Split Diopter: Looking at Women’s Identities Through a Male and Female Lens

By Yasmina Tawil

It’s a common stereotype that men are known to be the more aggressive and competitive of the sexes, and that women are far coyer and subtler at the game. Studies have shown that women enjoy cooperation as much as competition, that they find symbiosis in their struggle for dominance. And it’s this complicated, nuanced relationship among women that has often been mined for great psychological cinema. Male friendships inspire buddy comedies and male competitiveness often manifests on the screen in a more literal way, such as through a sporting event, but with women, their bonding is often explored like a fever dream—as a merging of two identities, or one identity diverging into two. It makes for far more fascinating storytelling, but the end result is more often than not skewed towards the tragic.

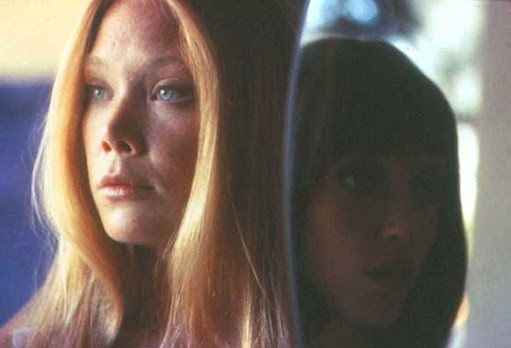

The examples are plenty. One of the earliest standouts is Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958), in which Kim Novak’s tragic heroine personas Madeleine and Judy send Jimmy Stewart’s Scottie Ferguson into a hypnotic spiral. In Robert Altman’s 3 Women (1977), roommates and coworkers Millie (Shelley Duvall) and Pinky (Sissy Spacek) swap dynamics, and thus dominance, after a climactic incident until they arrive at a new, strange means of co-existence. In Ingmar Bergman’s Persona (1966), the merging of identities between the inexplicably mute actress Elisabet (Liv Ullmann) and her nurse Alma (Bibi Andersson) is illustrated quite literally, with two halves of their faces joined together to form one. It’s nearly impossible to tell whose face is whose at this point, and what scenes are to be taken literally. Then the film burns. These movies can’t help but offer dual realities, too. In Persona and 3 Women, especially, dream sequences blur with real life, and they don’t exactly ask to be distinguished. (For Altman, the idea for the film came to him through a dream.) These movies almost seem to depict dark magic but they aren’t necessarily fantasy films.

The Guardian’s Steve Rose referred to these as “frenemyship movies” while critic Miriam Bale coined the term “persona swap films.” Bale writes in Joan’s Digest:

“These films […] are about the friendship between two people, usually women (often a brunette and blonde, and frequently one eccentric/dominant and the other more conventional) who swap personas. It is usually a story about two women, yet is differentiated in tone and logic from something like Thelma and Louise. That film is deliberately a buddy action flick starring two women; there is no swap of supple personality types and there is no magical merge. The films that belong in this subgenre have a recognizable, nonrealist tone, a dream logic. They’re psychological, supernatural and, at their best, illuminate very specific aspects of relationships between women.”

This theme of female identities—and the swapping, merging, and diverging of them—has been a prevailing theme in women-centric thrillers and dramas alike. Barbet Schroeder’s 1992 erotic thriller Single White Female used a makeover plot point for the identity swap moment, with Jennifer Jason Leigh’s character Hedy getting the same bob and dye job as her aspirational roommate Allie (Bridget Fonda). The film’s title has even become part of our vernacular—when you hear that so-and-so is “single white female-ing” someone, you know exactly what that means. Brian De Palma has dedicated a chunk of his filmography to this subject (see: 1973’s Sisters, 1976’s Obsession, 1984’s Body Double, 2002’s Femme Fatale) as did David Lynch (see: 1997’s Lost Highway, 2001’s Mulholland Dr., 2006’s Inland Empire, and both runs of Twin Peaks). Darren Aronofsky brought the theme to the already cutthroat world of ballet with 2010’s Black Swan—a dynamic that not only emerges between the two leads, Nina (Natalie Portman) and Odile (Mila Kunis), but also between Nina and the principal dancer past her prime, Beth (Winona Ryder), who is being replaced. (Beth is also credited as “The Dying Swan.”) More recently, there’s been Alex Ross Perry’s Queen of Earth (2015), about a diverging friendship that funnels its pent-up frustrations into Repulsion-esque mania, and Olivier Assayas’ The Clouds of Sils Maria (2015), with a subtler version of the Black Swan theme of an older woman being replaced by a younger protégée, both in life and the performance within the performance.

But all these movies have another thing in common: They were all directed by men. Perhaps it’s the notion that women use indirect aggression for romantic attention, that have caused curious frenzy in the minds of male filmmakers, but they continue to create and portray female characters who fall under this umbrella of twisted fate (one woman usually dominates or kills or attempts to kill the other, or they both get in trouble). It must be a frightening concept to men—this idea of women having a special bond, of women containing multitudes—and perhaps that’s why many of these movies carry a tragic tone. In a way, these films could be love letters to women, too. Men, spellbound by the secrets shared between women, can’t help but let their minds wander to the mysteries of their link—and while trying to chip away at it, they end up destroying it in their art.

Only very few women directors have depicted that kind of relationship between two women in such a tragic manner (see Josephine Decker’s 2013 film Butter on the Latch and Sophia Takal’s 2016 film Always Shine, which was an Oscilloscope release). Also rare are male persona swap movies; in Joan’s Digest, Bale gives Nicolas Roeg’s Performance (1970) as an example of such, but adds that “for men to enact the motions of this Persona Swap, they must first be feminized.” In Roeg’s film, they don make-up and a wig.

With the exception of Decker and Takal, women are usually less lethal in their portrayal of female friendships that deal with this persona swap. In research for this piece, I collected a large list of films about women and identity and noticed that as opposed to men, women directors were more inclined to make feel-good films about the joys of friendship, or some sort of comedy of misunderstandings. Examples include Vera Chytilova’s Daisies (1966), Susan Seidelman’s Desperately Seeking Susan (1985), Nancy Meyers’ The Parent Trap (1998), and Melanie Mayron’s TV movie version of Freaky Friday (1995). Two women who start acting like and becoming each other doesn’t have to be something tragic; it’s reminiscent of the dynamic between best friends. Daisies came out the same year as Persona and while it also plays out like a fever dream, too, with two women who seemingly become one, Bergman’s film is a frightening devouring of each other’s autonomies while Chytilova’s is a delightful us-against-the-world type romp. Women aren’t afraid of these close relationships between themselves; they feel stronger in union, life is more fun when together.

There’s truth to both ends of the spectrum, though. (Women, they sure contain multitudes). I’m not here to discredit the films made by men—some even have creative input from its leading actresses. Sure, there’s an inimitable euphoria of watching Daisies with your best girl friend, but ask any woman and they’ll likely find the motif of Persona or 3 Women or Single White Female familiar, too. Bale notes that “one or several of these films is on the list of the favorite films of virtually every woman director or film critic I know,” and that’s certainly true for myself. Takal’s and Decker’s films are especially fascinating because the female perspective is, to some degree, lived (even if Takal’s husband Lawrence Michael Levine wrote the screenplay for Always Shine). Good news is, this subgenre is endlessly fascinating and isn’t going away anytime soon—what I hope to see is more portrayal of women’s relationships on all ends of the spectrum, especially from more female creators.