Map of the Human Heart: My New York in Nick & Norahs Infinite Playlist and They Came Together by Vadim Rizov

By Yasmina Tawil

For ten years now, I’ve nursed an oddly specific theory: Nick & Norah’s Infinite Playlist is the most geographically accurate film about New York City, at least within the last 15 years. This is a strange thing to fixate on, not least because the film doesn’t come up much: It came out a decade ago, received generally fine reviews, and made $33 million (at least in part because it was riding the post-Juno/Superbad wave of Michael Cera’s newfound fame), but if it’s become a cult film, that’s one quiet cult. None of this is relevant to what’s valuable about the film: Nick & Norah’s primary task is, yes, to tell a linear teen romance narrative in the “one crazy night” subgenre. Its secondary imperative is to make sure that every time someone crosses a street or turns a car, the geography is accurate. That’s way more important to me, in part because it’s rarer than I’d like.

This is not the kind of thing that would have popped out at me before moving to New York. I grew up in Austin from 1993-2004, at a time when Texas was getting serious about introducing tax incentives to increase film production, but the movies shot in town and released while I was still growing up didn’t offer much in the way of lived, on-the-street experience. One of the first big productions to shoot in and around (definitely more the latter) Austin was 1998’s The Newton Boys. If memory serves, the film bricked nationwide but played there for a few months; it’s nice to see your city onscreen, a privilege many places don’t get, so people rolled out. But The Newton Boys is a period film, so there wasn’t much to latch onto recognition-wise, with the exception of a scene shot in the Paramount Theater (a 1915-built Art Deco theater, of the type you can find all over the country, where I spent far too many summers watching the building blocks of classic Hollywood cinema) and a few set-dressed street exteriors around it. There’s Office Space, of course, but the goal there was to present a vision of a generic any-city—and most of it takes place indoors, anyway. Some local excitement was mustered for Wing Commander (shot in Luxembourg, post in Austin) and hometown hero Robert Rodriguez’s Spy Kids; this isn’t the richest pool to draw upon. (Please don’t bring up Slacker, it’s too complicated to get into.)

I moved to New York in 2004. NYU unexpectedly met my financial scholarship needs, which was supposed to give me four years to transition into living in the city, which ended up happening. One of the first things I did after arriving was go see Thom Andersen’s 2003 doc Los Angeles Plays Itself, which I’d read a lot about but had not been able to access in Austin. Andersen’s nearly three-hour essay film on representations of Los Angeles on screen is an excellent, game-changing thing to watch in college, but perhaps what stuck with me most was the section in which Andersen (via narrator Encke King) bitches extensively about geographical inaccuracy: how distracting it is to watch a film shot in Los Angeles and see a character make a left turn that relocates them three miles away in a single cut. It’s not the kind of thing non-natives would be likely to notice, but once you’re on the hunt for it, it’s endlessly aggravating, as Andersen demonstrates in a montage of nonsensical examples. It was something I’d never thought about, and something that has subsequently been wildly distracting every time I watch a film shot where I live now.

It is, perhaps, sad that I know for a fact that there is no Dunkin’ Donuts in Times Square, but nonetheless there is one in Men in Black III, digitally inserted for product placement reasons. That’s doubly infuriating: Setting aside the cynicism of the motivation, it takes one of the most unbearable places in Manhattan and actually make it worse. And not to pick on Will Smith exclusively, but Collateral Beauty contains one of the most baffling subway errors I’ve seen. Smith and Helen Mirren are having a conversation on the street, approach the Broadway-Lafeyette station and take one of the four orange lines (the B/D/F/M—it doesn’t matter which if you’re only going one stop uptown, and I couldn’t tell) one stop, to West Fourth Street. They emerge from the subway car and step onto the right platform, keep talking, walk up the stairs onto the right street—and when they turn the corner, they’re back at Broadway-Lafayette. Not only is this wrong, it’s simply baffling; both locations were clearly visited, so why not stick the landing for one more shot? This isn’t just some kind of pedantic score-settling that should be noted on an IMDB goofs page; I live here, and it’s insulting.

Not Nick & Norah’s though. The film came out in October of 2008, the first fall after I graduated NYU, and I immediately noticed that the film is scrupulously accurate about the NYU Freshman Universe. Because NYU bought up so much property in the West Village and adjacent areas (one of the many reasons why they are widely despised by locals, which I wish I’d known before applying), any freshman living in the dorms on campus is most likely going to stay confined to a certain area: 2nd to 6th Ave., 14th St. to Houston. Nick & Norah’s is slightly more expansive than I remembered, starting a few streets south of Houston, at Arlene’s Grocery on Allen St., and roams all the way up to Avenue A. Still, with the exception of a few trips out of the area (to Penn Station, uptown at the end and to “Brooklyn Pool”—actually Williamsburg’s locally infamous Union Pool, which the protagonists rightly leave quickly), it’s all in the same pocket I thought it was, and every move from one location to another makes sense. Rewatching the film, I took extensive notes on every turn and walk and could map it out; it’s nearly flawless in that sense. (One exception I caught: a right turn onto 10th Ave from Ave. A. Cera and Kat Dennings argue as he drives, until he suddenly U-turns back into A out of frustration. Realistically, they’d be closer to Ave. C or so at that point. If that’s the only problem, we’re not doing bad—the IMDB goofs page notes another three, only one of which I registered and is indeed weird, but none of which strike me as unforgivable.)

I might not have clocked the accuracy quite so intently if it weren’t for where the movie stops for a few minutes: the Modern Gourmet, a bodega around the corner from my freshman year dorm, Brittany Hall. I know the space well; on a very limited budget, there were a lot of dinners cobbled together from the hot bar (discounted after 8 p.m.!), a mélange of heat-counter dumplings, sausage and peppers and pasta shells, a combo whose taste will never leave my mouth. This is where Norah’s rests for a key scene, and when Dennings comes back outside, the van where people are waiting for each other is parked on 10th St., right where it should be. That remains moving to me: A not-outstanding year of my life preserved in a succinct image that, plot-wise, has nothing to do with me.

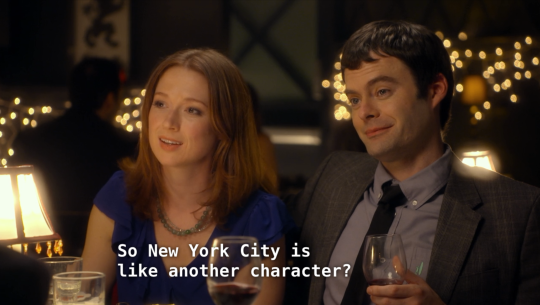

If Nick & Norah’s is the most geographically accurate NYC movie, there must be a least accurate counterpart. For that, I’ll nominate They Came Together, David Wain’s exhaustive 2014 dismantling of (among other things) You’ve Got Mail. The geographical scrambling is by design and sometimes impossible to ignore: even if you’ve never been to New York, it’s hard not to notice the discrepancy when an exterior shot of The Strand—the sprawling new-and-used bookstore/clearinghouse that claims to stock eight miles’ worth of books—cuts to the interior of a tiny bookstore that definitely isn’t the Strand. It’s actually Community Bookstore, in Brooklyn’s Park Slope; one of the film’s incredibly specific jokes is that it theoretically takes place in the Upper West Side, but was blatantly shot in Brooklyn (in Brooklyn Heights and Cobble Hill, specifically). In most movies, geographic inaccuracy is the result of laziness, inattention, or just plain not caring; in They Came Together, that’s a whole visual joke that goes absolutely uncommented on. If you don’t live here, you might not notice; if you do, it’s impossible to unsee. The movie leans into the joke hard: the very first scene riffs on an old chestnut of these kinds of films, with the line “There is another character that was just as important as the two of us: New York City.” Heighten the contradictions.

If one film’s goal is explicitly to get geography right and the other’s is to derange it, what’s strange to me is which of the movies I now find more authentic in its portrayal of NYC. When I saw Nick & Norah’s upon initial release, I guessed that part of the reason it was shot in NYU-land is because director Peter Sollett went there as well. After rewatching it, I emailed him to ask about my ten-year-old hunch. “It sure was,” he wrote back. “After NYU I lived in the East Village for a decade, and my aim was to present the corner of New York that I love so dearly.” Accuracy was always the aim: “I know this is probably limited to people who live in Manhattan or have lived in Manhattan, but it always takes me out of the movie when someone takes a left on 14th Street onto [Houston] Street,” he noted in a 2008 interview. “It does suspend my suspension of disbelief […] and it didn’t seem necessary.” Wain’s goal was precisely to suspend that suspension: “We were commenting on how often NYC movies ignore obvious geographical realities that any New Yorker would notice,” he wrote in an email to me. “The entire movie is supposed to take place in the storybook version of the Upper West Side we associate with Woody Allen/Nora Ephron, etc., but was shot entirely in Brooklyn Heights/Cobble Hill. My favorite example of this was when we’re at the coffee shop in Brooklyn Heights outside the Clark St. subway station but we changed the [subway] sign to be the (non-existent) ‘Upper West Side’ station.”

I don’t doubt Sollett’s sincerity of intent or love for the area, but I’m guessing our experiences at, and relationship to, NYU are pretty different. It’s not worth getting into (at least not here) why I wasn’t the biggest fan of the school, but one thing I thought from the moment I entered the dorms was, “This is the only time in my life I will be able to afford to live in Manhattan.” I was correct: When I moved out of the dorms in 2007, I went out to Brooklyn and have been here ever since, and it doesn’t seem like that’s going to change any time in the near future. Nick & Norah’s is a movie that’s comfortable with privilege (Dennings’ character turns out to come from serious money), and there’s nothing inherently wrong with that. But Nick & Norah’s Manhattan was never going to be mine, and the final shot is a little unnerving: craning up over 8th Ave, outside Penn Station, with the camera and sun rising to optimistic music. The effect should be a real “I love New York” moment, but I can’t get over knowing that that block is anything but pleasant, and the shops whose signs we see (Chase, Fidelity Insurance, the mini-chain Europa Cafe, which is basically in the Pret category) speak to the increasingly homogenous nature of that area in particular and NYC in general.

If They Came Together’s New York is a construction that deliberately doesn’t work, in some ways it’s closer to my reality: people whose aspirational lifestyle is to live in Manhattan but can’t afford it (not that the Brooklyn neighborhoods the film was shot in are at all cheap, or even particularly “affordable,” insofar as that word even still has a discernible meaning in contemporary NYC). They Came Together is the present and future; Nick & Norah is my past, seen in a nicer light than I might personally cast on it. We are all lucky to be able to have a chance to see the place we live onscreen, and some of us are more often lucky than others; we’re luckiest of all when someone sweats the details.