the 20th century were discussed. At some indistinct point in the show’s narrative past, the history stopped being ours and started being theirs. Get Shorty and Bowfinger have to do the same thing because they’re movies about movies, but they also feature actors with connections to other movies. That is: Chili Palmer can talk about Pacino all he wants, but he can’t reference Saturday Night Fever. It would expose the cracks in the wall. They are fictional glimpses of real things, destined to be misleading. They can only present a version of reality, but because it’s all we have, we wind up giving it credence, and the line between what’s real and what we want to be real gets a little blurrier.

Where these movies really get interesting, though, is the types of fictional films they revolve around. In Get Shorty, Chili finds himself doing business with Harry Zimm (Gene Hackman), a man who, like Bobby Bowfinger, is known for a career of B-movies and creature features and is hoping to finally achieve real success and legitimacy by making a quality drama. Yet there’s a naivete, almost a sweetness, about the way each film treats its hack directors and the way it envisions these movies could actually exist in their respective eras. Zimm’s major star, Karen Flores (Rene Russo), is trapped in the kind of schlocky monster movies that started being phased out in the 1960s, and Bowfinger’s movies are aimed straight at the bargain bin. It’s not that these types of movies are unrecognizable. It’s that they’re so old.

The Hollywood of Get Shorty and Bowfinger shows no signs of any evolution in genre pictures past the 1950s. Monsters live in lagoons and stalk young women; aliens come to earth inside raindrops that melt victims’ faces. The film brats of the 1970s get name-checked, but not the summer movie culture they eventually created. Superheroes are nowhere to be seen. In other words, this is a Hollywood where blockbusters as we know them never happened. There are no YA franchises on the horizon waiting to dominate opening weekends, no Batman or Superman, no Star Wars, no sequels. There are, it goes without saying, no #brands. Chili Palmer wants to make a movie with an actor named Martin Weir (Danny DeVito) in part because he’s gained fame for playing Napoleon, not the Penguin. Bobby Bowfinger seems to have woken from a four-decade nap. The Hollywood of these movies is drastically different from our own because, for all their focus on power and fame, they’re ultimately set in a filmmaking world that revolves around movies made by and for adults.

What’s more, they were made and set in an era when film production stories were still mostly inside baseball. The 24/7 casting-and-trailer-pics news cycle had not yet been invented — Ain’t It Cool News was founded the year after Get Shorty came out — and aside from pieces in Premiere or Entertainment Weekly, there was a gap of understanding and access between casual movie fans and the way the sausage was made. The Hollywood of Get Shorty and Bowfinger is hermetically sealed and set apart from the real world and its consequences. There’s never a sense that anything that’s happening will get out or leak, or that tales of battles over who’s going to produce a script will go any farther than the conference room door. As a result, for all their efforts not to sound or look dated, they wind up feeling like period pieces.

That’s really why they work so well, so many years after their release. They didn’t want to be of their era, but they couldn’t help it. No one could’ve foreseen that tidal shift that would happen just a few years later, as superheroes became the biggest ticket in town and movie fandom morphed into coverage of the next hot franchise. These movies exist in a pocket of time right before the Internet changed the consumption and perception of film, and their Hollywood feels somehow smaller, quainter, slower paced. They’re in love with motion pictures as a racket and an art, and they don’t have any illusions about the fickle nature of the entertainment industry or the lengths people will go to in order to get a film made. But they’re also sweet on the whole mess. And they, too, are part of that Hollywood before the rise of caped men and fated tween heroines. If they’d come out later, who knows if they’d have been the same; who knows if they’d have been made at all. That they were feels like a gift in its own way. We have these two bright, small, sharp little comedies that set out to satirize Hollywood but wound up being love letters to a way of life no one realized was about to end. They’re enough to make you remember why you loved movies in the first place.