Long After Midnight: The Curious Story of Shock Treatment, the Rocky Horror Picture Show Sequel Designed to Attract a Cult Following That Never Arrivedby Keith Phipps

By Yasmina Tawil

Last year, The Rocky Horror Picture Show, celebrated its 40th anniversary, a landmark marked by a cast reunion, online retrospectives, a new Blu-ray edition of the film, and news of a planned TV remake for Fox featuring, among others, original star Tim Curry. And, of course, there were the usual celebrations via the midnight gatherings of fans who dress-up, talk back to the screen, and reenact the film as it plays on the screen behind them, a still-thriving tradition even as the landscape of midnight moviegoing shifts. This October will see the arrival of another, related, anniversary, albeit one sure to pass without much fanfare: the release of Shock Treatment, a Rocky Horror sequel that arrived in theaters in 1981. But instead of assuming its place alongside the original, it lives deep in the shadow of Rocky Horror, beloved by a few, shunned by others, and unknown to most of the world.

To understand what Shock Treatment didn’t become, it’s necessary to first consider what Rocky Horror did. It’s an unlikely series of events that led to The Rocky Horror Picture Show turning into a sensation, then an institution: a combination of a specific group of talented creators and a general set of cultural trends. Raised in New Zealand on a steady diet of horror movies and comic books, the English-born Richard O’Brien returned to the country of his birth in the early-’60s and attempted to make it as an actor. As O’Brien tells it in the 1995 documentary The Rocky Horror Double Feature Show, he fell into writing almost as a happy accident:

“It was the very first thing I’d ever written and I didn’t even see it as writing, really. To me it was just like doing a crossword puzzle or painting a picture or making a collage. I just wrote some songs, which, I liked. I wrote some gags which I thought were funny. I put in some B-movie dialogue and B-movie situations and I was just having a ball.”

The resulting play, The Rocky Horror Show, opened on London’s West End in June of 1973, under the direction of Jim Sharman. With a cast that included O’Brien, Patricia Quinn, Nell Campbell (a.k.a. “Little Nell”), and, in the central role of Dr. Frank N. Furter, Tim Curry, the show became a smash. It also attracted the attention of Lou Adler, an American music manager and promoter who attended a show with his girlfriend, the actress Britt Eckland.

Smitten, Adler acquired the American theatrical rights and opened The Rocky Horror Show in Los Angeles, importing Curry to star in the production. In L.A., the show earned new fans — including Elvis Presley — and its success allowed Adler to strike a deal with 20th Century Fox to turn the play into a film. Filming commenced in England in October of 1974, with Sharman at the helm and Curry, Quinn, Campbell, and O’Brien reprising the parts they’d originated. Joining them were the American singer Meat Loaf, who’d been part of the L.A. cast, and Susan Sarandon and Barry Bostwick, actors cast in the roles of the whitebread couple Janet Weiss and Brad Majors at the suggestion of Fox, who wanted American actors for the parts.

After filming wrapped, The Rocky Horror Show then moved to Broadway where, ominously, it flopped. So, too, would the film when released in September of 1975 under a slightly new title: The Rocky Horror Picture Show. An ill-received preview screening in Santa Barbara led to a timid roll-out and a canceled Halloween opening in New York. It looked like the lights would go down on The Rocky Horror Picture Show before most of the U.S. had a chance to see it.

Some quick thinking by publicist Tim Deegan changed that. “He noticed,” critic Jonathan Rosenbaum writes in the 1983 book Midnight Movies (co-written with J. Hoberman):

that the few people who liked the movie were actually brimming over with excitement and gratitude afterward, as if it had been a revelation for them. This response led Deegan to suspect that the movie might not be a lost cause, and that an investment of some effort in its promotion might pay off in the long run.

To that end, Deegan, working with fellow publicist Bill Quigley, arranged for Rocky Horror to have its belated New York opening at the Waverly Theater in Greenwich Village in April of 1976. The strategy worked better than they ever could have anticipated and midnight openings in cities nationwide followed, also to considerable success. And so a film that seemed destined to disappear took root.

In retrospect, however, it now seems inevitable that RHPS would find an audience. The time was just right for it. O’Brien’s show tapped into decades of rock and roll rebellion in general but drew most directly from its most recent disruption in particular: glam rock, which coupled unapologetic (if sometimes purely performative) queerness with power chords and, in the years before punk, seemed like the greatest threat to the status quo music had produced since Woodstock.

In his 1998 film Velvet Goldmine, director Todd Haynes stages a kind-of alternate universe version of glam. Jonathan Rhys Meyers plays Brian Slade, a stand-in for David Bowie, whose sexually ambiguous, outrageously costumed early-’70s persona made him the focal point for glam. Watching a Slade press conference in which Slade tells a group of reporters he’s gay, future journalist Arthur Stuart (Christian Bale) imagines himself pointing at the TV and announcing to his parents “That’s me!” It’s a moment that echoes one of the turning points in Bowie’s career, a 1972 appearance on Top of the Pop performing “Star Man,” a track from his then-new album The Rise And Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars. It’s a dynamic performance that takes on added resonance when Bowie stares at the camera and points at those on the other side of the glass as he hits hits the lines “I had to call someone / so I picked on you.” For a certain kind of viewer, those who felt like outcasts thanks to their sexuality or whatever else inside them that made them understand they didn’t fit in, it played like an affirmation.

Sometimes culture works as a dog whistle, calling out to those who can hear it while going unheard by the masses, and as it was with glam, so it was with Rocky Horror. “Rocky Horror Picture Show,” Haynes told me in a 1998 interview, “incorporates a lot of the themes and has a kind of following like no film ever made in the history of cinema. Which is strange: You still can’t quite put your finger on why. But it certainly tapped into something.” What that “something” is no doubt varies from fan to fan, but there’s no ignoring the pansexuality at the heart of The Rocky Horror Picture Show, a sense of acceptance for pleasure and love in all their forms and a rejection of repression. In the process of paying homage to vintage science fiction and horror movies, the film also teases out the queerness, kinks, and sensuality never that far beneath the surface of the genres.

Much credit belongs to Curry’s performance as Frank N. Furter, too. In fishnets and lipstick, Curry cuts such a beautiful, androgynous figure, it’s easy to imagine him seducing both Brad and Janet. Borrowing more than a little from Bowie, Curry’s performance transcends camp. He never winks, never takes Furter’s quest for pleasure less than seriously. When he sings “Don’t dream it, be it,” what could sound like a bumper sticker instead has the ring of a call to arms.

****

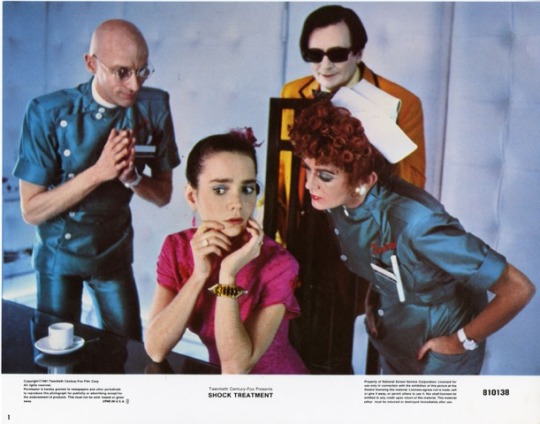

That O’Brien and Sharman would find interest in following it up once it became a staple of midnight screenings was, if not inevitable, highly likely. Shock Treatment began as a direct sequel, with Frank N. Furter resurrected, Janet giving birth to his baby, and all the other major characters returning. It arrived looking only tenuously connected to what had come before. Gone were Curry, Sarandon, Bostwick and most others. Returning were Charles Gray (Rocky Horror’s criminologist/narrator), O’Brien, Quinn, and Campbell. For Shock Treatment, however, they’d assume different roles,. And though Rocky Horror’s Brad and Janet would remain central characters, they’d be played by different actors, namely Cliff De Young and Jessica Harper (the latter no stranger to cult films having previously starred in Suspiria and Phantom of the Paradise). Also on board: Australian comic Barry Humphries (best known for his comic creation Dame Edna Everage), and Young Ones star Rik Mayall.

Gone too was Rocky Horror’s crumbling gothic castle. In its place: Brad and Janet’s hometown of Denton, Ohio, nicknamed “The Home Of Happiness” and a town now more or less consumed by the sprawling, antiseptic TV studio of DTV. Consequently, despite Sharman’s return as director, it looked little like Rocky Horror Picture Show. And despite O’Brien and Richard Hartley penning the songs, it didn’t sound that much like it either. Where Rocky Horror had deep roots in the glam era, Shock Treatment’s songs are new wave to their core, combining pop songcraft with synthesizers, propulsive guitar lines, and nods to American roots music and reggae. If O’Brien had Bowie on the brain while working on Rocky Horror, Shock Treatment seems to have born of long nights listening to Blondie.

But even if it looked and sounded little like RHPS, its core story wasn’t that different. For the now-married Brad and Janet, DTV becomes a dangerous and seductive world as they fall under the sway of a charismatic, possibly malevolent leader. Instead of Frank N. Furter, however, it’s Farley Flavors (also played by De Young), who’s spun his fast food fortune into the DTV empire, creating an endless succession of corporate-sponsored programming that ranges from game shows to soap operas, all enacted by the residents of Denton. As the film progresses, Janet becomes a star, Brad becomes institutionalized, and convoluted secrets get revealed. (Also as with RHPS, the plot can be confusing at times.)

So why didn’t it connect with Rocky Horror fans, much less a wider audience? It’s possible that, for all it had in common, its differences were too great, be it the changes in cast, the claustrophobic set, or the shift in musical style. It might also be that cults can’t be manufactured. They just have to happen. The rituals around Rocky Horror evolved organically. Shock Treatment arrived with the expectation of cultdom. In the Deseret News, critic Christopher Hicks wrote:

I may be naive, but it seems that a cult film becomes a cult film because a relatively small audience grows to love it and demands repeat viewings. Will such an audience allow a major studio to take a first-run picture and make it a cult film?That’s just what Twentieth-Century-Fox is trying to do with Shock Treatment, and since the movie itself is a raucous spoof of media manipulation, wouldn’t it be ironic if that studio succeeded?

It might have been. But it wasn’t. Fox enlisted Rocky Horror fan club president Sal Pirno to help promote the film, but he hit a wall, both with fans and with his own enthusiasm. On the official fan club site, he writes:

In New York City, while we were firmly implanted at the 8th Street Playhouse, Shock Treatment was booked Friday and Saturday nights at our old home, the Waverly, just a few blocks away. Shock Treatment did develop its own floor show and audience participation by a group of fringe people from the Eighth Street Playhouse. They were not very successful and came under much criticism (especially in an article in the Village Voice), by those who said that their participation was forced and not like Rocky Horror.

Which isn’t to say he, and others, didn’t like the movie. On the contrary, he continues, “Many Rocky fans, as myself, loved Shock Treatment, the music, the characters, the satire.” And yet, “Even though I have seen it only twenty times (‘only’ becomes a relative word here), I have never felt compelled to yell a single line back at it.”

There’s also this: Rocky Horror Picture Show is ultimately a movie about youth, sex, and the promise of freedom. It’s filled with characters who shimmy out of their repression and embrace a previously unconsidered world of possibilities, sexual and otherwise. Frank N. Furter may end up dead, but not before initiating Brad and Janet into a world much bigger than Denton. And yet, here they are, back in Denton, tied down in a marriage that doesn’t work and singing about that instead. Duetting on “Bitchin’ in The Kitchen,” they lament, to a succession of gleaming appliances, that their marriage has turned into a cycle of fighting. Later, Janet sings “In My Own Way,” the closest the film has to a love song. (A sample of the lyric: “If you could sleep nights / Stop your crying / Then you might find out I still love you / In my own way.”) In another song, “Looking For Trade,” the best Brad can do is occasionally interject he’s looking for love while Janet, head swollen with TV stardom, prowls for a young lover.

They’re songs of discontentment and disillusionment, not the sort of themes that easily lend themselves to singing, costumed crowds after midnight. (Any audience member experiencing a “That’s me!” moment probably didn’t want to celebrate it.) But here’s the thing: They’re pretty great songs. With Shock Treatment, the songs came first, some of them even dating back to O’Brien’s earlier conception of the film as a more direct Rocky Horror sequel and retrofitted to the new narrative. And if the film built around them sometimes feels a little patched together and the action a little dull between musical numbers, the same could be said of Rocky Horror.

The film also deserves credit for prescience. “Spoofing television is a pretty stale tactic by now,” Kevin Thomas complained in the Los Angeles Times, “and TV as a target, for all its dangerous excesses, isn’t nearly as much fun as old horror pictures.” [NB: The article linked to above misidentifies the date it ran as 1978.] But what Thomas couldn’t have known in 1981 — over a decade before the debut of The Real World and more than two decades before YouTube and the rise of the Kardashians — was how common Janet’s transformation into a raging narcissist would become, or how far the concept of famous-for-being-famous would extend beyond Andy Warhol’s factory.

Maybe that’s why Shock Treatment has experienced a little bit of a renaissance in recent years, even reaching out a bit beyond the cult-within-a-cult of Rocky Horror fans who admire it. It was revived as a London stage musical to strong reviews. O’Brien suggested it would fit right into a landscape filled with “these dreadful people coming into our lives … famous for nothing.” And while at this point it’s clear that it will never match its predecessor’s stature, it deserves to be more than just a footnote in Rocky Horror’s history. Sometimes the next part of a story isn’t so happy, but that doesn’t mean it’s not worth telling, whether it inspires those watching to get up and dance or not.