One Man, One Bullet: The Politics of Lindsay Andersonby Judy Berman

By Yasmina Tawil

Mick Travis sits alone in his study, his back against a wall plastered with war photos, shooting a dart gun at images hung up on the opposite wall: a womans naked body pasted atop a line of police in riot gear, a sleeping family, Big Ben, the queen in her carriage. Though he never says as much, these are all symbols of institutions that wield power over him. The upper-crust boarding school where Mick is a student is another; in the next scene, his younger classmates are whipped into a subtly terrifying frenzy over an athletic victory. Back in the study, Mick and his friends Johnny and Wallace drain a bottle of vodka and take a blood oath to each other, before Mick utters his famous line: One man can change the world with a bullet in the right place.

These four minutes of Lindsay Andersons 1968 film if. provide a concise, if intentionally provocative, summation of the British directors politics. Like so many other filmmakers who came to prominence in the 60s, Anderson thought in revolutionary terms. What set him apart was a wariness towards ideological regimes of all kindsand the masses who subscribe to themthat transcended the decades defining right vs. left, old guard vs. young avant-garde split. If you want a continuity of theme, I think this is one, Anderson wrote in a diary entry his lifelong friend, the writer Gavin Lambert, quoted in his book Mainly About Lindsay Anderson:

a mistrust of institutions and an anarchistic belief in the importance of the individual to make his or her decisions about liferather than simply accept tradition and the institutional philosophy.

Its a worldview Anderson developed most effectively in a trilogy of films starring Malcolm McDowell as the protean Mick Travisa character who changes so drastically and inexplicably from if.to O Lucky Man! (1973) to Britannia Hospital (1982), he might as well be a different person in each one. More than Micks personality, what connects these works is their evolving assessments of the state of Britain at three points on a 14-year timeline.

Their pointed social commentary has earned the films (and their director) a reputation for being very British and exceedingly of their time, but thats a superficial judgment. In our current age of economic strife and malignant populism, Andersons satire feels far less dated than the idealism of his 60s contemporaries. Watching the trilogy now, in the US, it couldnt be clearer that in pointing out the absurdity of one place and period, they captured a brand of political absurdity that couldnt be more contemporary.

Perhaps this is a strange thing to say about a movie that ends with a massacre, but if. is the most optimistic of the three films. Mick Travis, in his original incarnation, is the archetypal teenage rebel. In his first big-screen appearance, 24-year-old McDowell earned his Clockwork Orange role by tempering youthful anger with a magnetic grin and icy blue eyes so alert, they make everyone else in the frame look half-asleep.

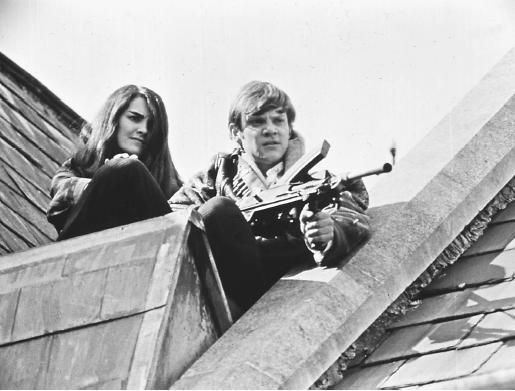

As the ringleader of a trio of outcast Crusaders, Mick is targeted by a band of older boys known as Whips who constitute the schools lowest but cruelest layer of authority. Though the Crusaders do break rules, from drinking to taking a joyride on a stolen motorcycle, its their iconoclastic attitude that poses the greatest threat to the school and ultimately leads the Whips to exact corporal punishment on them. Its a humiliating enough experience that when they stumble upon some guns, Mick, Johnny (David Wood), Wallace (Richard Warwick), and Micks fiery love interest (Christine Noonan, playing a character known only as The Girl) decide to put his philosophy into action. if. culminates with a Founders Day fire that forces a parade of parents, administrators, clergy, and a visiting military official out of the school building and into the Crusaders crosshairs. Perched on the roof, these heavily armed individuals finally have an advantage over the sea of conformists on the ground.

Its an uncomfortable scene to watch nearly 50 years later, in a country where gun violence kills so many and school shootings are among the most terrifying strains of that epidemic. Mick Travis could so easily be just another unhinged young white man who believes the minor indignities hes suffered justify ending dozens of lives. And Im not sure Anderson, who made Micks ideology grotesque enough to be at least somewhat off-putting, would entirely disagree with that assessment. The whole world will end very soonblack, brittle bodies peeling into ash, Mick tells Johnny and Wallace at one point. War is the last possible creative act.

But if. was released at a time when schoolboys gunning down authority figures would have been viewed as a metaphor, not a snapshot of reality. Just months after the May 68 riots, the Crusaders would have looked like young radicals rising up against the oppressive regimes of government, religion, and school in the only way available to them. You dont have to squint much to see them in that light now.

Theres a perverse sort of hope embedded in this ending: if institutions are the enemy of individual freedom, at least we have the power to resist them through nihilistic acts of destruction. The fact that some version of the character appears in two additional films isnt conclusive proof that Mick survives his massacre; Andersons own doubts that hed get off the roof in one piece proved an obstacle for an abandoned 80s if… 2 project. Still, Mick is alive when the credits roll. It isnt exactly War is over! (If you want it), but its the closest Anderson got to being swept up in the spirit of the 60s.

Half a decade later, when he reunited with McDowell and if. screenwriter David Sherwin for O Lucky Man!, the era of student radicalism was over and Andersons point of view had grown even darker. In this surreal portrait of Britain, every attempt at beating the odds stacked against the individual proves futile. The epic three-hour picaresque remakes Mick Travis as a jovial, newly minted coffee salesman whose sole objective in life is to become a success. Anderson, a Brechtian who did more work in theater than in film, interrupts the narrative with musical interludes featuring songs composed and performed by Alan Price of The Animals. Although O Lucky Man!s hero never quite absorbs the lessons life is trying to teach him, Prices sharp commentary ensures that they reach the viewer.

Everywhere he goes, innocent Mick gets a warm welcome followed by what should be a wake-up call. An accidental drive onto military property leads to Micks apprehension and interrogation; his captors torture him until he confesses to a crime he didnt commit, then flee in advance of an explosion that nearly kills him. As a medical research subject, he cheerfully bargains his way to a higher fee only to jump out the window after encountering a fellow patient whose human head is pasted onto the body of a hairy, four-legged animal. Things finally seem to be looking up for Mick when he lucks into a job as the assistant to an ultra-wealthy businessman, Sir James Burgess (Ralph Richardson). Hes even willing to overlook the imperialists extralegal dealings with a repressive Third World dictator. But, of course, Sir James is setting up Mick as his patsy. When the authorities swoop in, our hero is the only one to get arrested, tried, and sent to prison.

A conventional critique of capitalism might end here, with the revelation that the system corrupts and eventually crushes even the most earnest seekers of success. But O Lucky Man! continues after Micks release. Now that hes read enough philosophy to become enlightened, he vows to be unselfish. People are basically good, he decides; its poverty that makes them do bad things. So he tries, unsuccessfully and at great risk to his own safety, to stop a poor mother from committing suicide. He volunteers to feed the homeless, only to be attacked by them. A bit of graffiti near their camp reads: Revolution is the opium of the intellectuals.

Mick ends up at a casting call for a film called, yes, if., where he questions the direction of none other than Lindsay Anderson. O Lucky Man! concludes there, with a full-cast dance party that seems to celebrate Micks first expression of a will beyond whats imposed on him by all forms of authoritythe capitalists and the humanists. Its a joyful conclusion to a film that, unlike if., attacks liberal orthodoxy almost as viciously as conservatism. But Micks victory over years of populist brainwashing is a limited one. Hes not destroying the institutions that oppress him, or even their representativeshes just learning to think independently of them. Its worth considering why this revelation comes during an audition for a film. Sure, individuals can express themselves through art, but is there any space for free thought in the real world?

Early in the Thatcher era, Anderson, Sherwin, and McDowell moved from disillusionment to full-on absurdity. Rushed into production after years of gestation, Britannia Hospital is less notable for its narrative than for the series of darkly comic tableaux it sets up. Considering that Anderson embraced a TV-commercial aesthetic for the film, that may well have been the point.

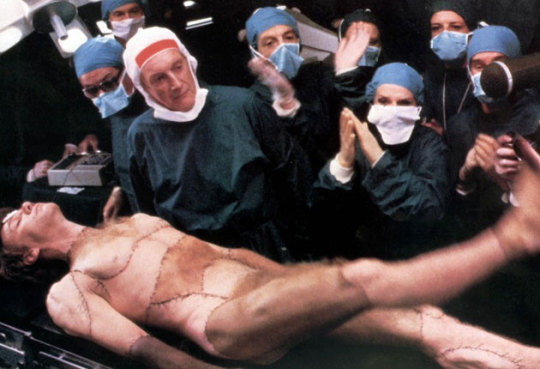

As its name suggests, the hospital is a metaphor for a Britain that has devolved into a clusterfuck of competing groups and agendas. Britannia is beset by protesters, crippled by a strike, exploited by the media, governed by out-of-touch aristocrats, bursting with patients who believe their wealth should buy them better care, in thrall to technology, and awaiting a visit from the queen. If Mick Travis fate is a barometer for Andersons mood, wellin Britannia Hospital, McDowells character is an amoral journalist who gets his head sewn onto the body of a Frankenstein-style monster before meeting a gruesome end. His final act of rebellion is to bite the megalomaniacal Professor Millar (Graham Crowden), who reduced him to a patchwork parody of a human being. The film ends with a triumphant Millar introducing another of his creations: an enormous mechanical brain that he believes represents the future of humanity.

Unlike if. or O Lucky Man!, Britannia Hospital took its inspiration straight from the headlines. Lambert recalls Anderson telling him that the idea originated with a news story he read about a labor union that struck to protest the admission of paying patients to a free public hospital. Pickets actually refused to admit ambulances with emergency cases, or delivery vans with medications that the lives of some patients depended on, he told Lambert. Nice idea for a comedy, dont you think?

Particularly in England, critics balked at the negativity of Andersons prognosis for their country. But for Lambert, Britannia Hospital was a flawed yet effective culmination of the filmmakers point of view. Satirizing every kind of institutionalized power, political and scientific, labor and the media, the film comes down emphatically on the side of individual power, he writes, arguing that for Anderson, only human intelligence can create a wiser world.

That wiser world becomes an ever more remote possibility with each successive film in the trilogy, as the individual grows increasingly powerless to break free of authority figures, the institutions they represent, and the mindless mobs they control. Anderson, who died in 1994, never missed a chance to rail against the selfish cruelty of capitalism, but he didnt have much patience for democracy either. Its a rare stance whose merits are obvious in 2016, a year whose headlines could inspire their very own Britannia Hospital. In the US, democracy and capitalism have conspired to make a rich, bigoted reality TV star a viable candidate for the presidency. Last week in Britain, the hazards of democracy became catastrophically clear when a conservative PMs selfish act of political theater backfired in a popular vote to leave the EU.

The only flaw in Andersons politics is that, even at their most optimistic, his films never quite offer a vision of what a society governed by human intelligence would actually look like. Democracy and capitalism may be a dangerous combination, but could the absence of both offer us anything more than teenagers with guns, screaming salvos from a rooftop?