The Doomed Romantics of An American Werewolf In London and The Fly by Craig J. Clark

By Yasmina Tawil

When John Landis’ An American Werewolf In London was released in 1981 and David Cronenberg’s The Fly followed five years later, what initially grabbed people’s attention were the Academy Award-winning creature effects by Rick Baker (whose work on the former prompted AMPAS to create the Best Makeup category) and Chris Walas (whose other reward for his part in The Fly’s success was the opportunity to direct its less memorable sequel). Charged with updating horror icons of the ’40s and ’50s for savvy moviegoers primed to be dazzled by state-of-the-art special effects, Baker and Walas stepped up to the plate and delivered unforgettable monsters and set-pieces that have earned a permanent place in movie history. Even today, their work continues to impress, evincing a staying power that modern digital effects have a hard time sustaining. But what keeps viewers coming back to these two films time and again are the human love stories than run parallel with the bloody carnage and acid-spewing monster-men.

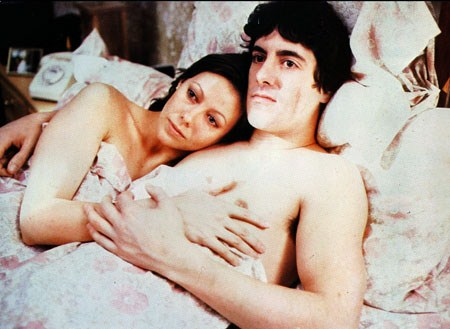

While both films have fantastic premises—namely, that a man bitten by a werewolf will become one himself and a man who teleports himself with a housefly will become a man-sized fly—they’re grounded in the mundane and the every day. Take the London flat of nurse Alex Price (Jenny Agutter) in American Werewolf, which reveals a lot about her that she might otherwise be reluctant—or unable—to say out loud. Having taken a fancy to him, Alex brings home American backpacker (and unwitting werewolf) David Kessler (David Naughton) after he’s discharged from the hospital where she’s been tending to him while he recovered from an animal attack on the Yorkshire moors. Warning him not to expect too much since she’s “just a working girl,” she shows him around her cramped quarters, which art director Leslie Dilley and his crew make look as lived-in as possible without being too cluttered. The living room has plenty of throw pillows, photographs on the mantle, and shelves crammed with books and knickknacks, while the bathroom has little plants in individual pots. The hallway leading to her bedroom even has a single flower in a box mounted on the wall, which David’s zombie friend Jack (Griffin Dunne) playfully smells when he pays them a visit later that night. The very first thing the viewer sees when Alex lets David in, though, is a Casablanca poster hanging on the wall, closely followed by one for Gone With The Wind. And briefly glimpsed in her kitchen is an enlarged photograph of Humphrey Bogart. Even if she’s being truthful when she says she’s “not in the habit of bringing home stray, young American men,” it’s clear she has a thing for American culture (see also: the Disney paraphernalia scattered about) and a romantic streak a mile wide.

Compare that to the spacious loft owned by Seth Brundle (Jeff Goldblum) in The Fly. Wide open, unfinished, and mostly unfurnished, his combined living/workspace—a converted factory he hasn’t put much effort into making cozy and inviting—reflects how thin the partition between the two are for him. The only human touches, in fact, are a fold-out couch, a red leather chair, and the upright piano that production designer Carol Spier and art director Rolf Harvey have installed in it, as well as the cappuccino maker (a Faema, the brand with the eagle on top) Seth uses to lure journalist Veronica Quaife (Geena Davis) back to his lab, along with the promise that he’s working on something that will “change the world as we know it.” Much like Alex, here’s a man who’s not accustomed to bringing attractive members of the opposite sex home, but his desire to impress Veronica with his telepods temporarily overrides his desire to go to bed with her—or maybe he believes the one will lead directly to the other. Either way, it’s telling that she’s out the door not long after he performs his demonstration—on one of her stockings, proving how forward she can be when she wants—while Alex and David are having shower sex within minutes of her showing him around her flat. Then again, their flirtation did have a few days’ head start and neither of them had any illusions about where they were headed.

Since David is a tourist, he has nowhere else to go, but Veronica’s tastefully decorated apartment in The Fly is comparable to Alex’s living space in American Werewolf in terms of its homeyness, though Seth never visits. (Appropriate since their relationship winds up being entirely on his terms.) Instead, the only man who pays a call on her there is Stathis Borans (John Getz), her editor and former lover, who drops in while she’s out to take a shower because, as he says when she catches him, he “felt a bit scummy.” Stathis’ function in the plot is to be the fly in the ointment, as it were, provoking Seth’s jealousy after he and Veronica become involved. In fact, his mistaken belief that she’s still sleeping with Stathis prompts Seth to teleport himself without her—along with the fly that gets into his telepod unnoticed, setting the stage for his monstrous transformation. While David’s agonizing change from man to beast happens in a matter of a minutes, though, Seth’s metamorphosis into Brundlefly is a gradual process shown in stages, mirroring the steady decomposition of David’s friend Jack, who died during the werewolf attack that left David cursed with lycanthropy and who visits him periodically to try to convince him to kill himself. (Tellingly, at the end of each of their transformations, all three are portrayed by puppets, albeit extremely sophisticated ones.)

The amount of time the couples in both films get to spend together before they’re torn apart by circumstances beyond their control reflects how deep their relationships are allowed to get. In American Werewolf, Alex doesn’t meet David until after he’s been bitten, meaning their love is doomed from the very start, but that still leaves them a few days to get to know and care about each other before the change first comes over him. “I find you very attractive and a little bit sad,” she tells him the day she brings him home, not realizing how much sadder she’ll be roughly 48 hours later. In The Fly, Seth’s fusion with a housefly at the genetic level doesn’t occur until after Veronica have been staying with him for some time, placing her in the unenviable position of being able to observe how he changes emotionally as well as physically once he’s taken a dip into “the plasma pool,” as he poetically puts it. It’s his increasingly erratic behavior that drives her away, though, as his insectoid half comes to dominate his personality. In contrast, after taking the lives of half a dozen Londoners in a single night, David goes back to being his usual bubbly self, blissfully unaware of what he does by the light of the full moon until the bloody results of his nocturnal rampage are grotesquely paraded before him in the stalls of a porno theater.

As different as the central couples in American Werewolf and The Fly are, especially in terms of their maturity, there are still some striking similarities between them. Most obvious is the fact that it’s the men who change into monsters while the women are relegated to the role of observer. (In Veronica’s case, that’s her job from the start, since Seth initially invites her into his life simply to document his experiments.) And while it’s strongly implied that the men are sexually inexperienced—potentially virginal, even—Landis and Cronenberg lay their female characters’ sexual histories bare. In fact, while broaching the subject, Alex blurts out how many lovers she’s had, including the number of one-night stands. Notably, David does not respond in kind. As for Seth, he’s so clueless when it comes to matters of the heart that while he’s falling in love with Veronica he has to ask her, point blank, “Is this a romance we’re having?”

That one line speaks to the fundamental difference between the two films and the approaches of their makers. Befitting a film whose writer/director is primarily known for comedy, American Werewolf alternates its scenes of terror and suspense with humor both high and low, and often of the pitch-black variety. The Fly, meanwhile, represents the culmination of its creator’s knack for body horror, with Seth being the latest in a long line of hubristic scientists whose experiments backfire spectacularly. While American Werewolf is about making public spectacles—not just in the scene of mayhem in Piccadilly Circus that closes it, but also the one where David wakes up naked in the zoo after his first night out and has to somehow make it back to Alex’s flat with a modicum of his dignity intact—The Fly is primarily concerned with private suffering, as Seth turns into a virtual shut-in when his physical deterioration becomes apparent. Similarly, while Seth’s last-ditch effort to regain his humanity involves merging with his lover and their unborn child to become “the ultimate family”—a scheme heroically thwarted by his rival, Stathis—David’s last contact with his is a collect call home where he only gets to speak with his ten-year-old sister Rachel, whose inability to comprehend that he’s saying goodbye to her for good frustrates him just as he’s working up the nerve to slit his own wrists.

Ultimately, David can no more take his own life than Seth can—the latter because, as a scientist, he’s fascinated by the process and curious about how far it will go. (Remember the Brundle Museum of Natural History in his medicine cabinet?) They both also try to protect their loved ones by running away or scaring them off. Once he hears that his disturbing nightmares have become a reality, David tries to get himself arrested and, failing that, puts as much distance between himself and Alex as possible, not realizing she’s only trying to help him. Seth’s methodology, on the other hand, is more roundabout, as he confuses Veronica with ramblings about the nonexistence of insect politics and the fantasy that he’s been one all along before coming to the point and telling her he’ll hurt her if she stays. This does the trick and causes her to break down as she leaves him, but it’s not for the last time since both films end with the women in tears, confronted by the horrifying man/animal hybrids their mates have become.

At the close of American Werewolf, having clung to the belief that the stray, young American she brought home is merely suffering from the delusion that he’s a monster, Alex finds herself in the dark alley where David has been cornered, desperately trying to reason with an inhuman creature that has to be put down by the police before it can make her its next victim. As The Fly reaches its climax, though, Veronica knows all too well that she’s forever lost Seth to Brundlefly and personally pulls the trigger that puts the pathetic remains of the man she still loves out of his misery. Even the knowledge that she’s carrying his baby, which may have been conceived while he was still fully human, is little comfort to her. That’s the tragedy Cronenberg acknowledges with the slow fade to black and reprise of composer Howard Shore’s somber main title theme, which is a far sight more respectful than Landis’ jarring cut to black and the Marcels’ mood-dispelling doo-wop rendition of “Blue Moon.”