Not Mad, Just Disappointed: Mothers on the Edge in the ‘70s and Present by Charles Bramesco

By Yasmina Tawil

Starting in the early ‘70s right on through to his departure in 1982, showbiz executive Ned Tanen turned Universal Pictures into a hotbed of creativity, throwing respectable budgets at daring, original directors and meeting with box-office success more frequently than he didn’t. This halcyon era of studio-sanctioned risks yielded American Graffiti, Animal House, Jaws, and The Deer Hunter, and positioned Universal as an exemplar of New Hollywood’s ethic of innovation and experimentation. One of the lesser-known beneficiaries of Tanen’s permissive doctrine was director Frank Perry, who used his authorial latitude to pull off a pair of vital releases that would have otherwise been a difficult sell, to put it mildly.

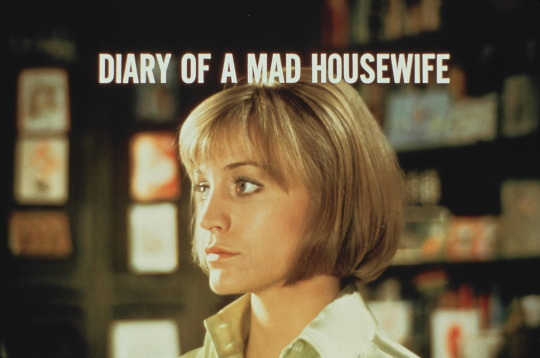

Sister films Diary of a Mad Housewife and Play It As It Lays could have only been made in the ‘70s, when their disillusioned, harshly critical, even accusatory stance happened to be in vogue. Their subjects live relatively similar lives and chafe under roughly the same social pressures: two women, both beset on all sides by unfeeling husbands, manipulative lovers, and children they can’t connect with. Alongside contemporary filmmaker John Cassavetes and his Gena Rowlands-led masterpiece A Woman Under the Influence, Perry spearheaded a small movement of pictures focused on the hazardous expectations placed on mothers, and the deleterious psychological effects they can have. They established a tradition that still lives on today in such fine films as Xavier Dolan’s polarizing Mommy and Trey Edward Shults’ recent feature debut Krisha. But as the world and its dominant attitudes towards maternal duty have evolved, so too has the way this micro-genre interfaces with its subjects.

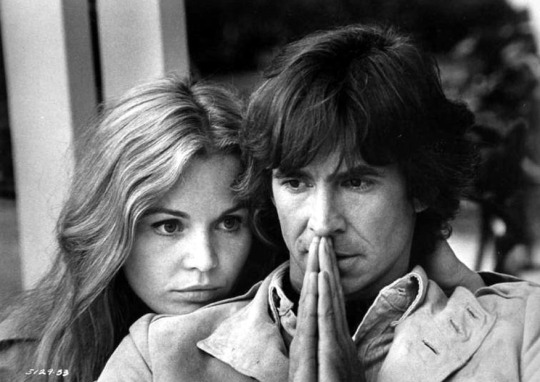

Perry’s nervous-breakdown diptych and most of Cassavetes’ collaborations with Rowlands were strongly informed by the tenets of second-wave feminism, and its aspirations to reconfigure the woman’s role in the home and other social spaces. Play It As It Lays adapted Joan Didion’s novel about an actress named Maria (played with total commitment by a tremulous Tuesday Weld) contending with a slow-moving divorce from her vindictive producer husband, a rotating carousel of equally unfulfilling sexual flings, an unstable daughter cooped up in a sanatorium, and a chronically depressed best friend played by Anthony Perkins. Likewise, as mad housewife Tina Balser, Carrie Snodgress is stuck with one of the worst husbands in cinema history in Richard Benjamin’s sniveling social climber. He treats her like an all-in-one servant-hooker-secretary, when not actively and deliberately abusing her. To make matters worse, her offspring is a nasty-tempered little brat who openly berates Mom at every opportunity.

Trapped in their own lives, losing a tenuous grip on sanity, these women buckle under the pressure from the key figures in their lives to fulfill their proscribed mold of womanhood. The dominant feminist ideology of the time sought to abolish that mold, to accept that women could be autonomous sexual beings (both films feature lovingly shot sex scenes and cold, dispassionate rutting in equal measure) and needn’t be shackled to the framework of a nuclear family unit. Affording the women in these films the leeway to fail in their capacity as mothers (or in the example of Meryl Streep’s Joanna in Kramer vs. Kramer, abdicate the position entirely) was Perry and Cassavetes’ most radical move. Most importantly, the women have no functional system of support; Maria is drugged up and mistreated when her husband commits her to a mental facility, and Tina gets nothing but apoplectic yelling when she tentatively sits in on a support group. These films forcibly reclaim the masculine archetype of the hysterical woman by positing the protagonist’s heartrending breakdowns as the only logical response to the stifling constant performance of subservient marriage and motherhood.

Both Perry and Cassavetes devised novel formal means to convey their characters’ mental states as well. Tinkering with spatial perception does an effective job of communicating the sensation of being trapped; both A Woman Under the Influence and Diary of a Mad Housewife assume an intimate naturalism, shooting their subjects in close-up and often assuming their perspective either literally through POV shots or implicitly through framing sympathetic to the protagonist. In one of Play’s more haunting shots, Perry takes the opposite tack and pans out from a medium-wide shot of Maria cruising down a SoCal freeway in her yellow Corvette until the whole of creation comes into view. She’s shrunk down to a speck, flying haphazardly through a world in which everyone seems to know where they’re going but her.

Four decades later, directors continue to pursue this topic, employing modern technologies to push formal boundaries. Krisha director Trey Edward Shults filmed his account of one women’s utterly ruinous Thanksgiving with gliding long takes that mimic star Krisha Fairchild’s narcotized drifting through her family’s home. French-Canadian enfant terrible Xavier Dolan ruffled quite a few feathers when he chose to film almost all (key word being “almost”) of his two-hour-plus melodrama Mommy on a 1:1 aspect ratio, mimicking the square dimensions of an Instagram post. While many harsher critics cried foul and slapped the director with charges of adolescent formalism for its own sake, a more charitable read would note how the narrowing of a frame emphasizes faces and bodies instead of landscape. Dolan imposes a claustrophobia on the harried Diane (Anne Dorval, fabulous even as she approaches total collapse) and her wild-child son Steve (Antoine-Olivier Pilon) that reflects how constricted their dead-end lives are. He blocks out everything in a shot but them, and in one exhilarating moment, allows the pair a glimmer of hope by opening up the frame.

And just as the means through which these modern-day “unwell mother” films present their women grew more sophisticated with time, so too did the specific nature of their turmoil. America has matured quite a bit in the years since Perry and Cassavetes—the concept of a woman having thoughts of her own, pursuing her own career, or opting out of life with a family no longer draws the gasps it used to. Both Mommy and Krisha revolve around mothers losing control of themselves, and yet the male figures of oppression are markedly absent. There are no cruel husbands or callous lovers, no impositions from external forces apart from the various social workers pleading with Diane to keep her son under control in Mommy. What’s more, both Krisha and Diane have systems of support in place; the rest of Krisha’s family is rooting for her to move beyond the addiction and alcoholism that’s estranged her from her siblings and child, and Diane’s friendly neighbor Kyla (Suzanne Clement) does what she can to ease the load with homeschooling Steve.

The terms of these central conflicts have been somewhat de-politicized, rendered more internal than external. If Perry and Cassavetes’ films map a woman’s clash with her time, their spiritual successors map a woman’s clash with herself. Krisha and Diane are unable to accept the help offered to them, forced instead to confront their personal shortcomings when they realize their problems are no one’s fault but their own. The easing of societal mores has lent these films a more ambiguous, complicated relationship with their characters—the beleaguered mothers of the ‘70s experienced victimhood under a suffocating patriarchy, but in our relatively advanced present, women like Krisha and Diane must search somewhere more obscure for the source of their depression.

For Perry’s mothers on the verge, a woman’s work was defined as a happy home, a satisfied husband, and an apple-cheeked youngster. One wave of feminist thought later, and it’s boiled down to the universal and gender-nonspecific impulse of self-preservation. The original bad moms fought for autonomy in and outside the household, and while present-day characters have continued those efforts, their war for independence has also taken on an existential tinge. In some cases, nothing can fill the hole at the center of their being.