ShockerProves that Even Wes Cravens Lesser Films Had Something to Sayby Keith Phipps

By Yasmina Tawil

When Wes Craven died on August 30, 2015, at the age of 76, most of his obituaries dwelt on three films: Last House on the Left, A Nightmare on Elm Street, and Scream. That’s understandable. Craven worked for decades and directed dozens of features. Yet, each in their own way, those three films changed the direction of the horror genre. They’ll be the ones for which Craven is best remembered, even if they don’t give a sense of the full scope of the highs and lows of his career.

Craven occasionally expressed regret that he didn’t get more opportunities to work outside the horror genre, whose confines he managed to escape for just two features: the Meryl Streep-starring 1999 drama Music of the Heart and the excellent 2005 thriller Red Eye (though the latter was packaged as a horror film via a misleading trailer). But even working within horror, Craven’s filmography contains a remarkable amount of variety. He smuggled a hard-to-miss satire of the Reagan/Bush era’s treatment of the underclass into The People Under the Stairs and used Wes Craven’s New Nightmare to turn the Nightmare on Elm Street series into a metafictional ouroboros. Horror was never just a job for Craven. He was always trying to say something.

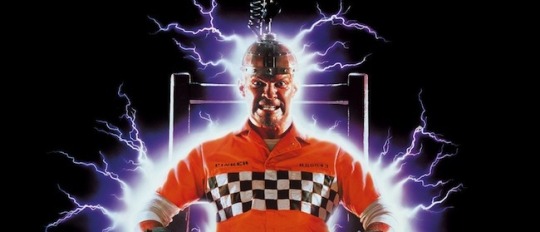

That’s true even of his lesser films. Released in 1989, Craven’s Shocker has its defenders, but defending it means looking past the film’s pokiness and familiarity. The story of a college football star named Jonathan (Peter Berg) and the brutal killer named Horace Pinker (Mitch Pileggi, now best known for his work on The X-Files) with whom he has a mysterious connection, Shocker takes a long time to get going and then winds up in some familiar territory once it does. Specifically, the film bears a strong resemblance to Craven’s own A Nightmare on Elm Street and, at its worst, to that film’s later, lesser sequels, which transitioned its bad guy, Freddy Krueger, from a terrifying bogeyman into sadistic wiseacre in an increasingly cartoony world. (Craven helped script, but did not direct, the series’ second and best sequel.) Jonathan helps defeat Horace partly by following him in his dreams. When Horace claims a victim, he does so with a quip and a smile amidst a lot of over-the-top fantasy sequences. Audiences could be forgiven a sense of déjà vu.

Those who turned out, that is: Released by Universal in time for the Halloween weekend, Shocker debuted to negative reviews and a poor box office. “It lives up to its title only intermittently,” Richard Harrington wrote in The Washington Post, typifying critical reaction. Meanwhile, more viewers turned out for the Ted Danson- and Jack Lemmon-starring drama Dad. Seemingly conceived to be the next big thing in an age of horror that coughed up one sequel-inspiring bad guy after the next, Shocker ended up being a footnote, both to the era and to Craven’s career.

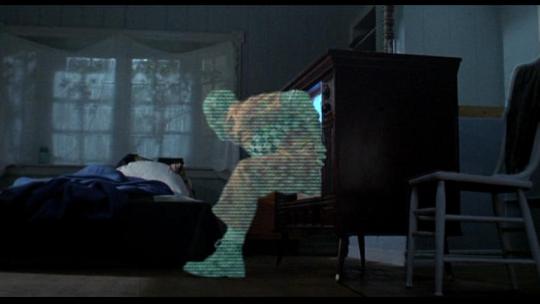

Yet there’s a lot of Craven in the film, even if it doesn’t rank among his best. Horace, a TV repairman by trade and a practitioner of black magic by choice, eventually dies after being executed by electric chair, only to return as a sort of electric spirit, able to take over the bodies of others and continue his killing spree—and his harassment of Jonathan and his adoptive police detective father (Michael Murphy) in particular. Horace also has a gift for jumping into and out of television sets, and in the film’s memorable, garish climax, he and Jonathan fight across a series of landscapes familiar to regular viewers of late-’80s television: a heavy metal music video, a rerun of Leave It To Beaver, a televangelist pleading for money (played by Timothy Leary), a newscast of global unrest, and so on.

In an audio commentary included on a new Blu-ray edition of the film, Craven notes he wanted to make a movie about “a world we all lived in but weren’t terribly aware of […] the world of electromagnetic impulses and the world of electronics and communications and the neural network of the modern world.” Had it been made a few years later, Shocker would have doubtlessly been set in some primitive, William Gibson-derived, 1990s understanding of the Internet. Instead, Craven drew on the best source for information overload he knew: television. There’s a TV on in many of Shocker’s scenes, often broadcasting some sort of awfulness the film’s characters have learned to ignore. When the police raid Horace’s lair, it’s filled with televisions seemingly set to an endless loop of the 20th century’s greatest tragedies. But, apart from the animal sacrifices, it’s not that different from every other interior in the film.

It’s a Craven film in other ways, as well. Eventually, Horace reveals himself as Jonathan’s father. Craven lost his ill-tempered father at an early age. “This whole film to me was kind of an exorcism,” he notes on the audio commentary, making no attempt to hide its autobiographical origins. Raised in a strict Baptist household, Craven would later attend a comparable strict college. He had little access to film until after graduation, when he began working as a humanities professor in upstate New York. Once he entered the world of film, he never left. And if Craven didn’t set out only to make horror films, he never wanted for ways to express himself within their confines, using horror as a way to talk about politics, and the way the sins of one generation exert themselves on the next, and how what we fear finds its way into our lives no matter how hard we try to shut it out.

The most frequently visited site of horror in Craven’s films is the bedroom. It’s where Freddy visits his victims in Elm Street. It’s a place that provides no refuge for would-be victims in the Scream films. It serves as an unsafe space in everything from Last House on the Left to The People Under the Stairs. Here it’s the place where Jonathan confronts Horace, and if that confrontation devolves into a less-than-thrilling fight during which Jonathan learns to control Horace with a remote control (and via some dubious-looking special effects) the scene still bears Craven’s signature. What we attempt to shut out, no matter how hard we try, will always find us, even where we sleep.