No Future: How Richard Linklater and Eric Bogosians SubUrbia Foreshadowed Donald Trumps AmericaBy Russ Fischer

By Yasmina Tawil

Disappointment is powerful and insidious. When an object of desire slips away, particularly something we believe we deserve, the sense of loss can be intense. It’s not that we failed to get something; that thing was taken from us. The characters in Eric Bogosian’s 1994 stage play SubUrbia, and the 1996 film version by Richard Linklater, boil with this disappointment—for perceived promises unfulfilled, for the stacked odds against fame, success, happiness. The emotion is transmuted into a sense of victimization, and anger.

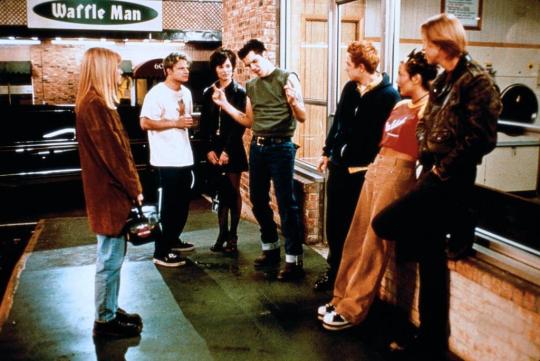

The venomous spit of SubUrbia wasn’t out of place in 1996 as the mainstream accommodated an influx of indie culture in the arts, but the film played like the bitter b-side to Linklater’s sunnier Dazed and Confused. What can we glean from a bunch of malcontents, high school friends now in early adulthood, who express feelings of futility and pain plus racism as they drink away their nights in a parking lot? Few of the characters are likable, with many exuding an odious sense of entitlement. This skewed snapshot of the stereotypically disaffected Generation X has largely fallen off the radar, in part due to years of poor home video availability, despite Linklater’s growing reputation as a major American filmmaker.

Looking at the film anew two decades years later, SubUrbia howls with middle-American anxiety, the same voices that have been resounding through political rallies for the past six months. This movie is more than a mid-’90s time capsule: It’s a potent advance warning of the crippling sense of American loss and failure that fueled the political rise of Donald Trump.

Trump courts a voter base made up of a spectrum of Americans dissatisfied with economic status, security, and race relations. The long-since eroded American middle class—adults whose early 20s might have looked a lot like characters in SubUrbia—is his feeding ground. He galvanizes moderate and conservative voters without college educations who believe they’ve been abandoned by a system skewed toward elites, especially in racially tense states. Only a bit of clever editing would be required to make SubUrbia look like a Trump campaign ad.

As a precursor to the abrasive post-rock soundtrack that accompanies most of the film, Linklater opens SubUrbia with the more gently ominous “Town Without Pity” by Gene Pitney. “How can anything survive?” in a place like that, Pitney sings. Indeed, as so many citizens we see in fictional Burnfield, Texas turn their anger and frustration outward, rather than devoting energy to fixing their own problems, we watch what little community they have wither away.

Linklater doesn’t tame Bogosian’s characters (the playwright scripted the film), but the director’s slowly roving camera reveals sympathetic notes in the small-town group of friends, who hang out near a convenience store drinking and talking and harassing the store’s immigrant owners. Linklater amplifies the humanity of the going-nowhere characters without diluting their bile. Several may be unlikable, but they are not at all inscrutable.

The most strident town crier of dissolute American Dreams is Tim (Nicky Katt), a discharged Air Force pilot. Mean-eyed, with a bushy, grown-out crew cut, Tim haunts the side parking lot of a convenience store, off to the side near the dumpster. He’s the alpha ringleader for a trio filled out by pizza shop worker Buff (Steve Zahn, reprising the role he originated on stage) and layabout Jeff (Giovanni Ribisi).

Katt imports the brutish bravado of his Dazed and Confused character Clint (who beats the hell out of Adam Goldberg’s nerdy Mike), contributing to the sense that SubUrbia is a mirror image of Linklater’s earlier film. The scorched-earth suggestion of the town’s name is echoed by Tim’s virulent outlook. He’s a needler, a provocateur, and the most expressly racist of the film’s would-be rebels.

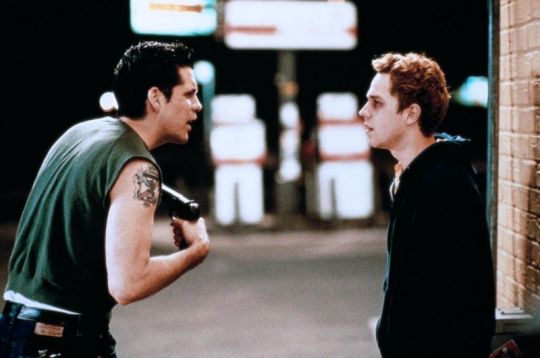

Behind Tim’s smirk and hair-trigger anger is a sad awareness of his pathetic behavior. His depression and sense of failure are sublimated into impish goading of his friends, and he’s blatantly aggressive toward Nazeer and Pakeesa, the Pakistani operators of the convenience store Tim treats as his playground. Once a promising athlete and military recruit, he’s become a drunk bully willing to wield a pistol as a threat, blaming immigrants for the job and success he failed to attain. “I was born here, I’m an American,” he insists, “and I’m owed something. They took it from me.”

So many hallmarks of the modern “alt-right” are embedded in this instigator: open, reactionary racism; jealousy; an embrace of gun culture; and an understanding of language and psychology as weapons. Uniting it all is that disappointment, the sense of opportunities lost and intangible factors spinning out of control.

These traits run deep in America. Their expression in SubUrbia, and the surge in the political sphere of 2016, are points on a continuum. Yet these parking-lot rats aren’t cut from the same cloth as political conservatives. Theirs is the image of “alternative” ‘90s counterculture, soundtracked by Ministry and Sonic Youth. These kids rail against the system like young progressives. They could have been something different, and seeing how quickly their own looming failures have limited their outlook, they fall back into anger.

In this regard, Bogosian’s standout creation is Sooze, played on film by Amie Carey. Her outrage is rooted in youth, love, and sexism; her romantic relationship to Ribisi’s character Jeff is fading along with any motivation he has to succeed. As a budding performance artist, Sooze is informed by the Riot Grrrl movement but lacks introspection. She proclaims idealism and a desire to raise consciousness about “sexual politics, racism, the environment,” yet her nascent third-wave feminism hasn’t quite developed to include empathy for Pakeesa. Sooze’s stomping performance art, culminating with cries of “Kill all the men!” doesn’t translate to action when faced with Tim’s racism.

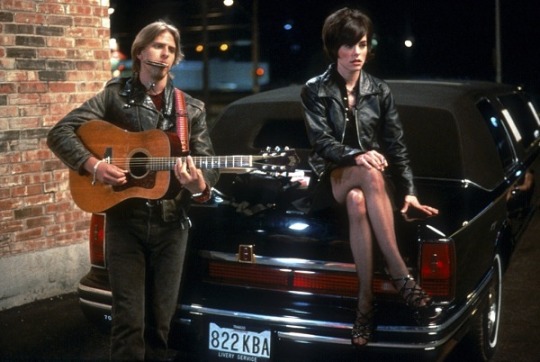

Sooze falls under the spell of Pony, the town’s closest thing to a celebrity, when he swings by the convenience store after a local gig. He’s a high school nerd turned shaggy-haired musician, enjoying a brush with fame thanks to MTV; his new status, however, is likely to fizzle quickly if his limp songs are any indication of his future. To Sooze, even a hint of success is more than anyone in Burnfield can offer.

Lanky Jayce Bartok plays Pony with a grinning, earnest ease, as if Wiley Wiggins’ young Mitch from Dazed and Confused grew up to be a pop star—or as if Linklater himself ended up on a different path. The filmmaker’s own experiences shape his movies more than most, and Pony’s status as an analogue for the director adds an ironic layer to the character’s wan creativity and aw-shucks approach to fame.

Even the successful are disaffected, as Pony idolizes the relatively low-stress Burnfield life he left behind to become a rock star. “You guys are real,” he enthuses, ignoring their ugliness and disdain. The soft-rocker invites the audience’s scorn; we can see, especially with the benefit of hindsight, how limited Pony’s future is likely to be. Jeff perceives Pony’s pathetic nostalgia and flips out a bit as he takes stock of his own limitations. “I can do anything I want,” he rants, “as long as I don’t care about the result.”

Narratively, SubUrbia stumbles in its final third, when Tim’s sexual impotence turns his manipulative machinations into a big plot twist. (In order to retain some sense of suspense for those who’ve yet to see the film, we’ll simply say an unsuccessful sexual encounter seemingly ends in violence.) The turn nearly works because we’re so ready to believe this agitator would do such horrible things.

Jeff believes that Tim may have become a monster; when the truth comes into focus, Tim scolds Jeff for falling into the same credulity we experienced as an audience only minutes earlier. “You’re gullible and you’re gutless,” he says. In this supremely smug moment, Katt practically auditions to play Trump in the inevitable biopic of the mogul/candidate’s life. Like an entomologist pinning a specimen, Tim precisely targets Jeff’s weakness, and our own.

We want to believe the worst about Tim. That dark gullibility, when applied as a general rule, engenders a worldview where we fall prey to suspicion and fear. As with so much of SubUrbia, this idea is pushed toward an extremity—a vision of America very much like the political landscape of 2016, where disappointment and resentment guide emotional reactions, where the demagogue seems like a natural leader.

Burnfield, this town without pity, might have been an outlier, just a good place where things all went bad. Is everyone living with this unease, their disillusionment festering? “You want to believe so bad,” as Tim says to Jeff, “you’ll buy anything.” Even if that means buying into the wrong thing.