RKO 1952 PART III by Matthew Dessem

By Yasmina Tawil

A series examining the output of a single studio in a single calendar year.

SUMMER

As summer began, the split Hughes had opened up in the Screen Writers Guild began widening. Or, as the New York Times put it, “a new movement is under way within the ranks.” A writer named Theodore St. John wrote an open letter urging the union leadership to send Hughes another letter:

…telling him that he is legally 100 percent in the wrong…but going on to say that morally, he is, in our opinion, entirely in the right; and that, as we do not wish to press a legal right against a moral right, we are dropping the suit against him.

But with arbitration ruled out, the Guild had nothing to say about it until the matter reached the courts. Hughes, too, had run out of ways to escalate the situation. Which meant his film studio was left with nothing to do except release movies.

RKO didn’t have many other hidden gems tucked away in their vaults, but there was The Wild Heart, which was almost a wonderful film. In fact, it had been a wonderful film, in England, in 1950, when directors Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger released their original cut under the title Gone to Earth. Unfortunately for American audiences, the film had been co-produced by David O. Selznick, who took a particular interest because it starred his new wife Jennifer Jones. Selznick was at least as much of a memo writer as Hughes, and perhaps worse, since he dictated his memos under the influence of amphetamines. Powell and Pressburger simply filed them away and made the film they had in mind.

Like their masterpiece The Red Shoes, Gone To Earth is the story of a woman pulled in impossible directions until something snaps. In this case, Cyril Cusack and David Farrar were doing the pulling, as Jennifer Jones’s emasculated husband and her oversexed pursuer, respectively. Jones herself plays a half-gypsy girl with deep ties to nature and magic. It’s the kind of subject matter that can easily become ridiculous, but Powell and Pressburger—better than perhaps any other directors at keeping dark shadows and danger in fairy tales—manage to pull it off, with more than a little help from Christopher Challis’s gorgeous Technicolor cinematography. But Selznick hated it; they hadn’t paid any attention to his memos. When the directors refused to make the changes he wanted, he sued them, lost, and finally made the changes himself, recutting the film and hiring Rouben Mamoulian to shoot new scenes (including, naturally, more close-ups of his new wife). It was Selznick’s compromised version that RKO brought to theaters, to no great acclaim or success.

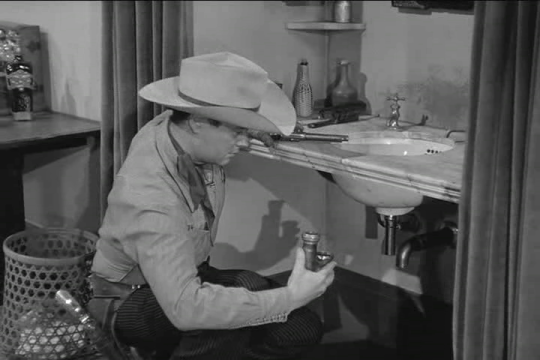

The Wild Heart was followed by Desert Passage, the last of a long series of B-Westerns starring Tim Holt. The series had been struggling to find its way for a while; Target, earlier in 1952, featured a lengthy sequence in which Holt finds a critical clue in the trap beneath a sink. Even if they hadn’t been stretching to find new things for Holt to do, B-Westerns were moving to television by this time. Next, RKO distributed Disney’s The Story of Robin Hood and His Merrie Men, which has nothing particularly wrong with it, but is the sixth-best-known Robin Hood film for a reason. August began with One Minute To Zero, a mediocre Korean war film starring Robert Mitchell. RKO showed no signs of life all summer, until Sudden Fear, one of the two independent productions that had been shooting in January, opened in New York.

Joseph Kaufmann had nominally produced the film, and David Miller directed, but it was a Joan Crawford project from start to finish. She’d selected the screenwriter, director, cinematographer, composer, and cast Gloria Grahame and Jack Palance as the villains. The casting turned out to be a mistake, at least as far as a pleasant working environment went. Palance and Grahame were having an affair during the location shoot in San Francisco; Grahame didn’t like Crawford, so Palance snubbed her too. But even though rumors of on-set fighting leaked out, the dislike may have fueled the performances. Crawford, who’d hired the two younger actors before discovering they didn’t much like her, plays an aging playwright who marries the much younger Jack Palance before discovering he and Gloria Grahame not only don’t much like her, but are planning to murder her. Whatever she was drawing from, Crawford is extraordinary (and Palance and Grahame seem like they’d genuinely enjoy murdering her). Sudden Fear is formally inventive, too, from the nearly dialogue-free finale, pure silent storytelling, to the heartbreaking scene Crawford plays against a Dictaphone, in which the sound is everything. Sudden Fear would go on to be nominated for four well-deserved Academy Awards.

Nothing in the rest of the month was quite as good, but August was still an exceptional month for the studio, especially compared to the rest of the summer. There was Beware, My Lovely, another noir-tinged thriller with Ida Lupino and Robert Ryan, and The Big Sky, a solid Howard Hawks Western with Kirk Douglas in the John Wayne role. For most of the summer—in fact, for most of 1952—RKO seemed like a place where good films only got made by mistake. In August, unexpectedly, it looked like a studio again. So Howard Hughes sold it.

FALL

The first press rumblings had come in April, shortly after the production shutdown, although there’d been rumors for months. Variety reported that representatives of Louis B. Mayer and Howard Hughes had been meeting to discuss the possible sale of the studio. Mayer had been forced out at MGM the previous summer. (Dore Schary, who reportedly engineered Mayer’s ouster, was at MGM because he’d been forced out at RKO by Howard Hughes, and round and round we go.) Even with its declining revenues, RKO must have been an attractive acquisition prospect for someone who wanted to make movies as much as money. Hughes was offering all of the infrastructure and very little of the staff, and with no productions filming, whoever bought the studio wouldn’t be saddled with any legacy productions from the old regime. The Mayer deal had fallen through, but when the story broke in September that Hughes had found another buyer and closed the deal, it wasn’t a complete surprise. The surprising part is who he’d sold it to: a syndicate headed by Ralph Stolkin, the president of Empire Industries, a Chicago mail order firm.

If selling a film studio to a “syndicate based in Chicago” sounds a little suspicious, Hollywood thought so too, though not for the obvious reason. There was only one thing more frightening than organized crime to a film studio in 1952, and that was television. Stolkin owned pieces of companies involved in every stage of television production, from a TV/film production company to broadcast stations to the manufacturer of cathode ray tubes. The initial Los Angeles Times story about the sale called it “Television’s first big bite into motion picture product distribution” and quoted this analysis from a “well-informed stock market operator”:

“It is not at all certain that the potential purchasers will be interested in operating a studio. Their aim is to secure the reserve of RKO productions with a view to using these in any manner in which they see fit, and quite naturally that suggests television.

Both Hughes and Stolkin sought to reassure the town when the deal was officially announced. “The buyers have assured me that they will pursue a program of top-grade production of motion pictures,” said Hughes. Stolkin was blunter, telling reporters, “We want to make it clear that at this time we have no intention of releasing any of the studio’s stock of film for TV.” But even with television fears assuaged, the fact remained that no one in the film business had any idea who Stolkin and his associates were. The Washington Post made the first attempt to clear things up, publishing a glowing profile on October 5 that—with very few details—outlined Stolkin’s “meteoric rise.” The Post’s version was a Horatio Alger story about a 34-year-old wunderkind who turned a $15,000 loan into a fortune, mostly through the sale of ball-point pens. The piece ended on an up-note, with oil coming in on one of Stolkin’s wells—he’d invested his ballpoint money in oil—on Easter Sunday. “I’m getting sort of suspicious about holidays,” the Post quoted Stolkin as saying, “as they’ve been good luck for me.”

October 16 is a holiday now—“Boss’s Day,” appropriately enough—but it wasn’t in 1952, surely the unluckiest day of Ralph Stolkin’s life. “RKO’s New Owners: Background on Group Which Now Controls Big Movie Maker,” the Wall Street Journal headline read. So far, so good. But then came the subhead, “A Punchboard King, A Mail Order Charity Mogul, and a Gambling Oilman: Learning the Picture Business.” The article itself is a remarkable piece of writing, as dry as the Gobi:

Assurance can now be given, however, that some members of the group which took over from Mr. Hughes are remarkable men in their own right. They deserve to be much better known than they are.

What follows is an absolute shellacking of everyone involved in the deal, however peripherally, from Stolkin himself down to the lawyer who made the initial introductions (Sydney Korshak, who, the article noted, “like many another honest citizen” kept getting mentioned in testimony during the Kefauver organized crime hearings). After thumbnail sketches of all the major players, the article featured a detailed profile of Abraham Koolish, Stolkin’s father-in-law and a newly minted director of RKO. Stretching back over two decades and drawing on records from the Better Business Bureau, the FTC, and the federal courts, the article sketched a lengthy history of shady dealings: mail-order punchboard gambling that never paid winners, shoddy chinaware sold under false pretenses, life insurance that wasn’t. Just the list of shell corporations was damning: the Journal tracked down “the Lincoln Novelty Co., Atlas Premium Co., Chicago Mint Co., Pierce Tool and Manufacturing Co., Montrose Silk Co., and Garden City Novelty Co.” all sharing an address with Koolish’s punchboard company. Worst of all, the article closed with an ominous promise:

Further adventures of Mr. Koolish and his associates will be related soon in another article.

The next day the spotlight was on Texas oilman Robert Ryan. Per the Journal, he was an inveterate gambler with close ties to “Prime Minister of the Underworld” Frank Costello, in federal prison at the time. The article also suggested his wells produced more laundered money than crude oil. The Journal took the weekend off, and by Monday, other papers were tracking the story. Stolkin and company had an emergency meeting in Chicago on Monday, and scheduled a board meeting for Tuesday the 21st in New York (pre-telepresence days; the West Coast members got on a train Friday to make the meeting). But transcontinental trains moved much slower than scandal, and as Stolkin made his plans in Chicago, the Journal banked the fire with a profile of the man himself. The lede is brutal:

The rocket rise of Ralph Stolkin to the presidency of RKO Pictures Corp. can only be explained in these terms: Unusual energy. Uncommon imagination. Unceasing use of the U. S. postal system.

Stolkin’s money, like Koolish’s, came from selling punchboards, mail order games that promised prizes to winners that were rarely or never delivered. But Stolkin got special attention: the Journal dug up Better Business Bureau warnings that quoted the parents of the children he had cheated. The next day was the board meeting; the company’s chairman, Arnold M. Grant, held a press conference, “to which the Wall Street Journal was not asked,” the Journal noted in its coverage, under the headline “RKO Pictures’ New Chairman Says Losses Are About $100,000 A Week.” The day the story ran, Stolkin, Koolish, and Robert Ryan’s board representative William Gorman all resigned from RKO, citing “unfavorable publicity.”

Meanwhile, back on the lot, things continued falling apart. Jerry Wald’s relationship with Norman Krasna had deteriorated over the years as they tried and failed to get films past Hughes, and his relationship with RKO was essentially open warfare by this point, as Richard Jewell explained:

The Wald-Krasna people were making notes about… every time they asked for a meeting and how long it took to actually set one up; the RKO people were making notes about all of the things that Jerry Wald in particular was doing without authorization from the head man.

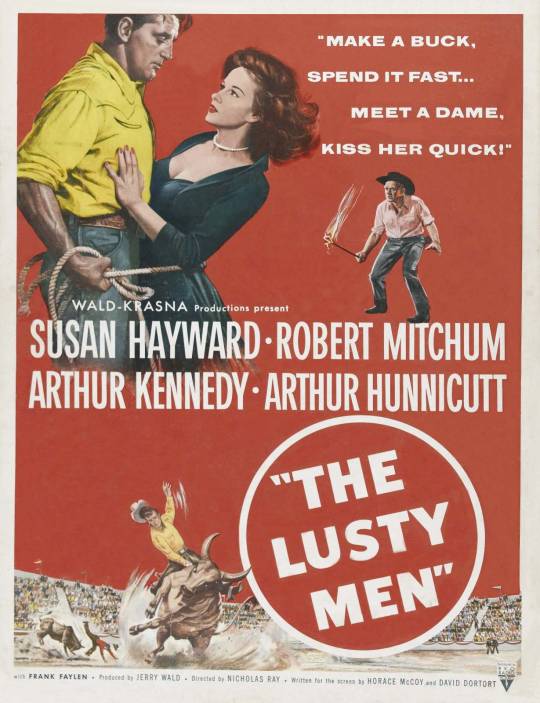

As RKO plunged into turmoil, Wald saw his chance, and asked for the immediate cancellation of his contract. He got it. His escape had been well-planned; released from RKO on a Monday, he was a VP at Columbia by Wednesday. On his last weekend as an RKO employee, the final Wald/Krasna film premiered in San Antonio: Nicholas Ray’s The Lusty Men. Hughes had promised that Wald and Krasna would produce 60 films. This was the fourth.

But Wald left on a high note. The Lusty Men is as brutal a deconstruction of masculinity as was ever made, and RKO’s best film of the year. It stars Robert Mitchum as a broken-down rodeo rider and Arthur Kennedy as his protégé; Mitchum wouldn’t make a film that interrogated his own screen persona so thoroughly again until The Friends of Eddie Coyle in 1973. In fact, the entire film has a tone and rhythm that feels closer to the 1970s than the 1950s; like Fat City, it’s set in an exhausted world. And it has the rarest of things in a film about masculine rivalry, a well-drawn female character in Susan Hayward. It’s one of the only times the last gasp of a failed business partnership—released while both Wald/Krasna and RKO were in freefall—turned out to be a masterpiece.

RKO’s ongoing collapse, which had nothing to do with the quality of their films, continued apace. If Stolkin thought his resignation—or “labor consultant” Sydney Korshak’s a few days later—would stop the Wall Street Journal’s crusade, he was rudely awakened on the 28th, when they profiled Stolkin’s charitable work through his direct mail corporation, Empire Industries. The numbers were fascinating—Empire had raised money for one such charity, the National Kids’ Day Foundation, in the amount of $650,626.50—and charged them $652,585.32 for the privilege. The Journal was kind enough to do the math: “the public had chipped in nearly two-thirds of a million dollars, but the foundation appeared $1,958.82 poorer.”

Things weren’t any better for the people who’d remained at RKO. The board fell to infighting: chairman Arnold Grant resigned in mid-November when the other members wouldn’t second his nominations for board members to replace the people who’d resigned. Stolkin and his associates still owned the stock they’d bought from Hughes, but with no one on the board, they no longer had a say in what the company did. It wasn’t clear if anyone was at the helm at all anymore.

Meanwhile, Paul Jarrico finally had his day in court—but not much more than a day. RKO’s preemptive suit and his countersuit, combined into one action, opened on November 17 and were decided before Thanksgiving. RKO made the argument that by refusing to answer questions about his political affiliations — he’d made himself the subject of “public disgrace, obloquy, ill will or ridicule” — violated the morals clause in his contract, and forfeited the right to ask for anything. Jarrico’s lawyers argued that a clause that nullified the collective bargaining agreement he had worked under couldn’t be valid. The judge heard the case through closing arguments—Hughes even emerged from his seclusion to testify—but found in Hughes’ favor without deliberations the second the lawyers finished. Taking the Fifth Amendment when asked about Communism, the judge ruled, was enough to convince the public someone was a Communist or Communist sympathizer, disgraceful enough that no other contractual rights mattered. Jarrico got nothing for his trouble except Howard Hughes’ contempt—which, to him, wasn’t nothing. “I was proud to have him as an enemy. A man’s known by his enemies as well as his friends,” he told Patrick McGilligan decades later.

The decision put the Screen Writers Guild in a bad position—Hughes had clearly, brazenly ignored their contract, but the ruling made it clear that neither the public nor the courts were likely to intervene. Furthermore, the longer the Guild stood up for Jarrico, the more the public would come to view them as a suspect organization. It was in this context that the union declined to join Paul Jarrico as amicus curiae in any further appeals, because, per The New York Times, “it is extremely sensitive about the political issues which have overshadowed the basic legal question.” Just how sensitive they were became clear the next April, when they voted to give up their right to determine writing credits, allowing producers to summarily delete the name of anyone who was either a Communist or refused to answer questions about the matter. The clause would remain in the union’s contract until 1977.

And things just kept going Howard Hughes’ way. The Stolkin syndicate wanted out of RKO, no one else wanted in, and by December they were practically begging Hughes to buy their stock back. Actually, not even buy it—take it off their hands. They’d purchased it with a $1.25 million down-payment on a price of $7.25 million. If Hughes would take the company back, they’d let him keep the entire down-payment. By December 15, the stock and the company were back in Howard Hughes’ control. As with RKO’s game of chicken with the Screen Writers Guild, it’s a little hard to sort out why the entire affair happened. The Wall Street Journal stories were published very quickly and were very well reported, and the paper had shown no interest in Stolkin’s shady dealings until he bought RKO. It seems likely that someone was feeding them the story. The most likely candidate, and the subject of many rumors, was the man who’d made $1.25 million for not selling his film studio. But Richard Jewell reports seeing a memo that indicated Hughes was trying to discover who had leaked the information, so this doesn’t seem to be the case. As the Journal stories made clear, the men had no shortage of enemies; there’s no way of knowing.

The studio hadn’t stopped releasing movies during all this chaos, but nothing that stood up to August’s high points. There was Face to Face, a two-part anthology film: one entry features the acting of James Mason and the other the acting of James Agee, so it’s a little unbalanced. Charles Vidor’s Hans Christian Andersen, a musical starring Danny Kaye, was their holiday entry. Androcles and the Lion, Chester Erskine’s adaptation of the George Bernard Shaw play, is the best of a mediocre bunch, perhaps because of Nicholas Ray’s uncredited reshoots.

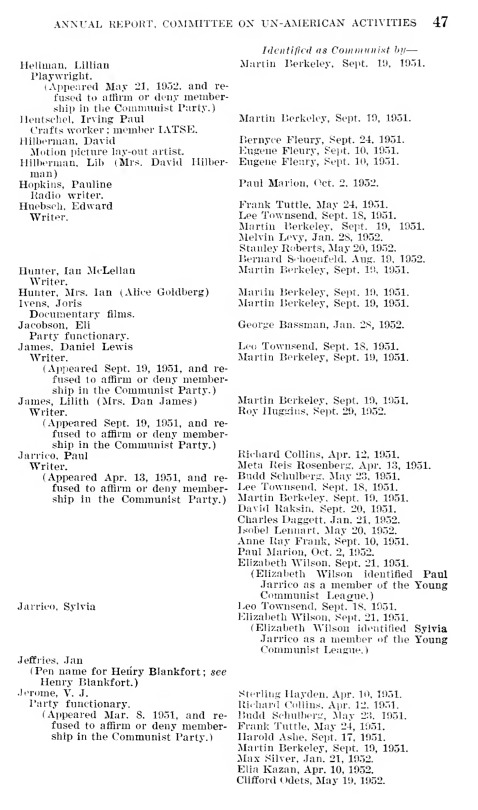

But the last significant release in RKO’s 1952 schedule wasn’t a film at all. On December 28, the House Committee on Un-American Activities published its annual report, half victory lap, half wish-list. By its own account, the Committee had done a great deal to expose Communist infiltration in the industrial centers of Detroit, Chicago, and Philadelphia, youth groups nationwide, the Army Signal Corps Intelligence Agency, the Methodist Federation for Social Action, and, of course, Hollywood. But there was still important work left to do, if only intelligence-gathering laws could be relaxed and the Espionage Act could be modified to allow the death penalty in peacetime instead of only when the country was at war.

But what made the 1952 report special were its appendices: following each area the Committee had investigated was a list of everyone who had been named before the Committee as a past or present member of the Communist Party. The Hollywood Ten had appeared in previous reports, of course, but this was different: alphabetical by last name, cross-indexed, and, most thoughtfully of all, with a second column that, for each suspected Communist, included the names of everyone who’d given them up, as well as the dates of the hearings in which they’d done so. This section wasn’t only a government-approved blacklist—it was a list of confessions designed to generate more confessions.

By the end of 1952, HUAC had moved beyond any pretense of intelligence gathering and into full-on degradation ceremonies. The biggest obstacle to any purge is the stigma attached to informing; publishing the list of informers was a public declaration that the committee recognized no such stigma, both an assertion of power and a self-fulfilling prophecy. In 1951, even friendly witnesses like Larry Park thought of testifying as “crawling through the mud.” By the hearings in March of 1953, the Committee was noting a new “spirit of helpful cooperation” throughout the motion-picture industry, as the list got longer and more lives and careers were destroyed. Neither RKO nor Howard Hughes began this process, but they certainly helped it along. For the rest of the decade, fear and recrimination and backstabbing would hold illimitable domain. The blacklist outlived Hughes Aircraft’s transport helicopter contract, which the Air Force cancelled a few months after the Korean War ended. It lasted longer than RKO itself: Howard Hughes ominously sold the studio to the General Tire and Rubber Company in 1955 and production finally shut down in 1957. The blacklist even lasted longer than Paul Jarrico’s membership in the Communist Party. He was out by 1958, after “even the slowest of us realized that the accusations against Stalin and Stalinism were true… and that we had been defending indefensible things.” But he never ceded the point that his membership in the Communist Party was anti-American.

…I personally didn’t find a contradiction between the interests of the Soviet Union and the interests of the United States. I thought the Soviet Union was a vanguard country fighting for a better future for the entire world, including the United States. That was an illusion, I discovered. But the illusion didn’t make me disloyal; it made me a fool. And that’s what I wound up feeling like. Not that I’d been deceived, but that I’d deceived myself.

By the time Dalton Trumbo’s name reappeared on screen in 1960, the sole survivor from the RKO of 1952 was the missile Hughes Aircraft had been developing that year, by then renamed the AIM-4 Falcon. It was still in use in Vietnam, where it didn’t work. When it was replaced with the Navy’s internally developed AIM-9 Sidewinder, all that remained of RKO’s mad year were the films, many distorted and compromised by Howard Hughes’ obsessive tinkering and the hysteria coming from Washington. The Lusty Men is great, though.